Russian military exercises tend to dwarf those of their neighbours, especially in the number of troops involved (and the kind of troops). Ian J. Brzezinski and Nicholas Varangis report on the phenomenon:

Exercises are used by defense establishments to test their readiness, deployability, and logistical and combat proficiency. They can be used as demonstrations of force to underscore determination to defend national territory/interests and those of allies and partners. They can also be used to intimidate and to camouflage offensive operations. Regarding the latter, in February 2014 Russia mobilized 150,000 troops under the guise of an anti-terror simulation. Many of the units in this exercise were deployed along Ukraine’s border just as Russia invaded Crimea and then later eastern Ukraine.

While military exercises are not the sole indicator of military readiness and capability, they do reflect seriousness of intent. In this case, a comparison of exercises by NATO and those of Russia reveals a troubling disparity in magnitude. In short, there is a NATO-Russia “exercise gap” that is all the more glaring when one would think it would be easier for a group of nations to orchestrate larger exercises than those conducted by a single nation.

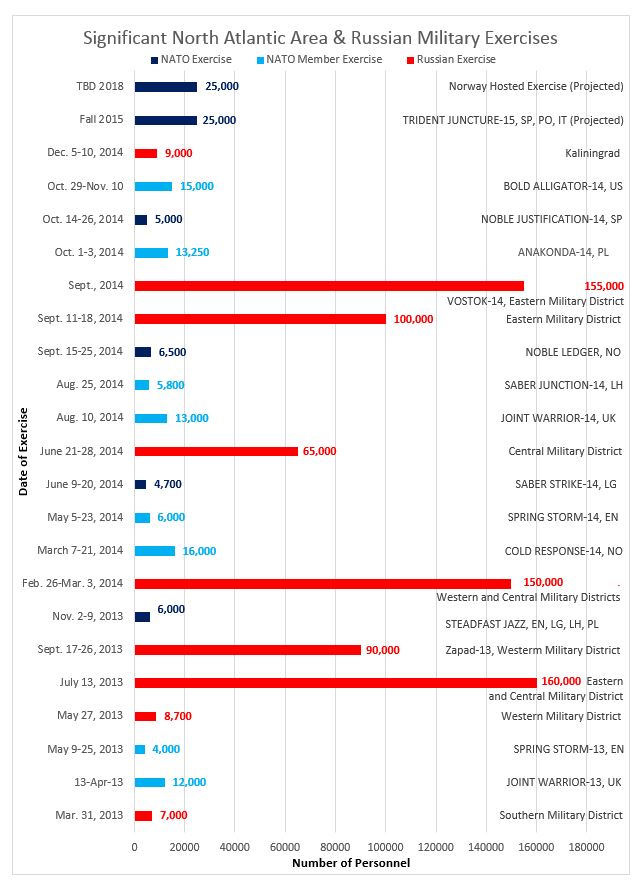

The following chart indicates that since 2013, Russia has conducted at least six military exercises involving 65,000 to 160,000 or more personnel. In contrast, during the same period, NATO’s most significant exercises included STEADFAST JAZZ, a collective defense exercise conducted in Poland and Latvia in November of 2013 involving 6,000 personnel (of which half were headquarters staff) and NOBLE LEDGER, a test of the NATO Response Force (NRF) that brought 6,500 troops to the field. Individual NATO allies have hosted larger multinational exercises in the North Atlantic Area. These include Norway’s COLD RESPONSE involving some 16,000 troops, the United States’ BOLD ALLIGATOR involving 15,000 personnel and Poland’s October 2014 ANAKONDA with 13,250 personnel.