Published on 2 Jan 2015

This video explores factors that shift the supply curve. How do technological innovations, input prices, taxes and subsidies, and other factors affect a firm’s costs and the price at which the firm is willing to sell a good? By answering these questions we have a better idea of how the supply curve will shift. This video walks you through examples and scenarios that illustrate this concept.

April 14, 2015

The Supply Curve Shifts

(Some) Corporations love (some) social causes

You’ll notice some corporations are quick to climb onboard certain social causes. Because reasons:

My absolute favorite example of corporations using social causes as cover for cost-cutting is in hotels. You have probably seen it — the little cards in the bathroom that say that you can help save the world by reusing your towels. This is freaking brilliant marketing. It looks all environmental and stuff, but in fact they are just asking your permission to save money by not doing laundry.

However, we may have a new contender for my favorite example of this. Via Instapundit, Reddit CEO Ellen Pao is banning salary negotiations to help women, or something:

Men negotiate harder than women do and sometimes women get penalized when they do negotiate,’ she said. ‘So as part of our recruiting process we don’t negotiate with candidates. We come up with an offer that we think is fair. If you want more equity, we’ll let you swap a little bit of your cash salary for equity, but we aren’t going to reward people who are better negotiators with more compensation.’

Like the towels in hotels are not washed to save the world, this is marketed as fairness to women, but note in fact that women don’t actually get anything. What the company gets is an excuse to make their salaries take-it-or-leave-it offers and helps the company draw the line against expensive negotiation that might increase their payroll costs.

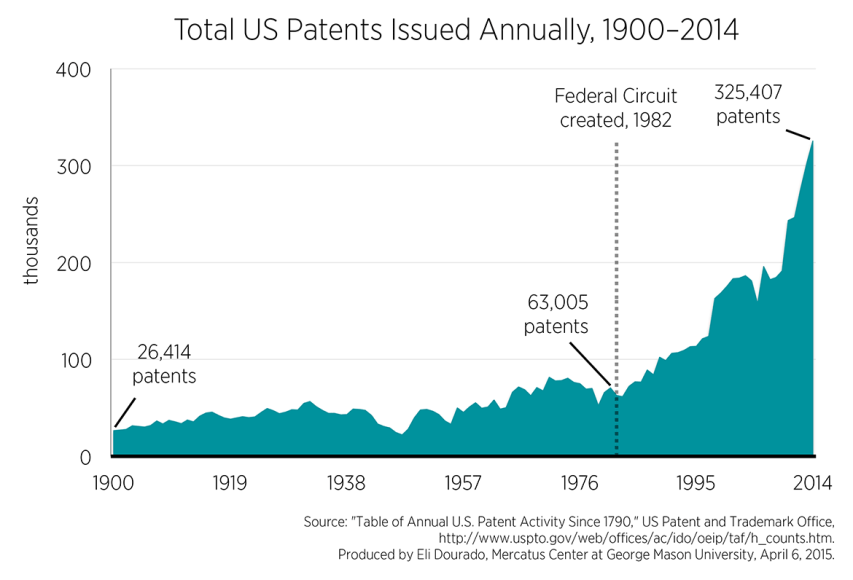

Patently ridiculous, in one image

H/T to Veronique de Rugy, who explains that much of the increase in “patents for trivial and non-original functions” can be traced back to the creation of one particular court.

Strategies of the Sri Lankan civil war

In The Diplomat, Peter Layton looks back at the strategies that eventually ended the twenty-five year civil war in Sri Lanka:

How to win a civil war in a globalized world where insurgents skillfully exploit offshore resources? With most conflicts now being such wars, this is a question many governments are trying to answer. Few succeed, with one major exception being Sri Lanka where, after 25 years of civil war the government decisively defeated the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and created a peace that appears lasting. This victory stands in stark contrast to the conflicts fought by well-funded Western forces in Iraq and Afghanistan over the last decade. How did Sri Lanka succeed against what many considered the most innovative and dangerous insurgency force in the world? Three main areas stand out.

