To the very young, to schoolteachers, as also to those who compile textbooks about constitutional history, politics, and current affairs, the world is a more or less rational place. They visualize the election of representatives, freely chosen from among those the people trust. They picture the process by which the wisest and best of these become ministers of state. They imagine how captains of industry, freely elected by shareholders, choose for managerial responsibility those who have proved their ability in a humbler role. Books exist in which assumptions such as these are boldly stated or tacitly implied. To those, on the other hand, with any experience of affairs, these assumptions are merely ludicrous. Solemn conclaves of the wise and good are mere figments of the teacher’s mind. It is salutary, therefore, if an occasional warning is uttered on this subject. Heaven forbid that students should cease to read books on the science of public or business administration — provided only that these works are classified as fiction. Placed between the novels of Rider Haggard and H.G. Wells, intermingled with volumes about ape men and space ships, these textbooks could harm no one. Placed elsewhere, among works of reference, they can do more damage than might at first sight seem possible.

C. Northcote Parkinson, “Preface”, Parkinson’s Law (and other studies in administration), 1957.

January 6, 2014

QotD: The illusion of a rational world

January 5, 2014

QotD: The Law of the Custom-Built Headquarters Building

Publishers have a strong tendency, as we know, to live in a state of chaotic squalor. The visitor who applies at the obvious entrance is led outside and around the block, down an alley and up three flights of stairs. A research establishment is similarly housed, as a rule, on the ground floor of what was once a private house, a crazy wooden corridor leading thence to a corrugated iron hut in what was once the garden. Are we not all familiar, moreover, with the layout of an international airport? As we emerge from the aircraft, we see (over to our right or left) a lofty structure wrapped in scaffolding. Then the air hostess leads us into a hut with an asbestos roof. Nor do we suppose for a moment that it will ever be otherwise. By the time the permanent building is complete the airfield will have been moved to another site.

The institutions already mentioned — lively and productive as they may be — flourish in such shabby and makeshift surroundings that we might turn with relief to an institution clothed from the outset with convenience and dignity. The outer door, in bronze and glass, is placed centrally in a symmetrical facade. Polished shoes glide quietly over shining rubber to the glittering and silent elevator. The overpoweringly cultured receptionist will murmur with carmine lips into an ice-blue receiver. She will wave you into a chromium armchair, consoling you with a dazzling smile for any slight but inevitable delay. Looking up from a glossy magazine, you will observe how the wide corridors radiate toward departments A, B, and C. From behind closed doors will come the subdued noise of an ordered activity. A minute later and you are ankle deep in the director’s carpet, plodding sturdily toward his distant, tidy desk. Hypnotized by the chief’s unwavering stare, cowed by the Matisse hung upon his wall, you will feel that you have found real efficiency at last.

In point of fact you will have discovered nothing of the kind. It is now known that a perfection of planned layout is achieved only by institutions on the point of collapse. This apparently paradoxical conclusion is based upon a wealth of archaeological and historical research, with the more esoteric details of which we need not concern ourselves. In general principle, however, the method pursued has been to select and date the buildings which appear to have been perfectly designed for their purpose. A study and comparison of these has tended to prove that perfection of planning is a symptom of decay. During a period of exciting discovery or progress there is no time to plan the perfect headquarters. The time for that comes later, when all the important work has been done. Perfection, we know, is finality; and finality is death.

C. Northcote Parkinson, “Plans And Plants, or the Administration Block”, Parkinson’s Law (and other studies in administration), 1957.

January 3, 2013

Comitology and the EU

Alexandra Swann notes that the great C. Northcote Parkinson predicted the EU’s decision-making mechanics with great accuracy:

If we listen to Daniel Guéguen, Professor of European Political and Administrative studies at the College of Europe, the Europhile madrassa, the equation spells the downfall of the European Union.

Guéguen has worked as a Brussels lobbyist for 35 years; he is a full time federast and one of the remaining true believers in the EU. Given his commitment to the EU project, when he deems its system of governance, comitology, “an infernal system” perhaps it’s time to listen.

The concept of Comitology was invented by the incomparable Professor C Northcote-Parkinson in his seminal work Parkinson’s law of 1958. It was meant as a satire but, like many of the best jokes, they either get elected or, in this case, embedded in the bureaucracy. Here is the Professor explaining the comitology and his equation:

x=(mo(a-d))/(y+p b1/2)

Where m = the average number of members actually present; o = the number of members influenced by outside pressure groups; a = the average age of the members; d = the distance in centimetres between the two members who are seated farthest from each other; y = the number of years since the cabinet or committee was first formed; p = the patience of the chairman, as measured on the Peabody scale; b = the average blood pressure of the three oldest members, taken shortly before the time of meeting. Then x = the number of members effectively present at the moment when the efficient working of the cabinet or other committee has become manifestly impossible. This is the coefficient of inefficiency and it is found to lie between 19.9 and 22.4. (The decimals represent partial attendance; those absent for a part of the meeting.)

This beautifully encapsulates the terrifying silliness of what is going on in the tubular steel and stripped Swedish pine chairs of Brussels, and for anyone with an interest in transparency or good governance, it is a serious concern. After all, under various estimates upwards of 75 per cent of our laws, the laws that govern the minutiae of our lives are made in the sterile Committee rooms of the Breydel, Berlyamont, Justis Lupsius and other buildings in the EU quarter of Brussels. That this cosmic joke now governs our lives is just a factor of the brobdingnagian reality of our membership of the EU.

