This page started out as a set of blog posts in mid-2014, where I attempted to outline some of the most significant causes of the First World War. Two books in particular sparked my desire to do this:

The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark and The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 by Margaret MacMillan

While I didn’t draw exclusively from these works, I likely wouldn’t have put together the series of blog posts if I hadn’t read these two in relatively close succession to one another. I have made minor changes to some of the posts as they were originally published, and added material past the point of the final post to attempt to complete the story … as much as such a vast and complex story could be said to be “complete”.

- Part One: Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One?

- Part Two: Let me take you back…

- Part Three: Bismarck’s master class in realpolitik

- Part Four: France diplomatically isolated

- Part Five: Austria becomes Austria-Hungary

- Part Six: The Anglo-German naval race, Jackie Fisher, and HMS Dreadnought

- Part Seven: War with Japan, revolution at home: Russia’s self-inflicted miseries

- Part Eight: Italian Adventures in North Africa and the First Balkan War

- Part Nine: The Second Balkan War – the thieves fall out

- Part Ten: The Entente Cordiale, Moroccan crises, and the influence of public opinion

- Part Eleven: The Bosnian crisis of 1908

- Part Twelve: Serbia from independence to June, 1914

- Part Thirteen: The black act of the Black Hand: Assassinations in Sarajevo

Part One: Who is to blame for the outbreak of World War One?

It’s an easy question to ask, but a very hard one to answer. Traditionally, most people would answer “Germany”, with greater or lesser intensity as the years have passed (for example, here’s Boris Johnson making this particular case). More realistically, you might say Germany, Serbia, Austria, and Russia. Or just Serbia. Or just Russia. Or Britain (according to Niall Ferguson). Or France. Or the inflexible railway timetables for mobilization (Barbara Tuchman and others). Lots of candidates, none of whom can be clearly identified as the prime villain, because you can’t look at the situation in Europe in 1914 as anything other than complexity compounded.

There have been so many books written about the origins of the First World War because the origins are many, diverse, interconnected, and hard to weigh against one another in any rational fashion. The assassinations in Sarajevo turned out to be the triggering event, but the war could easily have broken out at any of several other potential flash points in the preceding decade — and even then, war could still have been prevented from breaking out in the summer of 1914. In some ways, it’s surprising that the alternative history folks haven’t been more active in exploring that era: the possibilities are quite fascinating (on second thought, having put this lengthy summary together, the degree of confusion may account for the novelists wisely avoiding the topic after all).

Although many authors refer to the various monarchs as active participants in the diplomatic and political spheres, this is not always an accurate way to consider their roles. The Tsar enjoyed the equivalent of a presidential veto and could start or stop government activity with a word … but most matters, even high-level military and diplomatic issues, would only come to his attention quite late in the process. This meant the Tsar might want to change his government’s course but because the situation was already well advanced, the costs to do so might well be insurmountable. As Tsar Nicholas I is reported to have said, “I don’t rule Russia, ten thousand clerks do.”

Tsar Nicholas II was perhaps the worst-equipped of all the leaders of Europe for the task facing him, emotionally and intellectually (and he was aware of his weaknesses). Even Kaiser Wilhelm, who was well-known for his quixotic interference in military and diplomatic matters, was not the sole autocrat of German policy. The chancellor and the foreign secretary could (and did) overrule the Kaiser’s whims on many occasions. On the other hand, King George V was the least directly involved of all the rulers in the actions of his empire, but his public stance may have been somewhat at variance with his private communications with crown ministers (for example, this recent article in the Telegraph claims that the King pushed Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, to “find a reason” to declare war on Germany).

A common misconception of the state of Europe in early 1914 was that the preceding century had been a golden age, peaceful and calm (think of all the discussions of the idyllic Edwardian era when contrasted with the chaos and disorder of 1914-1945 and beyond). Europe was only peaceful between 1815 and 1914 by contrast with previous centuries … there were many wars and the map of Europe was redrawn several times in that century. As Christopher Clark wrote:

Though the debate on this subject is now nearly a century old, there is no reason to believe that it has run its course.

But if the debate is old, the subject is still fresh — in fact it is fresher and more relevant now than it was twenty or thirty years ago. The changes in our own world have altered our perspective on the events of 1914. In the 1960s-80s, a kind of period charm accumulated in popular awareness around the events of 1914. It was easy to imagine the disaster of Europe’s ‘last summer’ as an Edwardian costume drama. The effete rituals and gaudy uniforms, the ‘ornamentalism’ of a world still largely organized around hereditary monarchy had a distancing effect on present-day recollection. They seemed to signal that the protagonists were people from another, vanished world. The presumption stealthily asserted itself that if the actors’ hats had gaudy green ostrich feathers on them, then their thoughts and motivations probably did too.

Margaret MacMillan shows how easily the calculations could go so wrong, so easily:

As we try to make sense of the events of the summer of 1914, we must put ourselves in the shoes of those who lived a century ago before we rush to lay blame. We cannot now ask the decision-makers what they were thinking about as they took those steps along that path to destruction, but we can get a pretty good idea from the records of that time and the memoirs written later. One thing that becomes clear is that those who made the choices had very much in mind previous crises and earlier moments when decisions were made or avoided.

Russia’s leaders, for example, had never forgotten or forgiven Austria-Hungary’s annexations of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908. Moreover, Russia had failed to back its protégé Serbia when it confronted Austria-Hungary then and again in the Balkan wars in 1912-13. Now Austria-Hungary was threatening to destroy Serbia. What would it mean for Russia and its prestige if it stood by yet again and did nothing? Germany had not fully backed its ally Austria-Hungary in those earlier confrontations; if it did nothing this time, would it lose its only sure ally? The fact that earlier and quite serious crises among the powers, over colonies or in the Balkans, had been settled peacefully added another factor to the calculations of 1914. The threat of war had been used but in the end pressures had been brought to bear by third parties, concessions had been made, and conferences had been summoned, with success, to sort out dangerous issues. Brinksmanship had paid off.

Part Two: Let me take you back…

Any attempt to explain why Europe went to war in 1914 requires going back a long way to identify the events which turned out to be important in the lead-up to the outbreak of war. In many cases, you need only go back a decade or two to find the trigger points that made a given war more likely, but in the case of WW1, I’m dragging you a lot further back in time than you probably expected, because it’s difficult to understand why Europe went to war in 1914 without knowing how and why the alliances were created. It’s not immediately clear why the two alliance blocks formed, as the interests of the various nations had converged and diverged several times over the preceding hundred years.

To start sorting out why the great powers of Europe went to war in what looks remarkably like a joint-suicide pact at the distance of a century, you need to go back another century in time. At the end of the Napoleonic wars, the great powers of Europe were Russia, Prussia, Austria, Britain, and (despite the outcome of Waterloo) France. Britain had come out of the war in by far the best economic shape, as the overseas empire was relatively untroubled by conflict with the other European powers (with one exception), and the Royal Navy was the largest and most powerful in the world. France was an economic and demographic disaster area, having lost so many young men to Napoleon’s recruiting sergeants and the bureaucratic demands of the state to subordinate so much of the economy to the support of the armies over more than two decades of war, recovery from war, and preparation for yet more war. In spite of that, France recovered quickly and soon was able to reclaim its “rightful” position as a great power.

Dateline: Vienna, 1814

The closest thing to a supranational organization two hundred years ago was the Concert of Europe (also known as the Congress System), which generally referred to the allied anti-Napoleonic powers. They met in Vienna in 1814 to settle issues arising from the end of Napoleon’s reign (interrupted briefly but dramatically when Napoleon escaped from exile and reclaimed his throne in 1815). It worked well enough, at least from the point of view of the conservative monarchies:

The age of the Concert is sometimes known as the Age of Metternich, due to the influence of the Austrian chancellor’s conservatism and the dominance of Austria within the German Confederation, or as the European Restoration, because of the reactionary efforts of the Congress of Vienna to restore Europe to its state before the French Revolution. It is known in German as the Pentarchie (pentarchy) and in Russian as the Vienna System (Венская система, Venskaya sistema).

The Concert was not a formal body in the sense of the League of Nations or the United Nations with permanent offices and staff, but it provided a framework within which the former anti-Bonapartist allies could work together and eventually included the restored French Bourbon monarchy (itself soon to be replaced by a different monarch, then a brief republic and then by Napoleon III’s Second Empire). Britain after 1818 became a peripheral player in the Concert, only becoming active when issues that directly touched British interests were being considered.

The Concert was weakened significantly by the 1848-49 revolutionary movements across Europe, and its usefulness faded as the interests of the great powers became more focused on national issues and less concerned with maintaining the long-standing balance of power.

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history, but within a year, reactionary forces had regained control, and the revolutions collapsed.

[…]

The uprisings were led by shaky ad hoc coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more forced into exile. The only significant lasting reforms were the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the definitive end of the Capetian monarchy in France. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Italy, and the Austrian Empire, but did not reach Russia, Sweden, Great Britain, and most of southern Europe (Spain, Serbia, Greece, Montenegro, Portugal, the Ottoman Empire).

