I thought we’d be done by now, but there’s still more historical ground to cover on what I think are the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six). The previous post examined the naval arms race between Britain and Germany. Today, we’re looking at the unhappy Russian experiences in the far East and the dangerous domestic situation it faced after the war.

Russia’s Oriental catastrophe

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 was a huge upset, as all the great powers expected Russia to crush the upstart Japanese and put them back “in their place”. Japan’s stunning naval and military successes at the Battle of the Yellow Sea, Tsushima and Port Arthur left Russia in a potentially disastrous situation, with utter undeniable defeat in the East and revolution brewing at home.

The war came about due to irreconcilable differences in the expansionary plans of the two empires: Russia wanted control of Manchuria and Japan wanted control of Korea, but neither side trusted the other enough to make negotiations work. Japan decided to initiate the conflict with a surprise attack on the Russian naval forces in Port Arthur (now known as the Lüshunkou District of Dalian in China’s Liaoning province). From that point onwards, Japan maintained the initiative, forcing Russia to react and interrupting Russian moves on land and at sea.

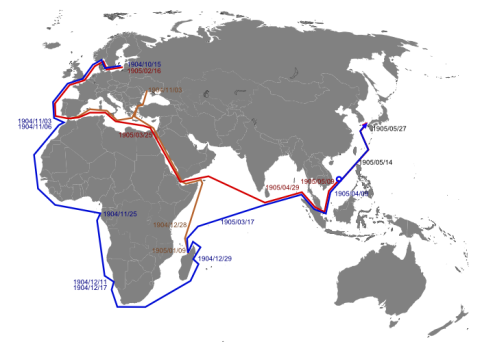

After the defeat of the original Russian fleet in the Pacific, the Baltic Fleet was re-tasked and set out to avenge the loss. The fleet’s luck was terrible to begin with, as shortly after passing between Sweden and Denmark and sailing out into the North Sea, lookouts on the Russian battleships spotted Japanese forces and the fleet opened fire. Twenty minutes, later the enemy was in tatters … unfortunately, the “enemy” were British fishing trawlers. Given the massive firepower of even pre-dreadnought ships, the casualties were surprisingly light: one trawler sunk, two dead, and many wounded. Not long afterward, a Russian ship in the fleet was mis-identified as a Japanese ship and nearly sunk by friendly fire. The nearest Japanese ship was still thousands of miles to the East.Despite nearly starting a war with the Royal Navy over the Dogger Bank incident (Britain and Japan had signed an alliance in 1902), Admiral Rozhdestvensky was unapologetic and insisted it was the trawlers’ fault and his ships were perfectly entitled to defend themselves from Japanese attackers. As a result of the Russian mistake, Britain refused to allow the fleet passage through the Suez Canal, forcing them to take the far longer trip around Africa instead. If ever a military expedition has had bad omens, the sortie of the Baltic Fleet — now renamed the Second Pacific Squadron for this mission — must be one of the best examples.

When the Russian and Japanese fleets met in the Tsushima Straits, Admiral Tōgō managed to “cross the T” of the Russians, allowing his ships to use their full broadside armament against only the forward-facing guns of the Russian ships. In the end, the Second Pacific Squadron lost all eleven battleships and over 4,000 men killed, another 5,900 captured, and 1,800 interned. Japanese losses were trivial in comparison: three torpedo boats sunk, 117 men killed and about 500 wounded.

There were no major subsequent battles, and Russia was forced to sign the Treaty of Portsmouth to end the war in September 1905. Despite the Tsar’s initial instructions to the Russian delegation, the Russians agreed to recognize Japan’s sphere of influence in Korea, withdraw their troops from Manchuria, and to give up their lease on Port Arthur and Talien. The reaction in both countries was similar: political unrest. Japanese public opinion was that they had been cheated of their full reward from the war, and the government fell in the aftermath. Russians were even more angry and the result was revolution.

The (first) Russian revolution

While the result of the Russo-Japanese war was the trigger for the 1905 Revolution, it was far from being the only grievance. Margaret MacMillan wrote in The War That Ended Peace:

In 1904 the Minister of the Interior, Vyacheslav Plehve, is reported to have said that Russia needed “a small victorious war” which would take the minds of the Russian masses off “political questions”.

The Russo-Japanese War showed the folly of that idea. In its early months Plehve himself was blown apart by a bomb; towards its end the newly formed Bolsheviks tried to seize Moscow. The war served to deepen and bring into sharp focus the existing unhappiness of many Russians with their own society and its rulers. As the many deficiencies, from command to supplies, of the Russian war effort became apparent, criticism grew, both of the government and, since the regime was a highly personalized one, of the Tsar himself. In St. Petersburg a cartoon showed the Tsar with his breeches down being beaten while he says, “Leave me alone. I am the autocrat!” Like the French Revolution, with which it had many similarities, the Russian Revolution of 1905 broke old taboos, including the reverence surrounding the country’s ruler. It seemed to officials in St. Petersburg a bad omen that the Empress had hung a portrait of Marie Antoinette, a gift from the French government, in her rooms.

In December 1904, a strike in St. Petersburg triggered sympathy strikes in other industries, leading to 80,000 workers and supporters protesting in the city. In January 1905, a mass march by the strikers to the Winter Palace was met with rifle fire from the defending troops. Casualty estimates range from 200 to over 1,000 on Bloody Sunday. The strikes and protests spread beyond St. Petersburg, to the point that the government was threatened. Eventually the Tsar was persuaded to offer concessions :

Under huge pressure from his own supporters, the Tsar reluctantly issued a manifesto in October promising a responsible legislature, the Duma, as well as civil rights.

As so often happens in revolutionary moments, the concessions only encouraged the opponents of the regime. It appeared to be close to collapsing with its officials confused and ineffective in the face of such widespread disorder. That winter a battalion from Nichlas’s own regiment, the Preobrazhensky Guards, which had been founded by Peter the Great, mutinied. A member of the Tsar’s court wrote in his diary: “This is it.” Fortunately for the regime, its most determined enemies were disunited and not yet ready to take power while moderate reformers were prepared to support it in the light of the Tsar’s promises. Using the army and police freely, the government managed to restore order. By the summer of 1906 the worst was over — for the time being. The regime still faced the dilemma, though, of how far it could let reforms go without fatally undermining its authority. It was a dilemma faced by the French government in 1789 or the Shah’s government in Iran in 1979. Refusing demands for reform and relying on repression creates enemies; giving way encourages them and brings more demands.

Russia’s economy did recover eventually, but the political solution was not strong enough to stand the strains of another war any time soon. In some ways, it’s hard to imagine what the Russian leaders who advised the Tsar were thinking as the Russians continued to stir the pot in the Balkans…