The received wisdom about the transition from hunter-gatherer to agrarian societies is that clans or tribes stopped being nomadic in order to grow crops and secure their food supply more consistently … that growing grain for bread was one of the strongest underlying reasons for the change in lifestyle. That theory is being challenged by researchers who believe the real reason was to produce grains for brewing instead:

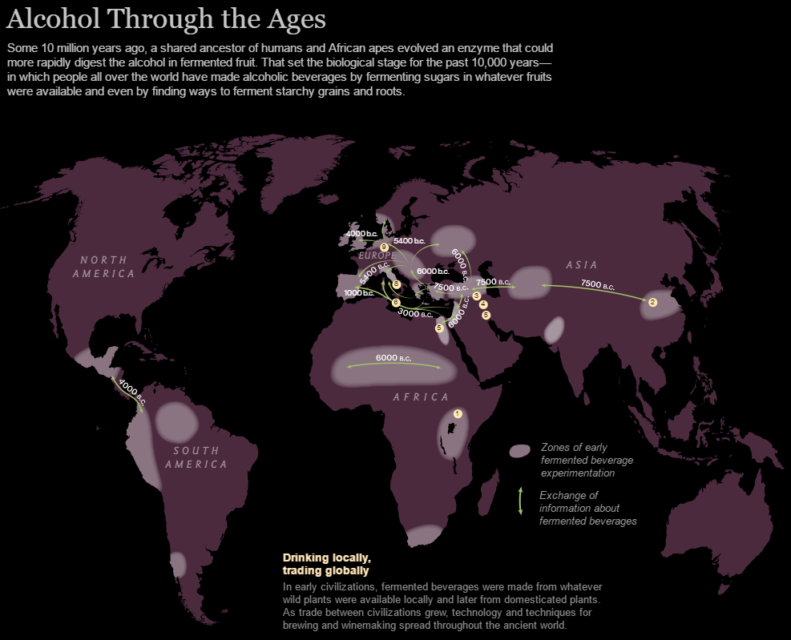

The story of humanity’s love affair with alcohol goes back to a time before farming — to a time before humans, in fact. Our taste for tipple may be a hardwired evolutionary trait that distinguishes us from most other animals.

The active ingredient common to all alcoholic beverages is made by yeasts: microscopic, single-celled organisms that eat sugar and excrete carbon dioxide and ethanol, the only potable alcohol. That’s a form of fermentation. Most modern makers of beer, wine, or sake use cultivated varieties of a single yeast genus called Saccharomyces (the most common is S. cerevisiae, from the Latin word for “beer,” cerevisia). But yeasts are diverse and ubiquitous, and they’ve likely been fermenting ripe wild fruit for about 120 million years, ever since the first fruits appeared on Earth.

From our modern point of view, ethanol has one very compelling property: It makes us feel good. Ethanol helps release serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins in the brain, chemicals that make us happy and less anxious.

To our fruit-eating primate ancestors swinging through the trees, however, the ethanol in rotting fruit would have had three other appealing characteristics. First, it has a strong, distinctive smell that makes the fruit easy to locate. Second, it’s easier to digest, allowing animals to get more of a commodity that was precious back then: calories. Third, its antiseptic qualities repel microbes that might sicken a primate. Millions of years ago one of them developed a taste for fruit that had fallen from the tree. “Our ape ancestors started eating fermented fruits on the forest floor, and that made all the difference,” says Nathaniel Dominy, a biological anthropologist at Dartmouth College. “We’re preadapted for consuming alcohol.”

[…]

Flash forward millions of years to a parched plateau in southeastern Turkey, not far from the Syrian border. Archaeologists there are exploring another momentous transition in human prehistory, and a tantalizing possibility: Did alcohol lubricate the Neolithic revolution? Did beer help persuade Stone Age hunter-gatherers to give up their nomadic ways, settle down, and begin to farm?

The ancient site, Göbekli Tepe, consists of circular and rectangular stone enclosures and mysterious T-shaped pillars that, at 11,600 years old, may be the world’s oldest known temples. Since the site was discovered two decades ago, it has upended the traditional idea that religion was a luxury made possible by settlement and farming. Instead the archaeologists excavating Göbekli Tepe think it was the other way around: Hunter-gatherers congregated here for religious ceremonies and were driven to settle down in order to worship more regularly.

H/T to Tamara Keel for the link.