Yesterday, I posted the first part of this series. Today, I’m dragging you a lot further back in time than you probably expected, because it’s difficult to understand why Europe went to war in 1914 without knowing how and why the alliances were created. It’s not immediately clear why the two alliance blocks formed, as the interests of the various nations had converged and diverged several times over the preceding hundred years.

Let me take you back…

To start sorting out why the great powers of Europe went to war in what looks remarkably like a joint-suicide pact at the distance of a century, you need to go back another century in time. At the end of the Napoleonic wars, the great powers of Europe were Russia, Prussia, Austria, Britain, and (despite the outcome of Waterloo) France. Britain had come out of the war in by far the best economic shape, as the overseas empire was relatively untroubled by conflict with the other European powers (with one exception), and the Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful in the world. France was an economic and demographic disaster area, having lost so many young men to Napoleon’s recruiting sergeants and the bureaucratic demands of the state to subordinate so much of the economy to the support of the armies over more than two decades of war, recovery from war, and preparation for yet more war. In spite of that, France recovered quickly and soon was able to reclaim its “rightful” position as a great power.

Dateline: Vienna, 1814

The closest thing to a supranational organization two hundred years ago was the Concert of Europe (also known as the Congress System), which generally referred to the allied anti-Napoleonic powers. They met in Vienna in 1814 to settle issues arising from the end of Napoleon’s reign (interrupted briefly but dramatically when Napoleon escaped from exile and reclaimed his throne in 1815). It worked well enough, at least from the point of view of the conservative monarchies:

The age of the Concert is sometimes known as the Age of Metternich, due to the influence of the Austrian chancellor’s conservatism and the dominance of Austria within the German Confederation, or as the European Restoration, because of the reactionary efforts of the Congress of Vienna to restore Europe to its state before the French Revolution. It is known in German as the Pentarchie (pentarchy) and in Russian as the Vienna System (Венская система, Venskaya sistema).

The Concert was not a formal body in the sense of the League of Nations or the United Nations with permanent offices and staff, but it provided a framework within which the former anti-Bonapartist allies could work together and eventually included the restored French Bourbon monarchy (itself soon to be replaced by a different monarch, then a brief republic and then by Napoleon III’s Second Empire). Britain after 1818 became a peripheral player in the Concert, only becoming active when issues that directly touched British interests were being considered.

The Concert was weakened significantly by the 1848-49 revolutionary movements across Europe, and its usefulness faded as the interests of the great powers became more focused on national issues and less concerned with maintaining the long-standing balance of power.

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, but within a year, reactionary forces had regained control, and the revolutions collapsed.

[…]

The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more forced into exile. The only significant lasting reforms were the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the definitive end of the Capetian monarchy in France. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire, but did not reach Russia, Sweden, Great Britain, and most of southern Europe (Spain, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire).

The 1859 unification of Italy created new problems for Austria (not least the encouragement of agitation among ethnic and linguistic minorities within the empire), while the rise of Prussia usurped the traditional place of Austria as the pre-eminent Germanic power (the Austro-Prussian War). The 1870-1 Franco-Prussian War destroyed Napoleon III’s Second Empire and allowed the King of Prussia to become the Emperor (Kaiser) of a unified German state.