The 1859 unification of Italy created new problems for Austria (not least the encouragement of agitation among ethnic and linguistic minorities within the empire), while the rise of Prussia usurped the traditional place of Austria as the pre-eminent Germanic power (the Austro-Prussian War). The 1870-1 Franco-Prussian War destroyed Napoleon III’s Second Empire and allowed the King of Prussia to become the Emperor (Kaiser) of a unified German state.

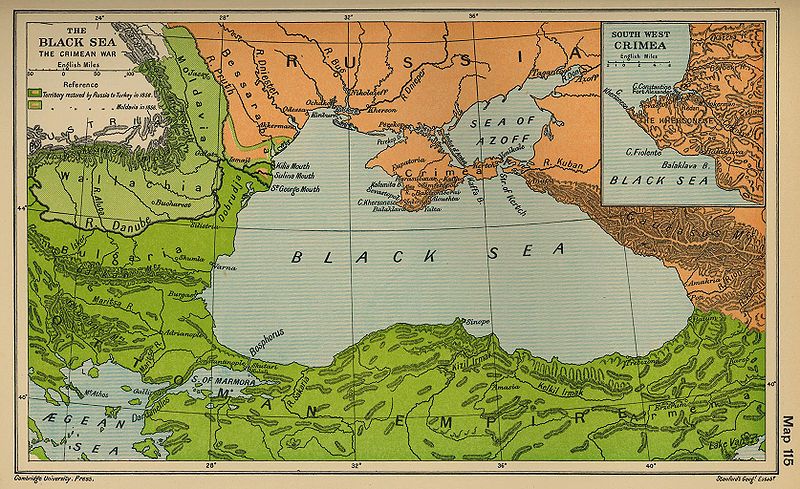

Russia’s search for a warm water port

Russia’s not-so-secret desire to capture or control Constantinople and the access from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean was one of the political and military constants of the nineteenth century. The Ottoman Empire was the “sick man of Europe”, and few expected it to last much longer (yet it took a world war to finally topple it). The other great powers, however, were not keen to see Russia expand beyond its already extensive borders, so the Ottomans were propped up where necessary. The unlikely pairing of British and French interests in this regard led to the 1853-6 Crimean War where the two former enemies allied with the Ottomans and the Kingdom of Sardinia to keep the Russians from expanding into Ottoman territory, and to de-militarize the Black Sea.

The Black Sea in 1856 with the territorial adjustments of the Congress of Paris marked (via Wikipedia)

Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck talks with the captive Napoleon III after the Battle of Sedan in 1870.

In the wake of Napoleon III’s fall, France declared that they were no longer willing to oppose the re-introduction of Russian forces on and around the Black Sea. Britain did not feel it could enforce the terms of the 1856 treaty unaided, so Russia happily embarked on building a new Black Sea fleet and reconstructing Sebastopol as a fortified fleet base.

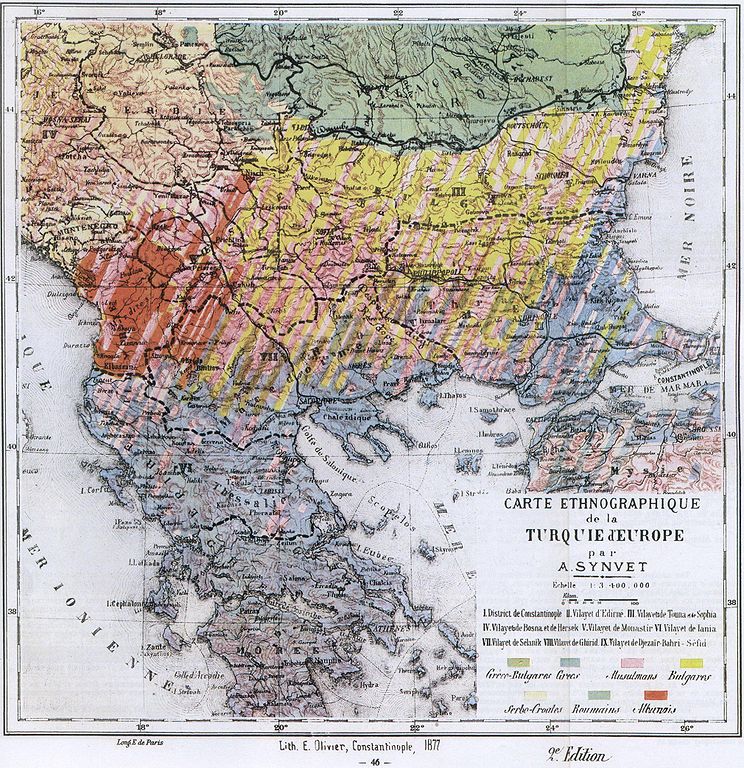

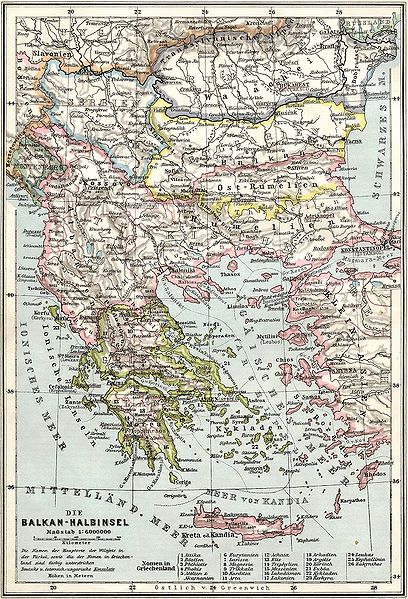

Twenty years after the Crimean War, the Russians found more success against the Ottomans, driving them out of almost all of their remaining European holdings and establishing independent or quasi-independent states including Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania, with at least some affiliation with the Russians. A British naval squadron was dispatched to ensure the Russians did not capture Constantinople, and the Russians accepted an Ottoman truce offer, followed eventually by the Treaty of San Stefano to end the war. The terms of the treaty were later reworked at the Congress of Berlin.

Other territorial changes resulting from the war was the restoration of the regions of Thrace and Macedonia to Ottoman control, the acquisition by Russia of new territories in the Caucasus and on the Romanian border, the Austro-Hungarian occupation of Bosnia, Herzegovina and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar (but not yet annexed to the empire), and British possession of Cyprus. The new states and provinces addressed a few of the ethnic, religious, and linguistic issues, but left many more either no better or worse than before:

An ethnographic map of the Balkans published in Carte Ethnographique de la Turquie d’Europe par A. Synvet, Lith. E Olivier, Constantinople 1877. (via Wikipedia)

Part Three: Bismarck’s master class in realpolitik

We’re just now getting to the point where the plots start twisting around one another like amorous snakes … this gets somewhat confusing from this point onwards (assuming you’re not already confused, that is).

Otto von Bismarck looms large in the story of the origins of the First World War, although he died several years before it broke out: he was the pre-eminent architect of the German Reich, and a brilliant (and ruthless) diplomatic engineer. Despite a common belief that Bismarck as a warmonger, Eric Hobsbawm wrote that Bismarck “remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, devot[ing] himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers” (The Age of Empire: 1875-1914).

While Bismarck became Chancellor of the new Reich in 1871, he had already held a series of important and powerful posts in the Prussian government, including Minister President of Prussia and Foreign Minister from 1861. In 1862, he made his long-range intentions quite plain in a speech to the Budget Committee:

Prussia must concentrate and maintain its power for the favorable moment which has already slipped by several times. Prussia’s boundaries according to the Vienna treaties are not favorable to a healthy state life. The great questions of the time will not be resolved by speeches and majority decisions — that was the great mistake of 1848 and 1849 — but by iron and blood.

In his long and impressive political career, he guided the creation of the unified German state while fending off the political demands of the liberals and socialists by conceding just enough to socialist pet causes to keep them working within the system (state pensions, for example, were a Bismarckian innovation calculated to just barely satisfy the left, but not to cost the state much if any actual revenue due to the high retirement age it set). He was emphatically not a fan of democracy: at one point, he finagled a “legal” way for the Prussian government’s revenues to continue for four years without a hint of democratic interference from the squabbling politicians in the Reichstag.

The editors of Bismarck’s Wikipedia entry seem to think he was first and foremost a benefactor to the working class, but I think they’re projecting — Reichskanzler Prince Otto von Bismarck was never particularly concerned with the welfare of the poor, except where that welfare contributed to the construction of a greater German empire. If that meant pandering to the Socialists, he’d pander with the best of them:

Bismarck implemented the world’s first welfare state in the 1880s. He worked closely with large industry and aimed to stimulate German economic growth by giving workers greater security. A secondary concern was trumping the Socialists, who had no welfare proposals of their own and opposed Bismarck’s. Bismarck especially listened to Hermann Wagener and Theodor Lohmann, advisers who persuaded him to give workers a corporate status in the legal and political structures of the new German state.

