Private lawyers are not needed in Germany. If you want to buy or sell a house or field, the State makes out the conveyance. If you have been swindled, the State takes up the case for you. The State marries you, insures you, will even gamble with you for a trifle.

“You get yourself born,” says the German Government to the German citizen, “we do the rest. Indoors and out of doors, in sickness and in health, in pleasure and in work, we will tell you what to do, and we will see to it that you do it. Don’t you worry yourself about anything.”

And the German doesn’t. Where there is no policeman to be found, he wanders about till he comes to a police notice posted on a wall. This he reads; then he goes and does what it says.

I remember in one German town—I forget which; it is immaterial; the incident could have happened in any — noticing an open gate leading to a garden in which a concert was being given. There was nothing to prevent anyone who chose from walking through that gate, and thus gaining admittance to the concert without paying. In fact, of the two gates quarter of a mile apart it was the more convenient. Yet of the crowds that passed, not one attempted to enter by that gate. They plodded steadily on under a blazing sun to the other gate, at which a man stood to collect the entrance money. I have seen German youngsters stand longingly by the margin of a lonely sheet of ice. They could have skated on that ice for hours, and nobody have been the wiser. The crowd and the police were at the other end, more than half a mile away, and round the corner. Nothing stopped their going on but the knowledge that they ought not. Things such as these make one pause to seriously wonder whether the Teuton be a member of the sinful human family or not. Is it not possible that these placid, gentle folk may in reality be angels, come down to earth for the sake of a glass of beer, which, as they must know, can only in Germany be obtained worth the drinking?

In Germany the country roads are lined with fruit trees. There is no voice to stay man or boy from picking and eating the fruit, except conscience. In England such a state of things would cause public indignation. Children would die of cholera by the hundred. The medical profession would be worked off its legs trying to cope with the natural results of over-indulgence in sour apples and unripe walnuts. Public opinion would demand that these fruit trees should be fenced about, and thus rendered harmless. Fruit growers, to save themselves the expense of walls and palings, would not be allowed in this manner to spread sickness and death throughout the community.

But in Germany a boy will walk for miles down a lonely road, hedged with fruit trees, to buy a pennyworth of pears in the village at the other end. To pass these unprotected fruit trees, drooping under their burden of ripe fruit, strikes the Anglo-Saxon mind as a wicked waste of opportunity, a flouting of the blessed gifts of Providence.

I do not know if it be so, but from what I have observed of the German character I should not be surprised to hear that when a man in Germany is condemned to death he is given a piece of rope, and told to go and hang himself. It would save the State much trouble and expense, and I can see that German criminal taking that piece of rope home with him, reading up carefully the police instructions, and proceeding to carry them out in his own back kitchen.

Jerome K. Jerome, Three Men on the Bummel, 1914.

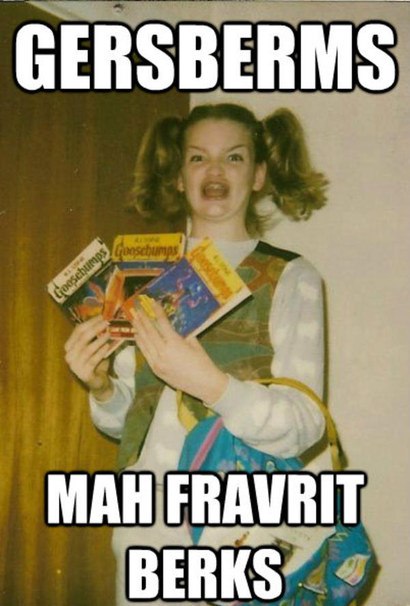

Maggie Goldenberger and her fourth- and fifth-grade pals used to amuse themselves by dressing up in weird clothes, doing crazy stuff to their hair, and posing for polaroids holding funny objects and making weird faces. Years later, Goldenberger uploaded some of her favorites to her Myspace and Facebook accounts, which led to Jeff Davis, who she didn’t know, posting it to Reddit, where a Redditor called Plantlife ganked it and captioned it with “GERSBERMS. MAH FRAVRIT BERKS” — and a meme was born.

Maggie Goldenberger and her fourth- and fifth-grade pals used to amuse themselves by dressing up in weird clothes, doing crazy stuff to their hair, and posing for polaroids holding funny objects and making weird faces. Years later, Goldenberger uploaded some of her favorites to her Myspace and Facebook accounts, which led to Jeff Davis, who she didn’t know, posting it to Reddit, where a Redditor called Plantlife ganked it and captioned it with “GERSBERMS. MAH FRAVRIT BERKS” — and a meme was born.