Russia’s search for a warm water port

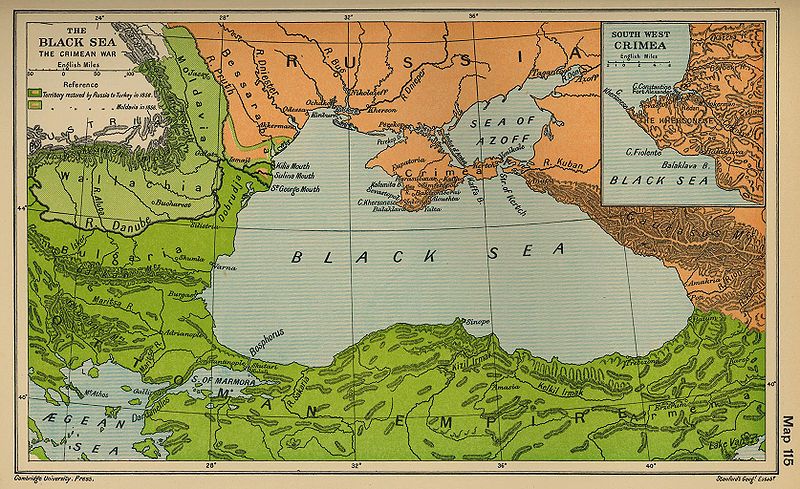

Russia’s not-so-secret desire to capture or control Constantinople and the access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean was one of the political and military constants of the nineteenth century. The Ottoman Empire was the “sick man of Europe”, and few expected it to last much longer (yet it took a world war to finally topple it). The other great powers, however, were not keen to see Russia expand beyond its already extensive borders, so the Ottomans were propped up where necessary. The unlikely pairing of British and French interests in this regard led to the 1853-6 Crimean War where the two former enemies allied with the Ottomans and the Kingdom of Sardinia to keep the Russians from expanding into Ottoman territory, and to de-militarize the Black Sea.

The Black Sea in 1856 with the territorial adjustments of the Congress of Paris marked (via Wikipedia)

Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck talks with the captive Napoleon III after the Battle of Sedan in 1870.

In the wake of Napoleon III’s fall, France declared that they were no longer willing to oppose the re-introduction of Russian forces on and around the Black Sea. Britain did not feel it could enforce the terms of the 1856 treaty unaided, so Russia happily embarked on building a new Black Sea fleet and reconstructing Sebastopol as a fortified fleet base.

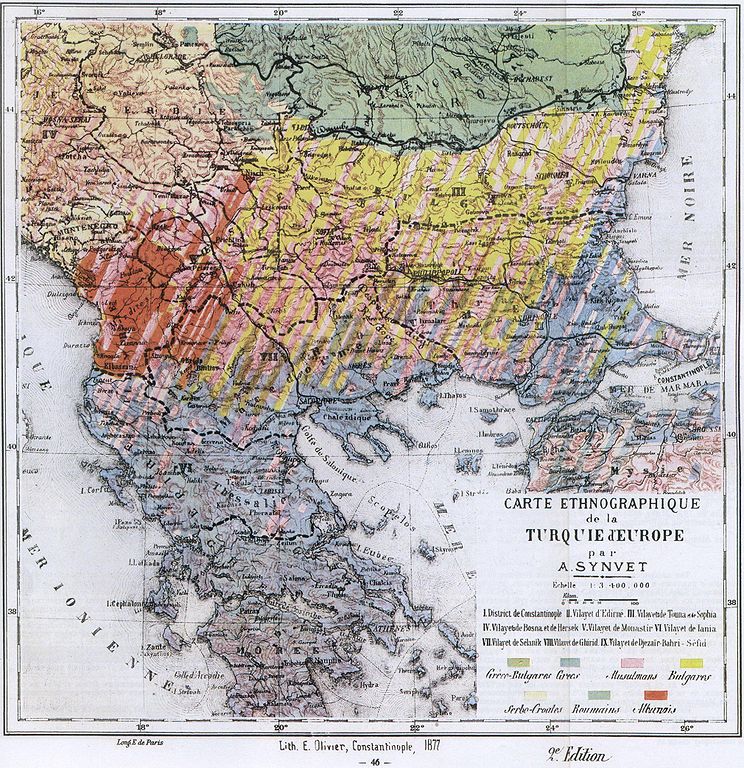

Twenty years after the Crimean War, the Russians found more success against the Ottomans, driving them out of almost all of their remaining European holdings and establishing independent or quasi-independent states including Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania, with at least some affiliation with the Russians. A British naval squadron was dispatched to ensure the Russians did not capture Constantinople, and the Russians accepted an Ottoman truce offer, followed eventually by the Treaty of San Stefano to end the war. The terms of the treaty were later reworked at the Congress of Berlin.

Other territorial changes resulting from the war was the restoration of the regions of Thrace and Macedonia to Ottoman control, the acquisition by Russia of new territories in the Caucasus and on the Romanian border, the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia, Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar (but not yet annexed to the empire), and British possession of Cyprus. The new states and provinces addressed a few of the ethnic, religious, and linguistic issues, but left many more either no better or worse than before:

An ethnographic map of the Balkans published in Carte Ethnographique de la Turquie d’Europe par A. Synvet, Lith. E Olivier, Constantinople 1877. (via Wikipedia)

The end of the second post and we’re still in the 1870s … more to come over the next few days.