Stephen Sherman discusses some of the things that may or may not be given appropriate treatment in the new PBS documentary series to air this fall, covering American involvement in the former French colonies:

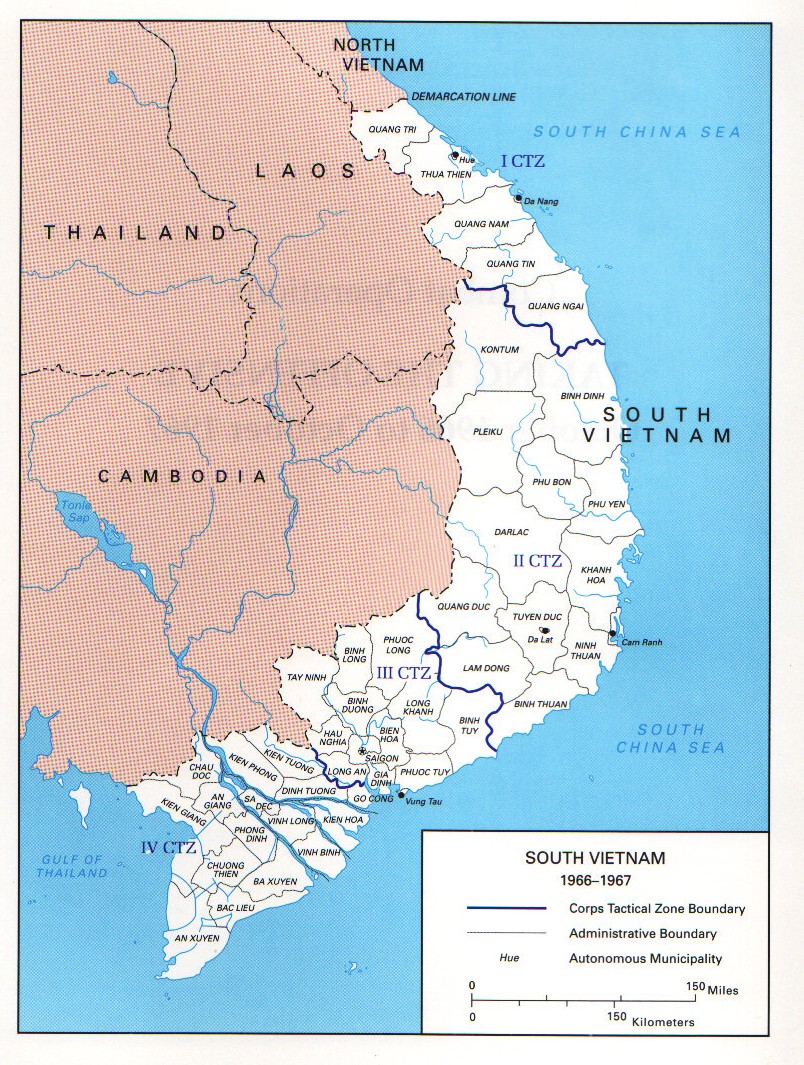

Indochina in 1954. Map prepared for the US Military Acadamy’s military atlas series. (Via Wikimedia).

Ken Burns correctly identifies the Vietnam War as being the point at which our society split into two diametrically opposed camps. He is also correct in identifying a need for us to discuss this aspect of our history in a civil and reflective manner. The problem is that the radical political and cultural divisions of that war have created alternate perceptions of reality, if not alternate universes of discourse. The myths and propaganda of each side make rational discourse based on intellectual honesty and goodwill difficult or impossible. The smoothly impressive visual story Burns will undoubtedly deliver will likely increase that difficulty. He has done many popular works in the past, some of which have been seriously criticized for inaccuracies and significant omissions, but we welcome the chance of a balanced treatment of the full history of that conflict. We can only wait and watch closely when it goes public.