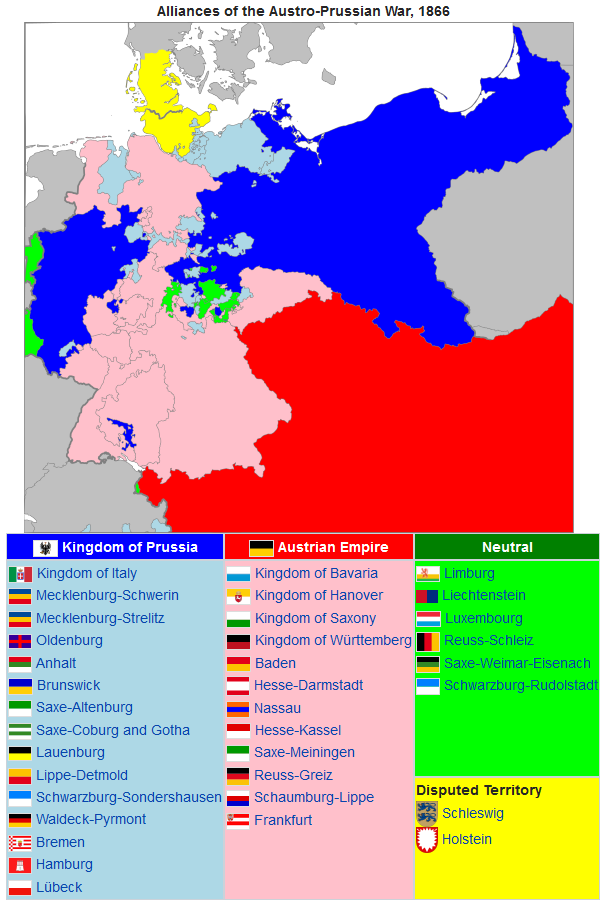

The wars he did fight were each calculated to advance the cause of German unification … under Prussian guidance and control, of course. Denmark lost the provinces of Schleswig (to Prussia) and Holstein (to Austria) in 1864, then Austria in turn lost Holstein (to Prussia) and Lombardy-Venetia (to Italy) two years later. His public moment of triumph was the proclamation of Wilhelm I as Emperor of Germany:

The proclamation of Prussian King Wilhelm I as German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles (Bismarck is at centre-right in the white uniform), by Anton von Werner. This version was commissioned by the Prussian royal family for chancellor Bismarck’s 70th birthday. (via Wikipedia)

Bismarck was not a fan of colonial adventures — he believed they were a distraction from more important issues in Europe and that the cost to obtain and run them was greater than the benefits derived from having them (and in hindsight, it’s hard to say he was wrong). Despite that, he allowed some colonies to be accumulated as game pieces to further his own priorities domestically. One of the European policies Bismarck implemented to great effect was the diplomatic isolation of France — on the quite reasonable basis that the French would take revenge on Germany for the humiliation of 1870 if they felt powerful enough to try it. The French Third Republic, which succeeded the Second Empire, was left without allies (and more galling: without the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine), due to Bismarck’s diligent efforts to bind the other great powers in alliances with one another and Bismarck managed to keep the French in that vulnerable position for the rest of his time in office.

Bismarck’s attempted solution to the Austro-Russian tensions in the Balkans was the Dreikaiserbund (The League of the Three Emperors) in 1873. This “meeting of the minds” was intended to dampen the risk of conflict by giving the Austrians a free hand in the Western area of the Balkans and the Russians a free hand in the East. The plan didn’t work as well as Bismarck had hoped, and the league was dissolved in 1887, as both of the other signatories felt too hampered by the terms of the agreement for too little benefit in return.

Bismarck’s next move was to create the Dual Alliance between Germany and Austria. The alliance was ostensibly defensive in nature, calling for each party to aid the other in the case of an attack by a third country (if the attacker was Russia, the alliance called for both parties to declare war, if it was another country — France — the non-attacked party was to remain neutral). In 1882, the Italians were added to the arrangement, but the terms of the Triple Alliance were not as defensive: requiring the other parties to actively assist an allied nation that was attacked, not just to remain neutral. Italy negotiated one clause in the agreement to ensure that they didn’t have to fight against Britain (which they activated in 1914).

The Turkish Straits (Bosporus Strait highlighted in red, and the Dardanelles Strait in yellow) (via Wikipedia)

In a speech to the Reichstag in 1888, Bismarck predicted the bloody outcome if a localized Balkan War were to trigger a continental one (from Emil Ludwig’s 1927 work, Wilhelm Hohenzollern: The last of the Kaisers):

He warned of the imminent possibility that Germany will have to fight on two fronts; he spoke of the desire for peace; then he set forth the Balkan case for war and demonstrates its futility: “Bulgaria, that little country between the Danube and the Balkans, is far from being an object of adequate importance … for which to plunge Europe from Moscow to the Pyrenees, and from the North Sea to Palermo, into a war whose issue no man can foresee. At the end of the conflict we should scarcely know why we had fought.”

Dropping the Pilot, a caricature by Sir John Tenniel (1820-1914), first published in the British magazine Punch, March 1890. (via Wikipedia)

One of the first critical pieces of diplomatic plumbing to go was the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia: the Russian government asked to renew the agreement, but Chancellor Caprivi (Bismarck’s successor) and Kaiser Wilhelm II thought they could do better by working the personal relationship between Wilhelm and Tsar Alexander III (and later, his “dear cousin Nicky” — Tsar Nicholas II). This worked so well that the French and Russian governments were already extending tentative diplomatic feelers toward one another by 1891.

Willliam L. Langer wrote of the end of Bismarck’s career:

Whatever else may be said of the intricate alliance system evolved by the German Chancellor, it must be admitted that it worked and that it tided Europe over a period of several critical years without a rupture. … there was, as Bismarck himself said, a premium upon the maintenance of peace.

[…]

His had been a great career, beginning with three wars in eight years and ending with a period of 20 years during which he worked for the peace of Europe, despite countless opportunities to embark on further enterprises with more than even chance of success. … No other statesman of his standing had ever before shown the same great moderation and sound political sense of the possible and desirable. … Bismarck at least deserves full credit for having steered European politics through this dangerous transitional period without serious conflict between the great powers.”

Part Four: France diplomatically isolated

After the disaster of the Franco-Prussian War and the collapse of the Second Empire, France was left (for the second time in a few generations) alone and friendless on the European stage. Having painfully rebuilt from the end of the Napoleonic wars, France faced the need to do it all again, but now with a newly unified and powerful enemy literally on the Eastern frontier.

The overriding foreign policy objectives of the Third Republic were finding ways to counteract the German Reich … even if it meant cosying up to the most autocratic regime in Europe. With Bismarck off the scene, the French were able to further pursue a dialogue with the Tsar’s government that actually began with financial aid from Paris in 1888 leading eventually to a formal alliance in 1892. The loans were intended to allow Russia to improve existing East-West railways and to build new ones with the purpose of allowing Russian troops to be more quickly concentrated on the German-Russian and (less urgently) Austrian-Russian borders. Russia had the military manpower while France had the financial means and technological know-how — both parties drew benefits from the deal (but the French needed the Russians more than vice-versa).

In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan shows that the Russians were aware of the imbalance in the needs of the allies and resented the French attitude to them:

Although the French alliance had caused difficulties initially, Russian opinion had largely come around to seeing it as a good thing, a neat matching of Russian manpower with French money and technology. Of course, there were strains over the years. France tried to use its financial leverage over Russia to shape Russian military planning to meet French needs or to insist that Russia place its orders for new weapons with French firms. The Russians resented this “blackmail”, as they sometimes called it, which was demeaning to Russia as a great power. As Vladimir Kokovtsov, Russia’s Minister of Finance for much of the decade before 1914, complained: “Russia is not Turkey; our allies should not set us an ultimatum, we can get by without these direct demands.”

The French also put pressure on Russia to avoid confrontations with Britain, as French and British diplomats had started working toward some kind of understanding, and the French felt (with some justice) that the Russians might easily do damage to that process by some mild adventurism on a distant frontier with Britain’s colonies.

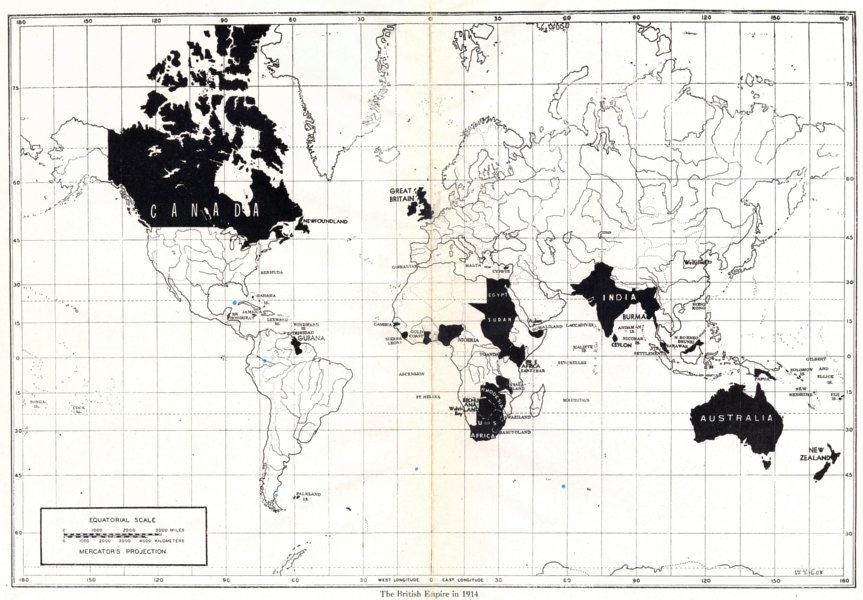

Britain’s global-scale worries

Britain’s lack of direct engagement during much of the period of the Concert of Europe was rational: British interests lay away from Europe, with the burgeoning colonies providing more than enough economic, diplomatic, and military activity for British tastes. From British Imperial viewpoints, the Germans were a mere distraction — it was the Russians who seemed to be threatening the Empire at every turn.

