Not having gone to university myself, I can’t speak from direct personal experience, but my strong sense is that the university degree today fulfils almost exactly the role for job-seekers that a high school diploma did about a generation ago. Most of the “entry level” jobs that actually offer some sort of career progression require no more skill or preparation now than they did 25 or 30 years ago … but the combination of lowered standards in secondary school and the vast expansion of post-secondary education have encouraged employers to filter job applicants for such openings by education first. As a direct result, parents have been pushing their children toward university as the only way to ensure those kids have a fighting chance to get into jobs that might, eventually, lead somewhere both interesting and remunerative.

But with more demand for places at university, the government is under pressure to provide funding — both to the universities to create more spaces, and to the students themselves to allow them to pay their tuition and other costs. Megan McArdle worries that pouring more money into the system isn’t the right answer:

The other day, I argued that maybe we should rethink our current policy of endlessly dumping more money into college education. It’s completely true that there is a big wage premium for having a college degree — but it does not therefore follow that we will make everyone better off by trying to shove every American through post-secondary (aka tertiary) education. We may simply be setting up college as a substitute for a high school diploma: a signal to employers that you can read and write, and are able to turn in scheduled assignments within a reasonable time frame. And in the process, excluding people who aren’t college-educated from access to decent jobs.

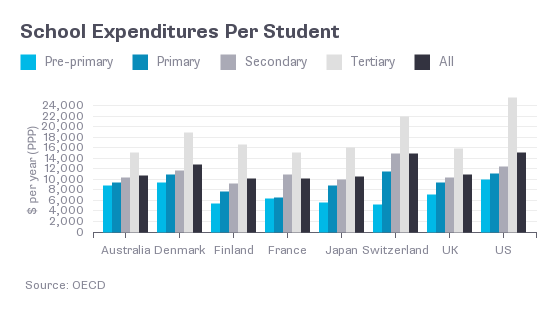

Predictably, this was not met with shouts of joy and universal admiration in all quarters. I was accused of just wanting to stick it to President Barack Obama, and also of wishing to deny the dream of college education that should be the birthright of every single American. I was also accused of being unfamiliar with the known fact that America woefully underinvests in education compared to other advanced nations.

It is true that I am unfamiliar with America’s woeful underinvestment in education, in the same way that I am unfamiliar with the tooth fairy, because both are legends with no basis in fact. American spending on education is in line with that of our peers in the developed world — a little higher than some, a little lower than others, but not really remarkable either way:

[…]

You can argue that there’s an inequality problem in our schools. In fact, I think there is obviously an inequality problem in our schools, but that the big problem is not at the college level, but rather in the primary and secondary schools that are overwhelmingly government-funded. And those disparities are also not primarily about the dollar amounts going into schools — Detroit spends well above the U.S. average per pupil, and yet one study found that half the population of the city was “functionally illiterate.”

Should we fix the issues with those schools? Absolutely — and doing so might mean spending more money. But that doesn’t mean that we need to increase the overall level of educational funding. It means that we need to identify ways to improve those underperforming schools, then find out how much more it would cost to implement those programs. It is just as likely that improvements will come from changing methods and reallocating resources as that they will require us to pour more money into failing institutions.