![]() My weekly Guild Wars 2 community round-up at GuildMag is now online. The current chapter of the Living Story is called The Dragon’s Reach, Part 1 … but for various reasons I haven’t actually tried any of the new content yet. I expect to get caught up this weekend. In addition, there’s the usual assortment of blog posts, videos, podcasts, and fan fiction from around the GW2 community.

My weekly Guild Wars 2 community round-up at GuildMag is now online. The current chapter of the Living Story is called The Dragon’s Reach, Part 1 … but for various reasons I haven’t actually tried any of the new content yet. I expect to get caught up this weekend. In addition, there’s the usual assortment of blog posts, videos, podcasts, and fan fiction from around the GW2 community.

August 1, 2014

This week in Guild Wars 2

Old and busted – “I cannae change the laws of physics”?

Call me an old fogey, but I’ve always believed in the law of conservation of momentum … yet a recent NASA finding — if it holds up — may bring me around:

Nasa is a major player in space science, so when a team from the agency this week presents evidence that “impossible” microwave thrusters seem to work, something strange is definitely going on. Either the results are completely wrong, or Nasa has confirmed a major breakthrough in space propulsion.

British scientist Roger Shawyer has been trying to interest people in his EmDrive for some years through his company SPR Ltd. Shawyer claims the EmDrive converts electric power into thrust, without the need for any propellant by bouncing microwaves around in a closed container. He has built a number of demonstration systems, but critics reject his relativity-based theory and insist that, according to the law of conservation of momentum, it cannot work.

[…]

“Test results indicate that the RF resonant cavity thruster design, which is unique as an electric propulsion device, is producing a force that is not attributable to any classical electromagnetic phenomenon and therefore is potentially demonstrating an interaction with the quantum vacuum virtual plasma.”

This last line implies that the drive may work by pushing against the ghostly cloud of particles and anti-particles that are constantly popping into being and disappearing again in empty space. But the Nasa team has avoided trying to explain its results in favour of simply reporting what it found: “This paper will not address the physics of the quantum vacuum plasma thruster, but instead will describe the test integration, test operations, and the results obtained from the test campaign.”

The drive’s inventor, Guido Fetta calls it the “Cannae Drive”, which he explains as a reference to the Battle of Cannae in which Hannibal decisively defeated a much stronger Roman army: you’re at your best when you are in a tight corner. However, it’s hard not to suspect that Star Trek‘s Engineer Scott — “I cannae change the laws of physics” — might also be an influence. (It was formerly known as the Q-Drive.)

The New York Times bravely challenges … a policy they’ve propagandized for a century

In Forbes, Jacob Sullum admits that the sudden change of heart by the New York Times made him stop and reconsider whether he’d been wrong all this time:

According to a recent poll by the Pew Research Center, 54 percent of American adults support marijuana legalization. That’s around 130 million people. It turns out that some of them are members of the New York Times editorial board, which on Sunday declared that “the federal government should repeal the ban on marijuana.”

Given its timing, the paper’s endorsement of legalization is more an indicator of public opinion than a brave stand aimed at changing it. Andrew Rosenthal, editorial page editor at the Times, told MSNBC’s Chris Hayes that the new position was not controversial among the paper’s 18 editorial writers and that when he raised the subject with the publisher, Arthur Sulzberger, “He said, ‘Fine.’ I think he’d probably been there before I was. I think I was there before we did it.” Better late than never, I guess, although I confess that seeing a New York Times editorial in favor of legalizing marijuana briefly made me wonder if I’ve been wrong about the issue all these years.

In their gratitude for the belated support of a venerable journalistic institution, antiprohibitionists should not overlook the extent to which the Times has aided and abetted the war on marijuana over the years. That shameful history provides a window on the origins of this bizarre crusade and a lesson in the hazards of failing to question authority.

[…]

In short, the Times first publicly toyed with the idea of marijuana legalization in 1972, but it did not get around to endorsing that policy until 42 years later. What happened in between? Jimmy Carter, a president who advocated decriminalization, was replaced in 1981 by Ronald Reagan, a president who ramped up the war on drugs despite his lip service to limited government. That crusade was supported by parents who were alarmed by record rates of adolescent pot smoking in the late 1970s. Gallup’s numbers indicate that support for legalizing marijuana, after rising from 12 percent in 1969 to 28 percent in 1978, dipped during the Reagan administration, hitting a low of 23 percent in 1985 before beginning a gradual ascent.