Margaret MacMillan writes that before the popular series of sensationalist novels by William Le Queux featured German invasions of Britain, his chosen villains were the Russians:

In Britain itself, public opinion was strongly anti-Russian. In popular literature, Russia was exotic and terrifying: the land of snow and golden domes, of wolves chasing sleighs through the dark forests, of Ivan the Terrible and Catherine the Great. Before he made Germany the enemy in his novels, the prolific William Le Queux used Russia. In his 1894 The Great War in England in 1897, Britain was invaded by a combined French and Russian force but the Russians were by far the more brutal. British homes were burned, innocent civilians shot and babies bayoneted. “The soldiers of the Tsar, savage and inhuman, showed no mercy to the weak and unprotected. They jeered and laughed at piteous appeal, and with fiendish brutality enjoyed the destruction which everywhere they wrought.”

Aside from the role of barbarous invaders in popular fiction, there were sufficient things to offend British consciences which added to this general dislike of the Russian state:

Radicals, liberals and socialists all had many reasons to hate the regime with its secret police, censorship, lack of basic human rights, its persecution of its opponents, its crushing of ethnic minorities and its appalling record of anti-Semitism. Imperialists on the other hand hated Russia because it was a rival to the British Empire. Britain could never come to an agreement with Russia in Asia, said Curzon, who had been Salisbury’s Under-secretary at the Foreign Office before he became Viceroy in India. Russia was bound to keep expanding as long as it could get away with it. In any case the “ingrained duplicity” of Russian diplomats made negotiations futile.

In the wake of the abortive 1905 revolution, it was easy to think of Russia as being weak and unstable, but as economic growth slowly returned, the government’s efforts to extend its control over far-flung recently acquired territories led to roads and railways being built … which Britain could hardly help but view as being at least partly military in nature:

It was one of the rare occasions on which [Curzon] agreed with the chief of the Indian general staff, Lord Kitchener, who was demanding more resources from London to deal with “the menacing advance of Russia towards our frontiers.” What particularly worried the British were the new Russian railways, either built or planned, which stretched down to the borders of Afghanistan and Persia and which now made it possible for the Russians to bring more force to bear. Although the term was not to be coined for another eighty years, the British were also becoming acutely aware of what Paul Kennedy called “imperial overstretch”. As the War Office said in 1907, the expanded Russian railway system would make the military burden of defending India and the empire so great that “short of recasting our whole military system, it will become a question of practical politics whether or not it is worth our while to retain India.”

Part Five: Austria becomes Austria-Hungary

Up to now, we’ve been looking at the longer-term trends and policy shifts among the European great powers. Now, we’ll take a look at the most multicultural and diverse polity of the early 20th century, the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary. Here is a map of Austria-Hungary at the start of the First World War:

A big central European empire: the second biggest empire in Europe at the time (after Russia). But that map manages to conceal nearly as much as it reveals. Here is a slightly more informative map, showing a similar map of ethnic and linguistic groups within the same geographical boundaries:

The ethnic groups of Austria-Hungary in 1910. Based on Distribution of Races in Austria-Hungary by William R. Shepherd, 1911. City names have been changed to those in use since 1945. (via Wikipedia)

This second map shows much more of the political reality of the empire — and these are merely the largest, most homogenous groupings — and why the Emperor was so sensitive to chauvinistic and nationalistic movements that appeared to threaten the stability of the realm. If anything, that map shows the southern regions of the empire — Croatia-Slavonia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina — to be more ethnically and linguistically compatible than almost any other region (which neatly illustrates some of the limitations of this form of analysis — layering on religious differences would make the map far more confusing, and yet in some ways more explanatory of what happened in 1914 … and, for that matter, from 1992 onwards).

Austria 1815-1866

For some reason, perhaps just common usage in history texts, I had the distinct notion that the Austrian Empire was a relatively continuous political and social structure from the Middle Ages onward. In reading a bit more on the nineteenth century, I find that the Austrian Empire was only “founded” in 1804 (according to Wikipedia, anyway). “Austria” as a concept certainly began far earlier than that! Austria was the general term for the personal holdings of the head of the Habsburgs. The title of Holy Roman Emperor had been synonymous with the Austrian head of state almost continuously since the fifteen century: that continuity was finally broken in 1806 when Emperor Francis II formally dissolved the Holy Roman Empire due to the terms of the Treaty of Pressburg, through which Napoleon stripped away many of the core holdings of the empire (including the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Kingdom of Württemberg) to create a new German proto-state called the Confederation of the Rhine.

The Confederation lasted until 1813, as Napoleon’s empire ebbed westward across the Rhine before the Prussian, Austrian, and Russian armies. After the Battle of Leipzig (also known as the Battle of Nations for the many different armies involved), several of the constituent parts of the Confederation defected to the allies. As part of the re-alignment of borders, treaties, and affiliations during the Congress of Vienna, both Prussia and Austria were added to the successor entity called the German Confederation, but Austria was the acknowledged leader of the organization.

The Rise of Prussia and the eclipse of Austria

The Kingdom of Prussia was the rising power within the German Confederation, and it was likely that at some point the Prussians would attempt to challenge Austria for the leadership of Germany. That situation arose (or, if you’re a fan of the “Bismarck had a master plan” theory, was engineered) over the dispute with Denmark over the duchies of Holstein and Schleswig.Denmark was not part of the confederation, but the two duchies were within it: the right of succession to the the two ducal titles were a point of conflict between the Kingdom of Denmark (whose monarch was also in his own person the duke of both Schleswig and Holstein) and the leading powers of the confederation, Austria and Prussia. When the King of Denmark died, by some legal views, the right of succession to each of the ducal seats was now open to dispute (because they were not formally part of Denmark, despite the King having held those titles personally).

In Denmark proper, the recently adopted constitution provided for a greater degree of democratic representation, but the political system in the two duchies was much more tailored to the interests and representation of the landowning classes (who were predominantly German-speaking) over the commoners (who were Danish-speakers). After the new Danish King signed legislation setting up a common parliament for Denmark and Schleswig, Prussia invaded as part of a confederate army, and the Danes wisely retreated north, abandoning the relatively indefensible southern portion of the debated duchies. In short, the campaign went poorly for the Danes, but quite well for the Prussians and (to a lesser degree) the Austrians. Under the terms of the resulting Treaty of Vienna, Denmark renounced all claims to the duchies of Schleswig, Holstein, and Lauenburg to the Austrians and Prussians.

Austria’s reward for the campaign was the duchy of Holstein, while Prussia got Schleswig and Lauenburg (in the form of King Wilhelm taking on the rulership of the latter duchy in his own person). The two great powers soon found themselves at odds over the administration of the duchies, and Austria appealed their side of the dispute to the Diet (parliament) of the Confederation. Prussia declared this to be a violation of the Gastein Convention, and launched an invasion of Holstein in co-operation with some of the other Confederation states.

This was the start of the Austro-Prussian War, also known as the Seven Weeks’ War. The start of the conflict triggered an existing treaty between Prussia and Italy, bringing the Italian forces in to menace Austria’s southwestern frontier (Italy was eager to take the Italian-speaking regions of the Austrian Empire into their kingdom. As the Wikipedia entry notes, the war was not unwelcome to the respective leaders of the warring powers: “In Prussia king William I was deadlocked with the liberal parliament in Berlin. In Italy, king Victor Emmanuel II, faced increasing demands for reform from the Left. In Austria, Emperor Franz Joseph saw the need to reduce growing ethnic strife, by uniting the several nationalities against a foreign enemy.”

In his essay “Bismarck and Europe” (collected in From Napoleon to the Second International), A.J.P. Taylor notes that the war took time and effort to bring to fruition, but not for reasons you might expect:

The war between Austria and Prussia had been on the horizon for sixteen years. Yet it had great difficulty in getting itself declared. Austria tried to provoke Bismarck by placing the question of the duchies before the Diet on 1 June. Bismarck retaliated by occupying Holstein. He hoped that the Austrian troops there would resist, but they got away before he could catch them. On 14 June the Austrian motion for federal mobilization against Prussia was carried in the Diet. Prussia declared the confederation at an end; and on 15 June invaded Saxony. On 21 June, when Prussian troops reached the Austrian frontier, the crown prince, who was in command, merely notified the nearest Austrian officer that “a state of war” existed. That was all. The Italians did a little better La Marmora sent a declaration of war to Albrecht, the Austrian commander-in-chief, before taking the offensive. Both Italy and Prussia were committed to programmes which could not be justified in international law, and were bound to appear as aggressors if they put their claims on paper. The would, in fact, have been hard put to it to start the war if Austria had not done the job for them.

