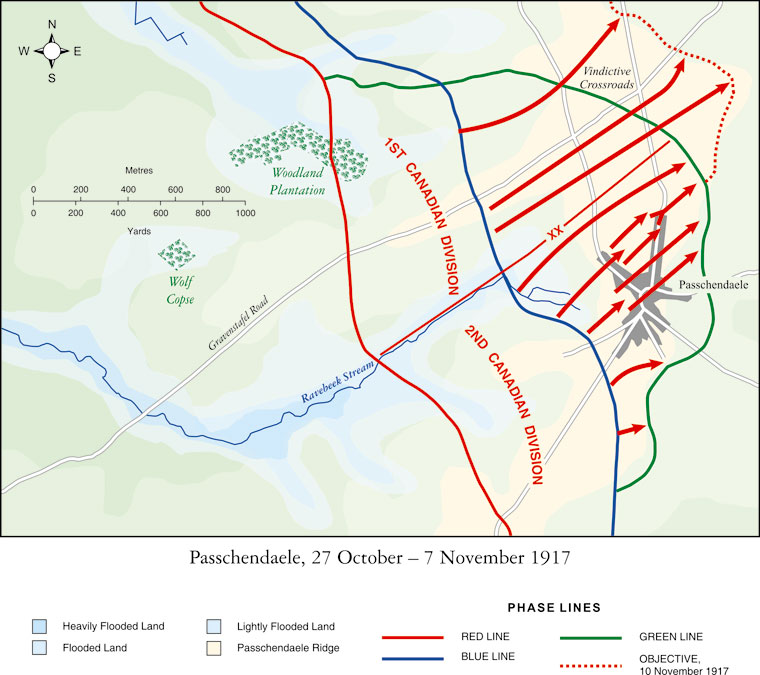

The Canadian Corps under Lieutenant General Arthur Currie began the final phase of the battle on 6 November, 1917:

By 6 November, the Canadians were prepared to advance upon the Green Line. The final objective was to capture the high ground north of the town and to secure positions on the eastern side of Passchendaele Ridge. Again, according to Major Robert Massie: “The third attack … was the day when the First and Second Divisions took Passchendaele itself. On this occasion, the attack went off the most smoothly of any of the three. They had fair ground to go over, and especially those that went into Passchendaele itself had pretty fair going, and the objectives were reached on time.”

After early hand-to-hand fighting, the 2nd Division easily occupied Passchendaele just three hours after commencement of the attack at 0600 hours. The 1st Division, however, found itself in some trouble when one company of the 3rd Battalion became cut off and was stranded in a bog. When this situation eventually righted itself, the 1st Division continued toward its objectives. Well-camouflaged tunnels at Moseelmarkt provided an opportunity for the enemy to counterattack, but they were fended off by the Canadians. By the end of the day, the Canadian Corps was firmly in control of both Passchendaele and the ridge.

The final Canadian action at Passchendaele commenced at 0605 hours on 10 November 1917. Sir Arthur Currie used the opportunity to make adjustments to the line, strengthening his defensive positions. Robert Massie summed up the thoughts of many participating Canadians as follows: “What those men did at Passchendaele was beyond praise. There was no protection in that land. They could not get into the trenches which were full of mud, and you would see two or three of them huddled together during the night, lying on ground that was pure mud, without protection of any kind, and then going forward the next morning and cleaning up their job.”

[…]

[…]

The Canadians had done the impossible. After just 14 days of combat, they had driven the German army out of Passchendaele and off the ridge. There was almost nothing left of the village to hold. Altogether, the Canadian Corps had fired a total of 1,453,056 shells, containing 40,908 tons of high explosive. Aerial photography verified approximately one million shell holes in a one square mile area. The human cost was even greater. Casualties on the British side totalled over 310,000, including approximately 36,500 Australians and 3596 New Zealanders. German casualties totalled 260,000 troops.

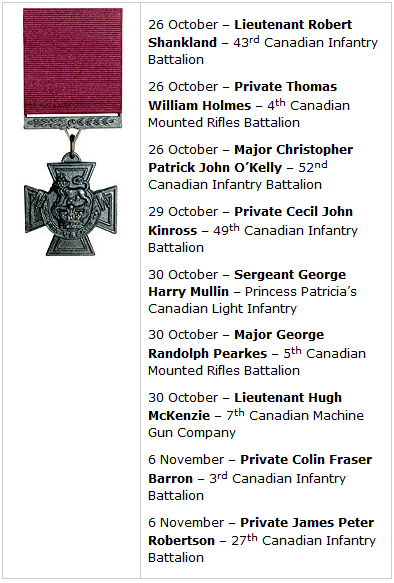

For the Canadians, Currie’s words were prophetic. He had told Haig it would cost Canada 16,000 casualties to take Passchendaele – and, in truth, the final total was 15,654, many of whom were killed. One thousand Canadian bodies were never recovered, trapped forever in the mud of Flanders. Nine Canadians won the Victoria Cross during the battles for Passchendaele. While the human cost had been terrible: “Nevertheless, the competence, confidence, and maturity began in 1915 at Ypres a short distance away, and at Vimy Ridge earlier that spring, again confirmed the reputation of the Canadian Corps as the finest fighting formation on the Western Front.” So wrote esteemed Professor of History Doctor Ronald Haycock at the Royal Military College of Canada for The Oxford Companion to Canadian History in 2004.

Haig proved to be true to his word. By 14 November 1917, the Canadians had been returned to the relative quiet of the Vimy sector. They had not been asked to hold what it had cost them so much to take. However, by March 1918, all the gains made by Canada at Passchendaele would be lost in the German spring offensive known as Operation Michael.

General Sir David Watson praised the Canadian effort: “It need hardly be a matter of surprise that the Canadians by this time had the reputation of being the best shock troops in the Allied Armies. They had been pitted against the select guards and shock troops of Germany and the Canadian superiority was proven beyond question. They had the physique, the stamina, the initiative, the confidence between officers and men (so frequently of equal standing in civilian life) and happened to have the opportunity.”

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George was even clearer when it came to the Canadians: “Whenever the Germans found the Canadian Corps coming into the line they prepared for the worst.”