Legalization did get at least a couple of positive mentions on the New York Times editorial page during the 1980s. A 1982 essay actually advocated “regulation and taxation” as “a more sensible alternative” to decriminalization, arguing that “a prohibition so unenforceable and so widely flouted must give way to reality.” But that piece was attributed only to editorial writer Peter Passell, so it did not represent the paper’s official position. Four years later, an editorial that was mainly about drug testing asked, “Why not sharpen priorities by legalizing or at least decriminalizing marijuana?” Good question. Let’s think about it for a few decades.

Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One? (Part four of a series)

Over the last few days, I’ve posted some entries on the deep origins of the First World War (part one, part two, part three). We’re still sorting out the end of Otto von Bismarck’s grand diplomatic juggling act, and we’ve barely dug into the fascinating ethnic, religious, cultural, and linguistic goulash of the Balkans.

France searches for allies

After the disaster of the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second Empire, France was left (for the second time) alone and friendless on the European stage. Having painfully rebuilt from the end of the Napoleonic wars, France faced the need to do it all again, but now with a newly unified and powerful enemy literally on the Eastern frontier.

The overriding foreign policy objectives of the Third Republic were finding ways to counteract the German Reich … even if it meant cosying up to the most autocratic regime in Europe. With Bismarck off the scene, the French were able to further pursue a dialogue with the Tsar’s government that actually began with financial aid from Paris in 1888 leading eventually to a formal alliance in 1892. The loans were intended to allow Russia to improve existing East-West railways and to build new ones with the purpose of allowing Russian troops to be more quickly concentrated on the German-Russian and (less urgently) Austrian-Russian borders. Russia had the military manpower while France had the financial means and technological know-how — both parties drew benefits from the deal (but the French needed the Russians more than vice-versa).

In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan shows that the Russians were aware of the imbalance in the needs of the allies and resented the French attitude to them:

Although the French alliance had caused difficulties initially, Russian opinion had largely come around to seeing it as a good thing, a neat matching of Russian manpower with French money and technology. Of course, there were strains over the years. France tried to use its financial leverage over Russia to shape Russian military planning to meet French needs or to insist that Russia place its orders for new weapons with French firms. The Russians resented this “blackmail”, as they sometimes called it, which was demeaning to Russia as a great power. As Vladimir Kokovtsov, Russia’s Minister of Finance for much of the decade before 1914, complained: “Russia is not Turkey; our allies should not set us an ultimatum, we can get by without these direct demands.”

The French also put pressure on Russia to avoid confrontations with Britain, as French and British diplomats had started working toward some kind of understanding, and the French felt (with some justice) that the Russians might easily do damage to that process by some mild adventurism on a distant frontier with Britain’s colonies.

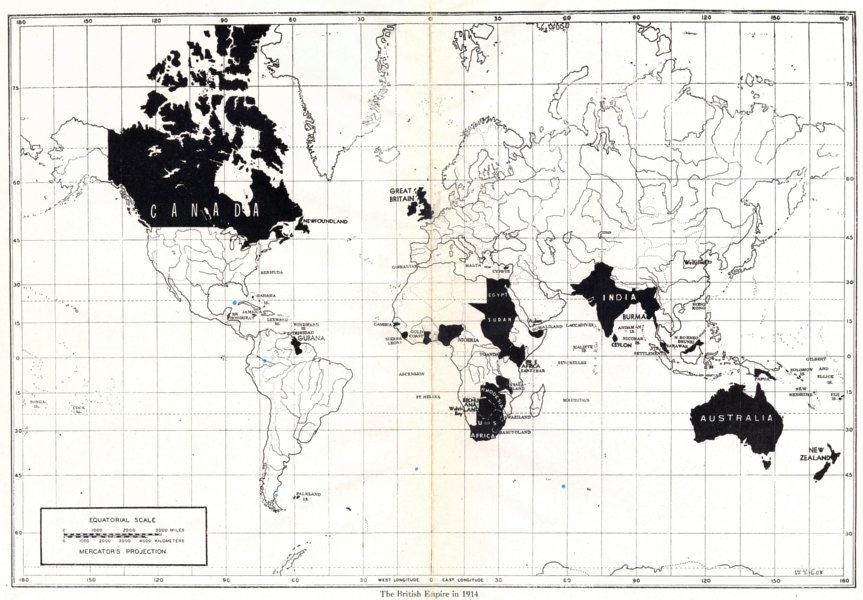

Britain’s global-scale worries

Britain’s lack of direct engagement during much of the period of the Concert of Europe was rational: British interests lay away from Europe, with the burgeoning colonies providing more than enough economic, diplomatic, and military activity for British tastes. From British Imperial viewpoints, the Germans were a mere distraction — it was the Russians who seemed to be threatening the Empire at every turn.