First, the strategic objective needs to be appropriate to the enemy being fought. For the first 22 years of the civil war the government’s strategy was to bring the LTTE to the negotiating table using military means. Indeed, this was the advice foreign experts gave as the best and only option. In 2006, just before the start of the conflict’s final phase, retired Indian Lieutenant General AS Kalkat in 2006 declared, “There is no armed resolution to the conflict. The Sri Lanka Army cannot win the war against the Lankan Tamil insurgents.”

Indeed, the LTTE entered negotiations five times, but talks always collapsed, leaving a seemingly stronger LTTE even better placed to defeat government forces. In mid-2006, sensing victory was in its grasp, the LTTE deliberately ended the Norwegian-brokered ceasefire and initiated the so-called Eelam War IV. In response, the Sri Lankan government finally decided to change its strategic objective, from negotiating with the LTTE to annihilating it.

To succeed, a strategy needs to take into account the adversary. In this case it needed to be relevant to the nature of the LTTE insurgency. Over the first 22 years of the civil war, the strategies of successive Sri Lankan governments did not fulfill this criterion. Eventually, in late 2005 a new government was elected that choose a different strategic objective that matched the LTTE’s principal weaknesses while negating their strengths.

The LTTE’s principal problem was its finite manpower base. Only 12 percent of Sri Lanka’s population were Lankan Tamils and of these it was believed that only some 300,000 actively supported the LTTE. Moreover, the LTTE’s legitimacy as an organization was declining. By 2006, the LTTE relied on conscription – not volunteers – to fill its ranks and many of these were children. At the operational level some seeming strengths could also be turned against the LTTE, including its rigid command structure, a preference for fighting conventional land battles, and a deep reliance on international support.

QotD: Blaming France for causing the First World War

To begin with, any attempt to shift blame for World War I from Germany onto the French-Russian alliance has to deal with Germany’s responsibility for creating that alliance in the first place. If France wanted Alsace and Lorraine back, it was only because it had lost the territories in a war engineered by Germany. Karl Marx, in a moment of rare foresight, predicted that Germany’s decision to annex Alsace and Lorraine would end “by forcing France into the arms of Russia.” Similarly, it was Germany’s decision not to renew its alliance with Russia that led to increasing enmity between Russia and Austria, and to the creation of an anti-German alliance between Russia and France. And the German decision to rebuff British overtures in favor of a naval arms race (not to mention provoking the Agadir Crisis) pushed yet another potential ally into the enemy camp. Germany’s ability to lose friends and alienate people would continue during World War I itself, with such brilliant diplomatic maneuvers as the Zimmerman telegraph, unrestricted submarine warfare, and the decision to let Lenin back into Russia.

But leave all that aside. It’s certainly true that France wanted to get Alsace and Lorraine back from Germany, and that France knew the only hope it had of beating Germany in a war was with Russia as an ally. But this had been true for decades prior to 1914. Had France and Russian really wanted to start a war with the central powers, they had plenty of opportunities. But they didn’t. Clark himself concedes this, noting that “at no point did the French or the Russian strategists involved plan to launch a war of aggression against the central powers.”

What’s more, far from being an instigator, France was disengaged during much of the July Crisis. Attention in France during July 1914 was focused on a particularly lurid murder trial involving the wife of a prominent politician. During the key period of the Austrian ultimatum, both the French president and prime minister were stuck on a boat returning from St. Petersburg. And when leaders did finally arrive in Paris, their moves were not aggressive. The French prime minister cabled Russia on July 30 that it “should not immediately proceed to any measure which might offer Germany a pretext for a total or partial mobilization of her forces” and the French army itself was pulled back six miles from the German frontier.

Josiah Neeley, “Historical Revisionism Update: Yes, Germany (Mostly) Started World War I”, The Federalist, 2014-01-06