Strategically, the Austro-Prussian war was the first European war to reflect some of the lessons of the recently concluded American Civil War: railway transportation of significant forces to the front, and the relative firepower differences between muzzle-loading weapons (Austria) and breech-loading rifles (Prussia). In the decisive Battle of Königgrätz (or Sadová), Prussian firepower and strategic movement were the key factors, allowing the numerically smaller force to triumph — Austrian casualties were more than three times greater than those of the Prussian army. This was the last major battle of the war, with an armistice followed by the Peace of Prague ending hostilities.

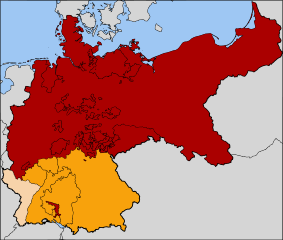

Initially, King Wilhelm had intended to utterly destroy Austrian power, possibly even to the extent of occupying significant portions of Austria, but Bismarck persuaded him that Prussia would be better served by offering a relatively lenient set of terms and working toward an alliance with the defeated Austrians than by the wholesale destruction of the balance of power. Austria lost the province of Venetia to Italy (although it was legally ceded to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Italy). The German Confederation was replaced by a new North German Confederation led by Prussia’s King Wilhelm I as president, and Austria’s minor German allies were faced with a reparations bill to be paid to Prussia for their choice of allies in the war. (Liechtenstein at this time was separated from Austria and declared itself permanently neutral … I’d always wondered when that micro-state had popped into existence.)

Initially, King Wilhelm had intended to utterly destroy Austrian power, possibly even to the extent of occupying significant portions of Austria, but Bismarck persuaded him that Prussia would be better served by offering a relatively lenient set of terms and working toward an alliance with the defeated Austrians than by the wholesale destruction of the balance of power. Austria lost the province of Venetia to Italy (although it was legally ceded to Napoleon III, who in turn ceded it to Italy). The German Confederation was replaced by a new North German Confederation led by Prussia’s King Wilhelm I as president, and Austria’s minor German allies were faced with a reparations bill to be paid to Prussia for their choice of allies in the war. (Liechtenstein at this time was separated from Austria and declared itself permanently neutral … I’d always wondered when that micro-state had popped into existence.)

Aftermath and constitutional change

After a humiliating defeat by Prussia, the Austrian Emperor was faced with the need to rally the empire, and the Hungarian nationalists took this opportunity to again demand special rights and privileges within the empire. Hungary had always been, legally speaking, a separate kingdom within the empire that just happened to share a monarch with the rest of the empire. In 1867, this situation was recognized in the Compromise of 1867, after which the Austrian Empire was replaced by the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

The necessity of satisfying Hungarian nationalist aspirations within the empire made Austria-Hungary appear as a political basket case to those more familiar with less ethnically, socially, and linguistically diverse polities than the Austrian Empire. From a more nationalistic viewpoint the political arrangements required to keep the empire together (mainly the issues in keeping Hungary happy) created a political system that appeared better suited to an asylum Christmas concert than a modern, functioning empire. In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark explains the post-1867 government structure briefly:

Shaken by military defeat, the neo-absolutist Austrian Empire metamorphosed into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Under the Compromise hammered out in 1867 power was shared out between the two dominant nationalities, the Germans in the west and the Hungarians in the east. What emerged was a unique polity, like an egg with two yolks, in which the Kingdom of Hungary and a territory centred on the Austrian lands and often called Cisleithania (meaning ‘the lands on this side of the River Leithe’) lived side by side within the translucent envelope of a Habsburg dual monarchy. Each of the two entities had its own parliament, but there was no common prime minister and no common cabinet. Only foreign affairs, defence and defence-related aspects of finance were handled by ‘joint ministers’ who were answerable directly to the Emperor. Matters of interest to the empire as a whole could not be discussed in common parliamentary session, because to do so would have implied that the Kingdom of Hungary was merely the subordinate part of some larger imperial entity. Instead, an exchange of views had to take place between the ‘delegations’, groups of thirty delegates from each parliament, who met alternately in Vienna and Budapest.

Along with the bifurcation between Cisleithania and Transleithania (Hungary), the two governments handled the demands of their respective majority and minority subjects quite differently: the Hungarian government actively suppressed minorities and attempted to impost Magyarization programs through the schools to stamp out as much as they could of other linguistic and ethnic communities. The Hungarian plurality (about 48 percent of the population) controlled 90 percent of the seats in parliament, and the franchise was limited to those with landholdings. The lot of minorities in Cisleithania was much easier, as the government eventually extended the franchise to almost all adult men by 1907, although this did not completely address the linguistic demands of various minority groups.

Hungary also actively prevented any kind of political move to create a Slavic entity within the empire (in effect, turning the Dual Monarchy into a Triple Monarchy), for fear that Hungarian power would be diluted and also for fear of encouraging demands among the other minority groups in the Hungarian kingdom.

Rumours of the death of Austria: mainly in hindsight, not prognostication

After World War One, many memoirs and histories made reference to the inevitability of Austrian decline. Most of these “memories” appear to have been constructed after the fact, rather than being accurate views of the reality before the war began. Christopher Clark notes:

Evalutating the condition and prospects of the Austro-Hungarian Empire on the eve of the First World War confronts us in an acute way with the problem of temporal perspective. The collapse of the empire amid war and defeat in 1918 impressed itself upon the retrospective view of the Habsburg lands, overshadowing the scene with auguries of imminent and ineluctable decline. The Czech national activist Edvard Beneš was a case in point. During the First World War, Beneš became the organizer of a secret Czech pro-independence movement; in 1918, he was one of the founding fathers of the new Czechoslovak nation-state. But in a study of the “Austrian Problem and the Czech Question” published in 1908, he had expressed confidence in the future of the Habsburg commonwealth. “People have spoken of the dissolution of Austria. I do not believe in it at all. The historic and economic ties which bind the Austrian nations to one another are too strong to let such a thing happen.”

Austria’s economy

Far from being an economic basket case, Austrian economic growth topped 4.8% per year before the start of WW1 (Christopher Clark):

The Habsburg lands passed during the last pre-war decade through a phase of strong economic growth with a corresponding rise in general prosperity — an important point of contrast with the contemporary Ottoman Empire, but also with another classic collapsing polity, the Soviet Union of the 1980s. Free markets and competition across the empire’s vast customs union stimulated technical progress and the introduction of new products. The sheer size and diversity of the double monarchy meant that new industrial plants benefited from sophisticated networks of cooperating industries underpinned by an effective transport infrastructure and a high-quality service and support sector. The salutary economic effects were particularly evident in the Kingdom of Hungary.

Part Six: The Anglo-German naval race

Even after the creation of the German Reich in 1871, Germany was not seen (by the British government) to be a major threat to British interests: Germany had no significant presence beyond Europe to worry the Colonial Office, and instead was seen as a potentially useful balancing factor in the European theatre. That all changed with the accession of Kaiser Wilhelm II as explained by Christopher Clark in The Sleepwalkers:

The 1890s were […] a period of deepening German isolation. A commitment from Britain remained elusive and the Franco-Russian Alliance seemed to narrow considerably the room for movement on the continent. Yet Germany’s statesmen were extraordinarily slow to see the scale of the problem, mainly because they believed that the continuing tension between the world empires was in itself a guarantee that these would never combine against Germany. Far from countering their isolation through a policy of rapprochement, German policy-makers raised the quest for self-reliance to the status of a guiding principle. The most consequential manifestation of this development was the decision to build a large navy.

In the mid-1890s, after a long period of stagnation and relative decline, naval construction and strategy came to occupy a central place in German security and foreign policy. Public opinion played a role here — in Germany, as in Britain, big ships were the fetish of the quality press and its educated middle-class readers. The immensely fashionable “navalism” of the American writer Alfred Thayer Mahan also played a part. Mahan foretold in The Influence of Sea Power upon History: 1660–1783 (1890) a struggle for global power that would be decided by vast fleets of heavy battleships and cruisers. Kaiser Wilhelm II, who supported the naval programme, was a keen nautical hobbyist and an avid reader of Mahan; in the sketchbooks of the young Wilhelm we find many battleships — lovingly pencilled floating fortresses bristling with enormous guns. But the international dimension was also crucial: it was above all the sequence of peripheral clashes with Britain that triggered the decision to acquire a more formidable naval weapon. After the Transvaal episode, the Kaiser became obsessed with the need for ships, to the point where he began to see virtually every international crisis as a lesson in the primacy of naval power.

