In The Critic, Zareer Masani debunks a recent book’s claim that British PM Winston Churchill was responsible for the Bengal famine during the Second World War:

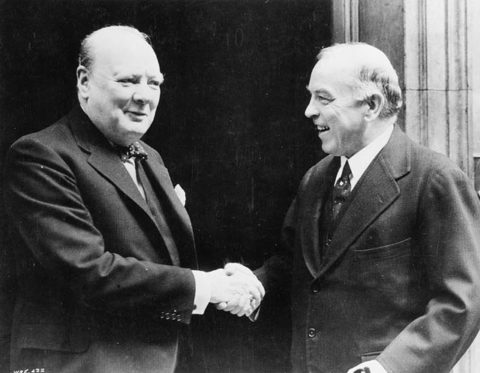

Prime Minister Winston Churchill greets Canadian PM William Lyon Mackenzie King, 1941.

Photo from Library and Archives Canada (reference number C-047565) via Wikimedia Commons.

A favourite trope of the current Black Lives Madness and its left-liberal white apologists has been the alleged infamy of Britain’s most cherished hero, Winston Churchill, charged with everything from mere racism to actual genocide. The worst accusation is that of deliberately starving four million Bengalis to death in the famine of 1943.

The famine took place at the height of World War Two, with the Japanese already occupying Burma and invading the British Indian province of Bengal, bombing its capital, Calcutta, and patrolling its coast with submarines.

The famine raged for about six months, from the summer of 1943 until the end of that year, and estimates of its victims range from half a million upwards, depending on whether one includes its indirect and long-term effects. Most famine experts agree that famines can be caused by both nature and human agency, but never by any single individual. So how has a 67-year-old British prime minister in poor health, 5,000 miles away, fighting near-annihilation in a world war, come to be charged with causing such a cataclysmic disaster?

The attempt to lay this at Churchill’s door stems from a sensationalist book by a Bengali-American journalist called Madhusree Mukerjee. As its title, Churchill’s Secret War, indicates, it was a largely conspiracist attempt to pin responsibility on distant Churchill for undoubted mistakes on the ground in Bengal.

The actual evidence shows that Churchill believed, based on the information he had been getting, that there was no food supply shortage in Bengal, but a demand problem caused by local mismanagement of the distribution system. Ironically, his view found unexpected support in a 2010 exchange between Mukerjee and the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, the world’s foremost expert on famine in India.

Commenting in the New York Times, Sen said of Mukerjee, that “she seems satisfied with little information” and that her data came from only two rice research stations, and those in only two out of 27 districts in Bengal. “The analysis I made,” countered Sen, “using data from all districts … indicated that food availability in 1943 (the famine year) was significantly higher than in 1941 (when there was no famine) … There was indeed a substantial shortfall compared with demand, hugely enhanced in a war economy … but that is quite different from a shortfall of supply compared with supply in previous years … Mukerjee seems to miss this crucial distinction, and in her single-minded … attempt to nail down Churchill, she ends up absolving British imperial policy of confusion and callousness.”