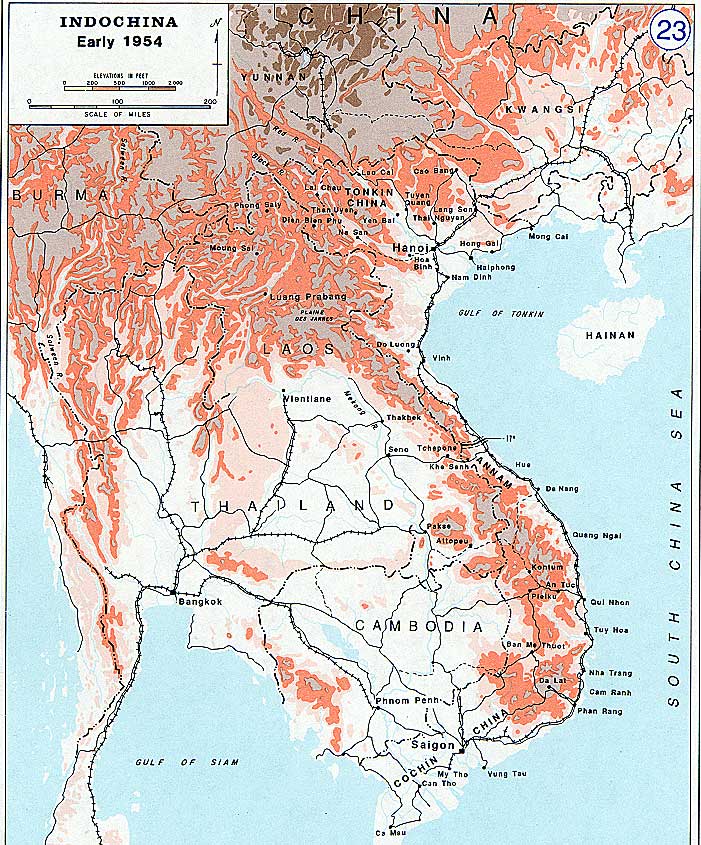

The term “Vietnam War” itself, although accepted in common parlance, would more accurately be called “The American Phase of the Second Indochina War” (1965 to 1973). The U.S. strategic objectives in Vietnam must also be accurately defined. There were two inter-related goals: 1) to counter the Soviet and Red Chinese strategy of fostering and supporting “Wars of National Liberation” (i.e., violent Communist takeovers) in third-world nations, and 2) to defend the government of the Republic of (South) Vietnam from the military aggression directed by its Communist neighbor, the Democratic Republic of (North) Vietnam.

Arguments offered by the so-called “anti-war” movement in the United States were predominantly derived from Communist propaganda. Most of them have been discredited by subsequent information, but they still influence the debate. They include the nonfactual claims that:

1) the war in South Vietnam was an indigenous civil war,

2) the U.S. effort in South Vietnam was a form of neo-colonialism, and

3) the real U.S. objective in South Vietnam was the economic exploitation of the region.

The antiwar movement was not at all monolithic. Supporters covered a wide range, from total pacifist Quakers at one end to passionate supporters of Communism at the other. There were many idealists in it who thought the war was unjust and our conduct of it objectionable, as well as students who were terrified of the draft, and some who just found it the cause of the day. But some of the primary figures leading the movement were not so much opposed to the war as they were in favor of Hanoi succeeding in the war it had started.

The key question is whether the U.S. opposition to Communism during the Cold War (1947 to 1989) was justifiable. The answer is that Communism (Marxism) on a national level is a utopian ideal that can function only with the enforcement of a police state (Leninism) or a genocidal criminal regime (Stalinism). It always requires an external enemy to justify the continuous hardships and repression of its population and always claims that its international duty is to spread Communism. When Ho Chi Minh established the Vietnam Communist Party in 1930, there was no intention of limiting its expansionist ambitions to Vietnam, and he subsequently changed the name to the Indochinese Communist Party at the request of the Comintern in Moscow.