In economics, Gresham’s Law states that “bad money drives out good”, that may need to be reformulated as it applies to modern standards of photography in a formulation something like: “bad photos drive out good photos“:

“Art is like a joke, either you get it or you don’t.” So it was explained to me in the late 1970s by photographer Randy Eriksen, whose cheeky observation about the importance of context to one’s appreciation of either comedy or art could have been a parenthetical second subtitle for author and educator Kim Beil’s Good Pictures: A History of Popular Photography (Stanford University Press, 2020).

Beil’s episodic and highly readable book identifies 50 photographic trends — illustrated by hundreds of vintage and contemporary photographs — that have guided the aesthetics of photography since 1851, when a group of American daguerreotypes made a splash at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London. Back in 1851, context mostly equaled 1851, as the latest photo technology of the day played a major role in how Victorians decided that one picture was good and another was not.

[…]

Beil’s own context began in Albany, New York, where she grew up. “My mom was into photography,” Beil tells me over the phone. “She was the one who took the pictures in my family. When my parents got me my first camera, a Nikon FE, they made me attend a class offered by the camera store. I remember it was held in this dark ballroom at an Albany hotel. It was me and a bunch of middle-aged men. That’s where I learned about 35mm cameras, f-stops, and shutter speeds.”

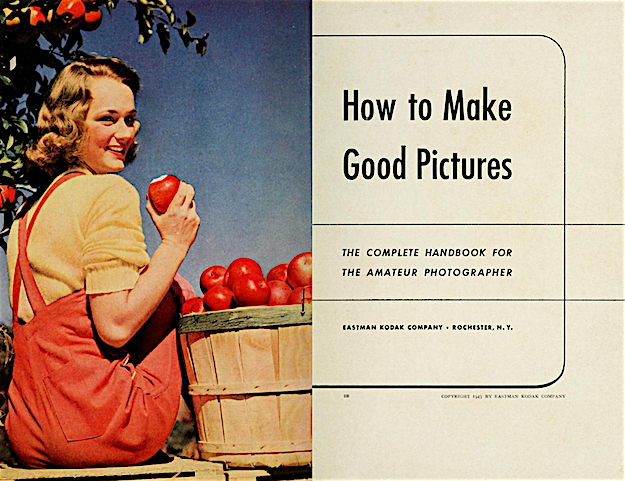

“How To Make Good Pictures” (Rochester, NY: Eastman Kodak Co., 1943).

Source: Collection of the Prelinger Library, via Collectors Weekly.Beil also learned from various “How to Make Good Pictures” manuals published by Kodak, which also hailed from upstate New York. “I’m pretty sure I internalized the advice I read in ‘How to Make Good Pictures’,” Beil says of her early aesthetic indoctrination, “things like avoiding centering your subject in the frame, the rule of thirds, shooting during ‘golden hour’, all that conventional wisdom.”

[…]

“Intention is central to the way I think about art, and maybe even how we define it,” Beil agrees. “Take lens flare: I think the power of lens flare comes from its initial unintentional use by people who were just taking casual pictures without any premeditation, without much intention.” In these sorts of photographs, Beil says, lens flare was an amateur mistake that conferred “a kind of authenticity to an image.” That’s why advertisers find lens flare so appealing. “Because we still associate it with authenticity,” Beil says, “it makes an advertising photo seem more real, maybe even spontaneous.”

Today, lens flare is so widely used, so intentional, that billions of smartphone cameras offer multiple variations of this former failing in the form of filters, which can be activated with a click or a swipe. “Everything can be achieved and there are no more accidents,” Beil says of photography in the 2020s, “so photographers look to things that happened before to reinsert some kind of authenticity into their pictures.” Thanks to technology, photographers can now pretend to take pictures as if they lacked the tools to make their pictures, well, good.

The problem, of course, is that technology is intrusive, inserting itself into aesthetics and even cultural paradigms without being invited to do so. “We have a situation today,” Beil says, “in which our smartphone cameras are producing pictures according to the criteria of software designers, who have made a lot of egregious assumptions about the tonality of skin color.” According the Beil, because the sample sets used by software designers have historically included more pictures of light skin tones than dark skin tones, the colors captured by our smartphone cameras do a better job of reproducing the lighter skin tones. “People with darker skin aren’t represented in the way that they want to be,” she says, “or even in the way that’s accurate. Google has promised that the Pixel 6 camera coming out in October 2021 is going to deal with that problem,” she adds, but Beil doesn’t sound like she’s expecting much more than an incremental improvement.