The Royal Navy (RN) had been Britain’s most obvious sign of global dominance, and Britain’s fleets had gone through many technological changes over the century since Waterloo. What had been for centuries a slow, steady process of gradual improvement and incremental change suddenly became the white-hot centre of rapid, even revolutionary, change:

At the same time that you need to add armour to protect the ship, you also need to mount heavier, larger guns. Between placing your order with the shipyard for a new ship, the metallurgical wizards may have (and frequently did) come up with bigger, better guns that could defeat the armour on your not-yet-launched ship. Oh, and you now needed to revise the design of the ship to carry the newer, heavier guns, too.

The ship designers were in a race with the gun designers to see who could defeat the latest design by the other group. It’s no wonder that ships could become obsolete between ordering and coming into service: sometimes, they could become obsolete before launch.

The weapons themselves were undergoing change at a relatively unprecedented rate. As late as the mid-1870′s, a good case could be made for muzzle-loading cannon being mounted on warships: until the gas seal of the breech-loader could be made safe, muzzle-loaders had an advantage of not killing their own crews at distressingly high frequency. Once that technological handicap had been overcome, then the argument came down to the best way to mount the weapons: turrets or barbettes.

The RN’s international prestige invited envious imitators (like Wilhelm) and challengers (the United States Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy), but the RN was the supreme naval power against which all other nations measured themselves. In 1889, parliament passed the Naval Defence Act, which specified that the Royal Navy would be maintained at the “two-power standard”: that the RN’s fleet of capital ships would be at least equal to the number of battleships maintained by the next two largest navies (at that time, the French and Russian navies). The increased spending allowed ten battleships plus cruisers and torpedo boats to be added to the fleet … but the French and Russian navies added twelve battleships between them over the same period of time. “Another British expansion, known as the Spencer Programme, followed in 1894 aimed to match foreign naval growth at a cost of over £31 million. Instead of deterring the naval expansion of foreign powers, Britain’s Naval Defence Act contributed to a naval arms race. Other powers including Germany and the United States bolstered their navies in the following years as Britain continued to increase its own naval expenditures.”

In The War That Ended Peace, Margaret MacMillan describes the implicit power of the RN in peacetime:

In August 1902 another great naval review took place at Spithead in the sheltered waters between Britain’s great south coast port of Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight, this time to celebrate the coronation of Edward VII. Because he had suddenly come down with appendicitis earlier in the summer, the coronation itself and all festivities surrounding it had been postponed. As a result, most of the ships from foreign navies (except those of Britain’s new ally Japan) as well as those from the overseas squadrons of the British navy had been obliged to leave. The resulting smaller review was, nevertheless, The Times said proudly, a potent display of Britain’s naval might. The ships displayed at Spithead were all in active service and all from the fleets already in place to guard Britain’s home waters. “The display may be less magnificent than the wonderful manifestation of our sea-power witnessed in the same waters five years ago. But it will demonstrate no less plainly what that power is, to those who remember that we have a larger number of ships in commission on foreign stations now than we had then, and that we have not moved a single ship from Reserve.” “Some of our rivals,” The Times warned, “have worked with feverish activity in the interval, and they are steadily increasing their efforts. They should know that Britain remained vigilant and on guard, and prepared to spend whatever funds were necessary to maintain its sovereignty of the seas.”

Admiral Fisher’s new broom

In 1904, Admiral Sir John “Jackie” Fisher was appointed as First Sea Lord (the professional head of the RN, reporting to the First Lord of the Admiralty, a cabinet minister). Fisher was a full-steam-ahead reformer, with vast notions of modernizing and reforming the navy. He was brilliant, argumentative, abrasive, tactless, and aggressive but could also be charming and persuasive. “When addressing someone he could become carried away with the point he was seeking to make, and on one occasion, the king asked him to stop shaking his fist in his face.” (Fortunately for Fisher, the king was a personal friend, so this did not hinder his career.)Margaret MacMillan describes him in The War That Ended Peace:

Jacky Fisher, as he was always known, shoots through the history of the British navy and of the prewar years like a runaway Catharine wheel, showering sparks in all directions and making some onlookers scatter in alarm and others gasp with admiration. He shook the British navy from top to bottom in the years before the Great War, bombarding his civilian superiors with demands until they usually gave way and steamrollering over his opponents in the navy. He spoke his mind freely in his own inimitable language. His enemies were “skunks”, “pimps”, “fossils”, or “frightened rabbits”. Fisher was tough, dogged and largely immune to criticism, not surprising perhaps in someone from a relatively modest background who had made his own way in the navy since he was a boy. He was also supremely self-confident. Edward VII once complained that Fisher did not look at different aspects of an issue. “Why should I waste my time,” the admiral replied, “looking at all sides when I know my side is the right side?”

Fisher had been a maverick throughout his career (which makes it even more amazing that he eventually did rise to become First Sea Lord), as his actions when he took command of the Mediterranean Fleet clearly illustrate:

A programme of realistic exercises was adopted including simulated French raids, defensive manoeuvres, night attacks and blockades, all carried out at maximum speed. He introduced a gold cup for the ship which performed best at gunnery, and insisted upon shooting at greater range and from battle formations. He found that he too was learning some of the complications and difficulties of controlling a large fleet in complex situations, and immensely enjoyed it.

Notes from his lectures indicate that, at the start of his time in the Mediterranean, useful working ranges for heavy guns without telescopic sights were considered to be only 2000 yards, or 3000-4000 yards with such sights, whereas by the end of his time discussion centred on how to shoot effectively at 5000 yards. This was driven by the increasing range of the torpedo, which had now risen to 3000-4000 yards, necessitating ships fighting effectively at greater ranges. At this time he advocated relatively small main armaments on capital ships (some had 15 inch or greater), because the improved technical design of the relatively small (10 inch) modern guns allowed a much greater firing rate and greater overall weight of broadside. The potentially much greater ranges of large guns was not an issue, because no one knew how to aim them effectively at such ranges. He argued that “the design of fighting ships must follow the mode of fighting instead of fighting being subsidiary to and dependent on the design of ships.” As regards how officers needed to behave, he commented, “‘Think and act for yourself’ is the motto for the future, not ‘Let us wait for orders’.”

Lord Hankey, then a marine serving under Fisher, later commented, “It is difficult for anyone who had not lived under the previous regime to realize what a change Fisher brought about in the Mediterranean fleet. … Before his arrival, the topics and arguments of the officers messes … were mainly confined to such matters as the cleaning of paint and brasswork. … These were forgotten and replaced by incessant controversies on tactics, strategy, gunnery, torpedo warfare, blockade, etc. It was a veritable renaissance and affected every officer in the navy.” Charles Beresford, later to become a severe critic of Fisher, gave up a plan to return to Britain and enter parliament, because he had “learnt more in the last week than in the last forty years”.

One of his first changes was to sell nearly one hundred elderly ships and move dozens of less capable vessels from the active list to the reserve fleet, to free up the crews (and the maintenance budget) for more modern vessels, describing the ships as “too weak to fight and too slow to run away”, and “a miser’s hoard of useless junk”. Between his reforms as Third Sea Lord (where he had championed the development of the modern destroyer and vastly increased the efficiency and productivity of the shipyards) and his new role as First Sea Lord, Fisher was able to get more done even on a budget that dropped nearly 10% in the year of his appointment than his predecessor had managed.

HMS Dreadnought and the naval revolution

Fisher was not a naval designer, but he knew how to push new ideas to the front and get them adopted. The one thing that most people remember him for is the revolutionary battleship HMS Dreadnought, the first all big gun, fast steam turbine powered battleship, and when she went into commission, she signified the obsolescence of every other capital ship in every navy from that moment onwards.

Dreadnought was the platonic ideal of a battleship: she was faster than any other capital ship in any other navy, her guns were at least the equivalent in range, rate of fire, and throw of shot, and her armour was sufficient to allow her to take punishment from opposing ships and still deal out damage herself. She was the first British ship to be equipped with electrical controls allowing the entire main armament to be fired from a central location. Thanks to Fisher’s earlier efforts with the shipyards, Dreadnought took just a year to build — far faster than any other battleship had been built.

The “entirely crazy Dreadnought policy of Sir J. Fisher and His Majesty”

The Kaiser was not happy with the new British battleship, as it had been German policy since his accession to build up the German navy to at least provide a tool for pressuring Britain (if not for actually confronting the Royal Navy in battle). Now his entire naval plan had been upset by the Dreadnought revolution. Margaret MacMillan:

As far as the Kaiser and [Admiral] Tirpitz were concerned the responsibility for taking the naval race to a new level rested with what Wilhelm called the “entirely crazy Dreadnought policy of Sir J. Fisher and His Majesty”. The Germans were prone to see Edward VII as bent on a policy of encircling Germany. The British had made a mistake in building dreadnoughts and heavy cruisers, in Tirpitz’s view, and they were angry about it: “This annoyance will increase as they see that we follow them immediately.” […] Who could tell what the British might do? Did their history not show them to by hypocritical, devious and ruthless? Fears of a “Kopenhagen”, a sudden British attack just like the one in 1807 when the British navy had bombarded Copenhagen and seized the Danish fleet, were never far from the thoughts of the German leadership once the naval race had started.

