Ed Driscoll reviews the first of three volumes by Marc Cushman, relating the story behind the legendary original Star Trek TV series. Much of the first volume is apparently about the problems of getting NBC to let Gene Roddenberry back into their good graces after he humiliated the network over an earlier TV show:

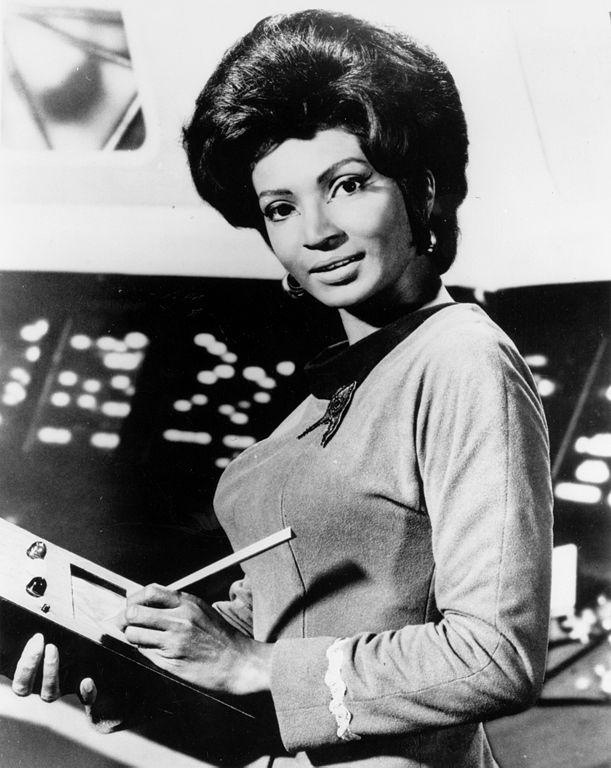

Nichelle Nichols was born in Robbins, Illinois on December 29, 1936. She played Lieutenant Uhura the Communications Officer on the U.S.S. Enterprise in the original series, Star Trek. Nichols stayed with the show and has appeared in six Star Trek movies. Her portrayal of Uhura on Star Trek marked one of the first non-stereotypical roles assigned to an African-American actress. Before joining the crew on Star Trek, she sang and danced with Duke Ellington’s band.

NASA photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Gene Roddenberry (1921-1991) was a religious agnostic and left-leaning Texan who became a WWII Army Air Force B-17 pilot, then an LA policeman who wrote numerous scripts for the burgeoning television industry in the 1950s. Eventually, he graduated to producing his own TV show in 1963, The Lieutenant, purchased by NBC and built around Gary Lockwood, the future guest star of Star Trek‘s second pilot, and the co-star of another landmark 1960s science fiction achievement, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The Lieutenant was for the most part a formulaic “military procedural” about life at Camp Pendleton, and featured numerous future Star Trek guest stars and cast members. However, Roddenberry, as was his wont, eventually decided to push the envelope, and put into production an episode on racism in the Marines called “To Set It Right,” with guest stars Dennis Hopper, future Star Trek regular Nichelle Nichols and future Trek guest star Don Marshall. The episode lost the support of the Marines, and the good will of NBC. As Roddenberry later recounted, “My problem was not the Marine Corps; it was NBC, who turned down the show flat … There was only one thing I could do, I went to the NAACP and they lowered the boom on NBC.”

As Cushman writes, this did not endear himself with NBC’s executive suit. “Roddenberry had won the battle … but lost the war. Despite satisfactory ratings, The Lieutenant was cancelled.” And NBC’s executives would not forget being hung out to dry by one of their product suppliers.

Even before The Lieutenant‘s only season of production was complete, Roddenberry began crafting a television show he called Star Trek. He had somehow stumbled into the perfect format for an hour-long network television series. While he admired shows such as Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone and its recombinant network rival The Outer Limits for their ability to comment on American society through the metaphors of science fiction and horror, these were anthology shows, introducing a new cast each week. He knew the most successful network series were those with a recurring cast, such the many westerns that aired during the 1950s and ’60s, such as the long-running Bonanza and Gunsmoke. Viewers treated these archetypal characters almost as their own family members, which in turn encouraged them to tune in each week.

Given the networks’ love of westerns in the 1960s, it’s no coincidence that Roddenberry’s first pitch to the networks used the phrase “Wagon Train to the stars” as a metaphor to describe the show. (As Cushman writes, veteran western and science fiction writer Samuel Peeples actually coined that phrase, the first of many bits of Star Trek lore that Roddenberry would eventually co-opt and take credit for.)

It’s also no coincidence that the show’s second in command was written by Roddenberry as “a mysterious female, slim and dark, expressionless, cool, one of those women who will always look the same between years 20 and 50.” As Cushman deadpans, “To be more specific: actress Majel Barrett, Roddenberry’s lover.” (Roddenberry was also having a tryst with Nichelle Nichols; she would find her way into Star Trek‘s regular cast as well.) While the pointed-eared alien Mr. Spock was also present, he was much more in the background in Roddenberry’s first draft of Star Trek.