August 13, 2010

UK to reduce number of senior officers in armed forces

In a desperate search for economies in the army, Royal Navy, and Royal Air Force, Liam Fox announced a good first step:

The number of senior military officers could be cut in an attempt to curb spending in the Ministry of Defence, the defence secretary, Liam Fox, said today.

In a speech setting out his vision for the future of the MoD, Fox said the reforms were intended to make the department leaner, less centralised and more effective.

He said military chiefs would be given greater control over the armed services as he attempted to sweeten what he described as “difficult and painful” cuts he blamed on the “dangerous deficit” left by the Labour government.

Fox said it was a “ghastly truth” that Labour had left the department with a £37bn “unfunded liability” over the next 10 years. However, he made no specific commitments on cuts, which are not expected to be announced until October.

It’s probably a safe bet that you could reduce the number of generals and admirals by half without in any measurable way decreasing the effectiveness of the armed forces — this is true in almost any nation’s armed forces, not just in Britain. Above the rank of Brigadier/Commodore, there are very few combat posts to be filled, but lots of administrative ones. When a senior officer transitions to being an administrator, their focus shifts from supporting the combat mission of the service to building their bureaucratic empire. It’s startling to see that an army of 100,000 troops “needs” 85,000 civil service workers to support it. (I’ve touched on this before.)

Each of the services has been starved of capital improvements so that any reduction in funding at this point will be very detrimental to long-term defence capabilities. The Royal Navy is starting to look more and more like a coastal defence force than a blue water navy . . . and getting rid of one or both of the new aircraft carriers would end Britain’s pretensions to be able to do any force projection at all (but Argentina would be happy to see it). The RAF had hoped to be next in line for shiny new aircraft to replace their current lot. The army has been wearing down their armoured vehicles at a steady pace and were also hoping for new, improved models in the immediate future.

In spite of the statements of the new coalition government, I don’t see why they’re bothering to replace Trident: you’ve already admitted that you can’t support the current force levels — which are clearly inadequate to meet the challenges of today, never mind those of tomorrow. Forcing the Trident replacement into the military budget could almost literally mean scrapping the rest of the RN just to retain those few nuclear submarines and their support structures.

October 8, 2009

British military establishment facing cuts under next government?

It would be too glib of me to suggest that the Ministry’s preferred way to respond to the Conservative opposition’s call “to cut MoD costs by 25%” would be to abandon the Royal Navy (or ground the Royal Air Force), but it’s hard to imagine them voluntarily cutting their own numbers:

Shadow defence secretary Liam Fox is expected to tell the party’s conference: “Some things will have to change and believe me, they will.”

The BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg said Mr Fox had asked for savings in bureaucracy – the MoD has 85,000 civil servants.

The Tories have pledged to cut overall Whitehall budgets by a third.

In his speech to party members in Manchester, Dr Fox will accuse Labour of having creating “a black hole” in defence budgets, which are affecting the war in Afghanistan and threatening to create an “on-going defence crisis for years to come”.

Of course, there’s nothing new about the administrative “tail” of the armed forces growing . . . C. Northcote Parkinson documented the phenomenon (PDF) back in 1955:

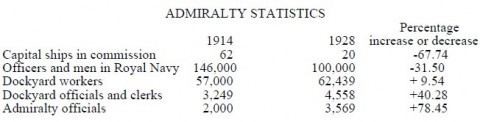

The accompanying table is derived from Admiralty statistics for 1914 and 1928. The criticism voiced at the time centered on the comparison between the sharp fall in numbers of those available for fighting and the sharp rise in those available only for administration, the creation, it was said, of “a magnificent Navy on land.” But that

comparison is not to the present purpose. What we have to note is that the 2,000 Admiralty officials of 1914 had become the 3,569 of 1928; and that this growth was unrelated to any possible increase in their work. The Navy during that period had diminished, in point of fact, by a third in men and two-thirds in ships. Nor, from 1922 onwards, was its strength even expected to increase, for its total of ships (unlike its total of officials) was limited by the Washington Naval Agreement of that year. Yet in these circumstances we had a 78.45 percent increase in Admiralty officials over a period of fourteen years; an average increase of 5.6 percent a year on the earlier total. In fact, as we shall see, the rate of increase was not as regular as that. All we have to consider, at this stage, is the percentage rise over a given period.

July 11, 2009

Parkinson: the man behind “the Law”

He may be less familiar now, but most of us have heard of his most popular work: Parkinson’s Law:

The book expanded on an article of his first published in The Economist in November 1955. Illustrated by Britain’s then leading cartoonist, Osbert Lancaster, the book was an instant hit. It was wrapped around the author’s “law” that “work expands to fill the time available for its completion”. Thus, Parkinson wrote, “an elderly lady of leisure can spend the entire day in writing and dispatching a postcard to her niece at Bognor Regis . . . the total effort that would occupy a busy man for three minutes all told may in this fashion leave another person prostrate after a day of doubt, anxiety and toil.”

Parkinson’s barbs were directed first and foremost at government institutions — he cited the example of the British navy where the number of admiralty officials increased by 78% between 1914 and 1928, a time when the number of ships fell by 67% and the number of officers and men by 31%. But they applied almost equally well to private industry, which was at the time bloated after decades spent adding layers and layers of managerial bureaucracy.

(Crossposted to the old blog, http://bolditalic.com/quotulatiousness_archive/005572.html.