German fears of British attack increased almost in lockstep with British fears of German attack (William Le Queux had his equivalents among the German press and popular novelists). The thought had actually occurred to Fisher himself, who outlined a possible coup de main against the German fleet. The king responded “My God, Fisher, you must be mad!” and the suggestion was ignored, thankfully.

The popular worries about an attack from Britain fed the support for the German Navy laws, which funded dreadnought and battlecruiser building programs. In direct proportion, the increased German support for their naval expansion worked to the advantage of British politicians who wanted to build more dreadnoughts of their own. And, in fairness, Britain risked far more by allowing an enlarged German navy than Germany risked by stopping their building program … but in either case, the fear of popular unrest kept the shipyards humming anyway. As Churchill later wrote, “The Admiralty had demanded six ships; the economists offered four; and we finally compromised on eight.”

Part Seven: Russia’s Oriental catastrophe

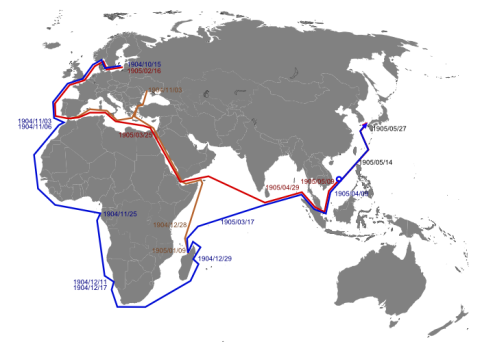

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 was a huge upset, as all the great powers expected Russia to crush the upstart Japanese and put them back “in their place”. Japan’s stunning naval and military successes at the Battle of the Yellow Sea, Tsushima and Port Arthur left Russia in a potentially disastrous situation, with utter undeniable defeat in the East and revolution brewing at home.

The war came about due to irreconcilable differences in the expansionary plans of the two empires: Russia wanted control of Manchuria and Japan wanted control of Korea, but neither side trusted the other enough to make negotiations work. Japan decided to initiate the conflict with a surprise attack on the Russian naval forces in Port Arthur (now known as the Lüshunkou District of Dalian in China’s Liaoning province). From that point onwards, Japan maintained the initiative, forcing Russia to react and interrupting Russian moves on land and at sea.

After the defeat of the original Russian fleet in the Pacific, the Baltic Fleet was re-tasked and set out to avenge the loss. The fleet’s luck was terrible to begin with, as shortly after passing between Sweden and Denmark and sailing out into the North Sea, lookouts on the Russian battleships spotted Japanese forces and the fleet opened fire. Twenty minutes, later the enemy was in tatters … unfortunately, the “enemy” were British fishing trawlers. Given the massive firepower of even pre-dreadnought ships, the casualties were surprisingly light: one trawler sunk, two dead, and many wounded. Not long afterward, a Russian ship in the fleet was mis-identified as a Japanese ship and nearly sunk by friendly fire. The nearest Japanese ship was still thousands of miles to the East.Despite nearly starting a war with the Royal Navy over the Dogger Bank incident (Britain and Japan had signed an alliance in 1902), Admiral Rozhdestvensky was unapologetic and insisted it was the trawlers’ fault and his ships were perfectly entitled to defend themselves from Japanese attackers. As a result of the Russian mistake, Britain refused to allow the fleet passage through the Suez Canal, forcing them to take the far longer trip around Africa instead. If ever a military expedition has had bad omens, the sortie of the Baltic Fleet — now renamed the Second Pacific Squadron for this mission — must be one of the best examples.

When the Russian and Japanese fleets met in the Tsushima Straits, Admiral Tōgō managed to “cross the T” of the Russians, allowing his ships to use their full broadside armament against only the forward-facing guns of the Russian ships. In the end, the Second Pacific Squadron lost all eleven battleships and over 4,000 men killed, another 5,900 captured, and 1,800 interned. Japanese losses were trivial in comparison: three torpedo boats sunk, 117 men killed and about 500 wounded.

There were no major subsequent battles, and Russia was forced to sign the Treaty of Portsmouth to end the war in September 1905. Despite the Tsar’s initial instructions to the Russian delegation, the Russians agreed to recognize Japan’s sphere of influence in Korea, withdraw their troops from Manchuria, and to give up their lease on Port Arthur and Talien. The reaction in both countries was similar: political unrest. Japanese public opinion was that they had been cheated of their full reward from the war, and the government fell in the aftermath. Russians were even more angry and the result was revolution.

The (first) Russian revolution

While the result of the Russo-Japanese war was the trigger for the 1905 Revolution, it was far from being the only grievance. Margaret MacMillan wrote in The War That Ended Peace:

In 1904 the Minister of the Interior, Vyacheslav Plehve, is reported to have said that Russia needed “a small victorious war” which would take the minds of the Russian masses off “political questions”.

The Russo-Japanese War showed the folly of that idea. In its early months Plehve himself was blown apart by a bomb; towards its end the newly formed Bolsheviks tried to seize Moscow. The war served to deepen and bring into sharp focus the existing unhappiness of many Russians with their own society and its rulers. As the many deficiencies, from command to supplies, of the Russian war effort became apparent, criticism grew, both of the government and, since the regime was a highly personalized one, of the Tsar himself. In St. Petersburg a cartoon showed the Tsar with his breeches down being beaten while he says, “Leave me alone. I am the autocrat!” Like the French Revolution, with which it had many similarities, the Russian Revolution of 1905 broke old taboos, including the reverence surrounding the country’s ruler. It seemed to officials in St. Petersburg a bad omen that the Empress had hung a portrait of Marie Antoinette, a gift from the French government, in her rooms.

In December 1904, a strike in St. Petersburg triggered sympathy strikes in other industries, leading to 80,000 workers and supporters protesting in the city. In January 1905, a mass march by the strikers to the Winter Palace was met with rifle fire from the defending troops. Casualty estimates range from 200 to over 1,000 on Bloody Sunday. The strikes and protests spread beyond St. Petersburg, to the point that the government was threatened. Eventually the Tsar was persuaded to offer concessions :

Under huge pressure from his own supporters, the Tsar reluctantly issued a manifesto in October promising a responsible legislature, the Duma, as well as civil rights.

As so often happens in revolutionary moments, the concessions only encouraged the opponents of the regime. It appeared to be close to collapsing with its officials confused and ineffective in the face of such widespread disorder. That winter a battalion from Nichlas’s own regiment, the Preobrazhensky Guards, which had been founded by Peter the Great, mutinied. A member of the Tsar’s court wrote in his diary: “This is it.” Fortunately for the regime, its most determined enemies were disunited and not yet ready to take power while moderate reformers were prepared to support it in the light of the Tsar’s promises. Using the army and police freely, the government managed to restore order. By the summer of 1906 the worst was over — for the time being. The regime still faced the dilemma, though, of how far it could let reforms go without fatally undermining its authority. It was a dilemma faced by the French government in 1789 or the Shah’s government in Iran in 1979. Refusing demands for reform and relying on repression creates enemies; giving way encourages them and brings more demands.

Russia’s economy did recover eventually, but the political solution was not strong enough to stand the strains of another war any time soon. In some ways, it’s hard to imagine what the Russian leaders who advised the Tsar were thinking as the Russians continued to stir the pot in the Balkans…

Part Eight: Italy tips the first domino … in Africa

In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark talks about a war I don’t think I’d ever heard of … an Italian campaign against the Ottoman Empire:

At the end of September 1911, only six months after the foundation of Ujedinjenje ili smrt! [“Union or death!” aka The Black Hand], Italy launched an invasion of Libya. This unprovoked attack one one of the integral provinces of the Ottoman Empire triggered a cascade of opportunistic attacks on Ottoman-controlled territory in the Balkans.

Italy’s attack on the Ottoman Empire was literally planned to steal what is now Libya and incorporate it into a new Italian Empire. Although the formal war was over in thirteen months, indigenous Arabs were still fighting back twenty years later. This attack broke the public-but-informal international understandings about leaving the remaining parts of the Ottoman Empire alone to prevent the risk of great power struggles breaking out. Britain and France had gone to war in 1854 to ensure that Russia did not gain access to the straits and thus a warm-water route to the Mediterranean and the coastlines of southern Europe, but the outcome of both the 1870-71 Franco-Prussian War and the 1877-78 Russo-Turkish War (and the secret Reinsurance Treaty with Germany) meant that Russia’s hands were largely free as long as Constantinople and the straits were not directly attacked. Italy’s attack broke with that understanding, and could be said to have started the most recent (and also most fatal) scramble for territory in the Balkans.