Margaret MacMillan writes that before the popular series of sensationalist novels by William Le Queux featured German invasions of Britain, his chosen villains were the Russians:

In Britain itself, public opinion was strongly anti-Russian. In popular literature, Russia was exotic and terrifying: the land of snow and golden domes, of wolves chasing sleighs through the dark forests, of Ivan the Terrible and Catherine the Great. Before he made Germany the enemy in his novels, the prolific William Le Queux used Russia. In his 1894 The Great War in England in 1897, Britain was invaded by a combined French and Russian force but the Russians were by far the more brutal. British homes were burned, innocent civilians shot and babies bayoneted. “The soldiers of the Tsar, savage and inhuman, showed no mercy to the weak and unprotected. They jeered and laughed at piteous appeal, and with fiendish brutality enjoyed the destruction which everywhere they wrought.”

Aside from the role of barbarous invaders in popular fiction, there were sufficient things to offend British consciences which added to this general dislike of the Russian state:

Radicals, liberals and socialists all had many reasons to hate the regime with its secret police, censorship, lack of basic human rights, its persecution of its opponents, its crushing of ethnic minorities and its appalling record of anti-Semitism. Imperialists on the other hand hated Russia because it was a rival to the British Empire. Britain could never come to an agreement with Russia in Asia, said Curzon, who had been Salisbury’s Under-secretary at the Foreign Office before he became Viceroy in India. Russia was bound to keep expanding as long as it could get away with it. In any case the “ingrained duplicity” of Russian diplomats made negotiations futile.

In the wake of the abortive 1905 revolution, it was easy to think of Russia as being weak and unstable, but as economic growth slowly returned, the government’s efforts to extend its control over far-flung recently acquired territories led to roads and railways being built … which Britain could hardly help but view as being at least partly military in nature:

It was one of the rare occasions on which [Curzon] agreed with the chief of the Indian general staff, Lord Kitchener, who was demanding more resources from London to deal with “the menacing advance of Russia towards our frontiers.” What particularly worried the British were the new Russian railways, either built or planned, which stretched down to the borders of Afghanistan and Persia and which now made it possible for the Russians to bring more force to bear. Although the term was not to be coined for another eighty years, the British were also becoming acutely aware of what Paul Kennedy called “imperial overstretch”. As the War Office said in 1907, the expanded Russian railway system would make the military burden of defending India and the empire so great that “short of recasting our whole military system, it will become a question of practical politics whether or not it is worth our while to retain India.”

More to follow over the next few days. This series of blog posts has certainly ballooned past what I originally thought would be required (and I’m skipping over masses and masses of stuff already). This just reinforces my earlier point that the situation was far more complex 100 years ago than we might think.

QotD: Going swimming at the beach

I notice that people always make gigantic arrangements for bathing when they are going anywhere near the water, but that they don’t bathe much when they are there.

Sea-side scene: It is the same when you go to the sea-side. I always determine — when thinking over the matter in London — that I’ll get up early every morning, and go and have a dip before breakfast, and I religiously pack up a pair of drawers and a bath towel. I always get red bathing drawers. I rather fancy myself in red drawers. They suit my complexion so. But when I get to the sea I don’t feel somehow that I want that early morning bathe nearly so much as I did when I was in town.

On the contrary, I feel more that I want to stop in bed till the last moment, and then come down and have my breakfast. Once or twice virtue has triumphed, and I have got out at six and half-dressed myself, and have taken my drawers and towel, and stumbled dismally off. But I haven’t enjoyed it. They seem to keep a specially cutting east wind, waiting for me, when I go to bathe in the early morning; and they pick out all the three-cornered stones, and put them on the top, and they sharpen up the rocks and cover the points over with a bit of sand so that I can’t see them, and they take the sea and put it two miles out, so that I have to huddle myself up in my arms and hop, shivering, through six inches of water. And when I do get to the sea, it is rough and quite insulting.

One huge wave catches me up and chucks me in a sitting posture, as hard as ever it can, down on to a rock which has been put there for me. And, before I’ve said “Oh! Ugh!” and found out what has gone, the wave comes back and carries me out to mid-ocean. I begin to strike out frantically for the shore, and wonder if I shall ever see home and friends again, and wish I’d been kinder to my little sister when a boy (when I was a boy, I mean). Just when I have given up all hope, a wave retires and leaves me sprawling like a star-fish on the sand, and I get up and look back and find that I’ve been swimming for my life in two feet of water. I hop back and dress, and crawl home, where I have to pretend I liked it.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the dog), 1889.