However, Italy did not act completely outside the norm for a would-be great power: they had an understanding with the French government that was formalized in a secret treaty in 1902 — Italy would not oppose French designs on Tunisia in exchange for French acceptance of Italy’s similar hopes for Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (modern day Libya). Italy’s attack was only possible because of the anomaly of the British position in Egypt: although still formally part of the Ottoman Empire, day-to-day Egyptian affairs were run by or overseen by British officials. Egypt was militarily occupied, but not a colony of the British Empire, and the country was — in theory — still run by the government of the Khedive. The Ottomans could not move formed bodies of troops through Egypt, and the Ottoman navy did not have the ships to transport them from Anatolia directly to Libya. This gave Italy the opportunity to concentrate against the weaker Ottoman forces.

The otherwise obscure Italo-Turkish War was interesting for several reasons, as the Wikipedia article notes:

Although minor, the war was a significant precursor of the First World War as it sparked nationalism in the Balkan states. Seeing how easily the Italians had defeated the weakened Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League attacked the Ottoman Empire before the war with Italy had ended.The Italo-Turkish War saw numerous technological changes, notably the airplane. On October 23, 1911, an Italian pilot, Captain Carlo Piazza, flew over Turkish lines on the world’s first aerial reconnaissance mission, and on November 1, the first ever aerial bomb was dropped by Sottotenente Giulio Gavotti, on Turkish troops in Libya, from an early model of Etrich Taube aircraft. The Turks, lacking anti-aircraft weapons, were the first to shoot down an aeroplane by rifle fire.

It was also in this conflict that the future first president of Turkey and leader of the Turkish War of Independence, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, distinguished himself militarily as a young officer during the Battle of Tobruk.

Although Italy ended up with possession of the disputed land, it did not come easily or cheaply:

The invasion of Libya was a costly enterprise for Italy. Instead of the 30 million lire a month judged sufficient at its beginning, it reached a cost of 80 million a month for a much longer period than was originally estimated. The war cost Italy 1.3 billion lire, nearly a billion more than Giovanni Giolitti estimated before the war. This ruined ten years of fiscal prudence.

After the withdrawal of the Ottoman army the Italians could easily extend their occupation of the country, seizing East Tripolitania, Ghadames, the Djebel and Fezzan with Murzuk during 1913. The outbreak of the First World War with the necessity to bring back the troops to Italy, the proclamation of the Jihad by the Ottomans and the uprising of the Libyans in Tripolitania forced the Italians to abandon all occupied territory and to entrench themselves in Tripoli, Derna, and on the coast of Cyrenaica. The Italian control over much of the interior of Libya remained ineffective until the late 1920s, when forces under the Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani waged bloody pacification campaigns. Resistance petered out only after the execution of the rebel leader Omar Mukhtar on September 15, 1931. The result of the Italian colonisation for the Libyan population was that by the mid-1930s it had been cut in half due to emigration, famine, and war casualties. The Libyan population in 1950 was at the same level as in 1911, approximately 1.5 million in 1911.

The war ended well — at least geographically speaking — for Italy, having gained title not only to Libya but also to the Dodecanese: a group of twelve large and about 150 small islands in the Aegean Sea. The largest and most economically valuable island was Rhodes, which became a useful base for Italian forces for more than 40 years. The treaty ending the Italo-Turkish War required Italy to vacate the islands, but due to both fuzzy wording and the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, Italy managed to retain possession.

The Ottoman tide ebbs

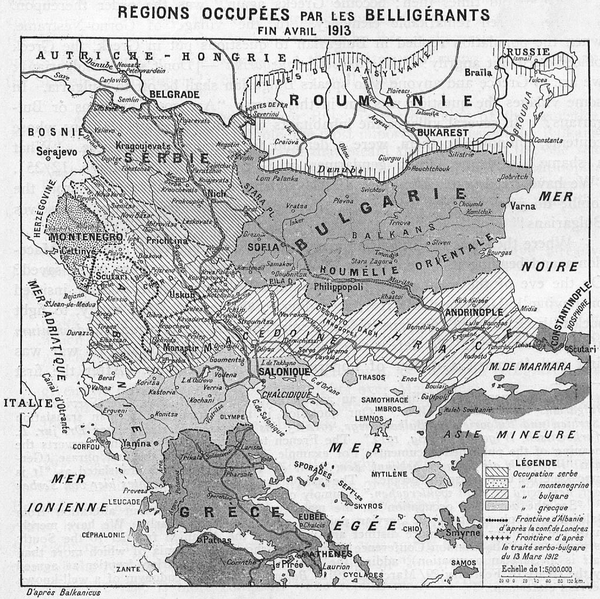

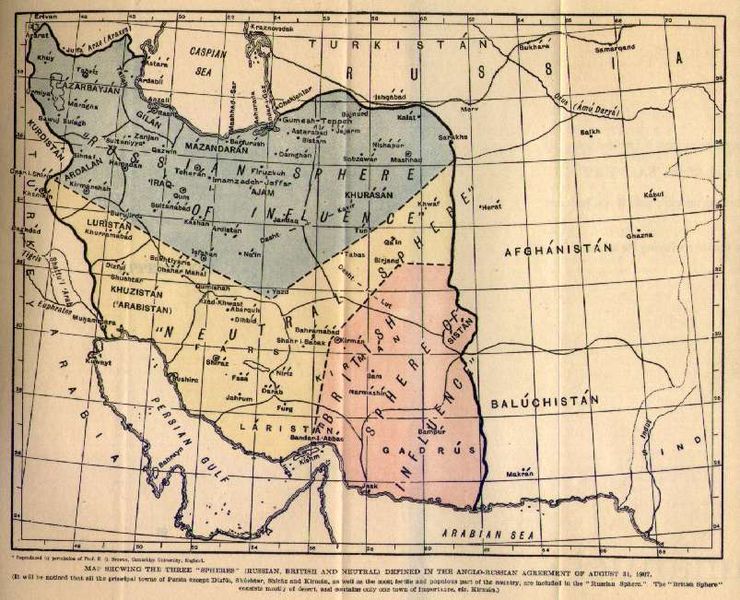

The remaining Ottoman territories in Europe were under constant pressure both from external forces (Austria and Russia) and internal linguistic, religious, and cultural separatist movements. Austria preferred to view the separatists as potential new provinces for the Dual Monarchy, while Russia saw the possibility of new independent Russophile political groupings that might allow indirect Russian access to the Mediterranean, bypassing Constantinople (or, perhaps more realistically, additional bases from which to launch an attack against the straits).Italy’s attack was the first domino falling. Christopher Clark writes:

The First World War was the Third Balkan War before it became the First World War. How as this possible? Conflicts and crises on the south-eastern periphery, where the Ottoman Empire abutted Christian Europe, were nothing new. The European system had always accommodated them without endangering the peace of the continent as a whole. But the last years before 1914 saw fundamental change. In the autumn of 1911, Italy launched a war of conquest on an African province of the Ottoman Empire, triggering a chain of opportunistic assaults on Ottoman territories across the Balkans. The system of geopolitical balances that had enabled local conflicts to be contained was swept away. In the aftermath of the two Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, Austria-Hungary faced a new and threatening situation on its south-eastern periphery, while the retreat of Ottoman power raised strategic questions that Russian diplomats and policy-makers found it impossible to ignore.

Margaret MacMillan, in The War That Ended Peace:

It was in the Balkans […] that the greatest dangers were to arise: two wars among its nations, one in 1912 and a second in 1913, nearly pulled the great powers in. Diplomacy, bluff and brinksmanship in the end saved the peace but although Europeans could not know it, they had had a dress rehearsal for the summer of 1914. As they say in the theatre, if that last run-through goes well, the opening night will be a disaster.

The First Balkan War of 1912 — A Pan-Slavic triumph

To some, the Balkans were a comic opera assemblage of exotic uniforms, passionate actors, indecipherable languages, a bit of bloodshed, but no real source of international danger or worry. Margaret MacMillan explains that much happened beneath the surface of the above-ground culture: much that portended danger to the entire region and beyond.

To the rest of Europe the Balkan states were something of a joke, the setting for tales of romance such as the Prisoner of Zenda or operettas (Montenegro was the inspiration for the The Merry Widow), but their politics were deadly serious — and frequently deadly with terrorist plots, violence and assassinations. In 1903 King Peter’s unpopular predecessor as King of Serbia and his equally unpopular wife had been thrown from the windows of the palace and their corpses hacked to pieces. […] The growth of national movements had welded peoples together but it had also divided Orthodox from Catholic or Muslim, Albanians from Slaves, and Croats, Serbs, Slovenes, Bulgarians or Macedonians from each other. While the peoples of the Balkans had coexisted and intermingled, often for long periods of peace through the centuries, the establishment of national states in the nineteenth century had too often been accompanied by burning of villages, massacres, expulsions of minorities and lasting vendettas.

Politicians who had ridden to power by playing on nationalism and with promises of national glory found they were in the grip of forces they could not always control. Secret societies, modelling themselves on an eclectic mix which included Freemasonry, the underground Carbonari, who had worked for Italian unity, the terrorists who more recently had frightened much of Europe, and old-style banditry, proliferated throughout the Balkans, weaving their way into civilian and military institutions of the states.

In addition to the ethnic, proto-national, cultural, and religious aspects of Balkan conflict, it was also an inter-generational conflict: