In Forbes, Trevor Butterworth looks at an odd data analysis piece where the “fix” for a discrepancy in reported drinks per capita is to just assume everyone under-reported and to double that number:

“Think you drink a lot? This chart will tell you.”

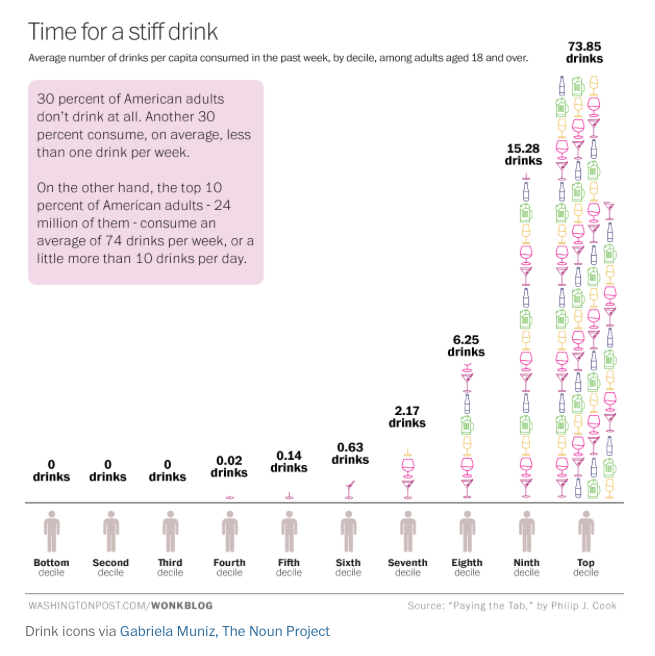

The chart, reproduced below breaks down the distribution of drinkers into deciles, and ends with the startling conclusion that 24 million American adults — 10 percent of the adult population over 18 — consume a staggering 74 drinks a week.

The source for this figure is “Paying the Tab,” by Phillip J. Cook, which was published in 2007. If we look at the section where he arrives at this calculation, and go to the footnote, we find that he used data from 2001-2002 from NESARC, the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, which had a representative sample of 43,093 adults over the age of 18. But following this footnote, we find that Cook corrected these data for under-reporting by multiplying the number of drinks each respondent claimed they had drunk by 1.97 in order to comport with the previous year’s sales data for alcohol in the US. Why? It turns out that alcohol sales in the US in 2000 were double what NESARC’s respondents — a nationally representative sample, remember — claimed to have drunk.

While the mills of US dietary research rely on the great National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey to digest our diets and come up with numbers, we know, thanks to the recent work of Edward Archer, that recall-based survey data are highly unreliable: we misremember what we ate, we misjudge by how much; we lie. Were we to live on what we tell academics we eat, life for almost two thirds of Americans would be biologically implausible.

But Cook, who is trying to show that distribution is uneven, ends up trying to solve an apparent recall problem by creating an aggregate multiplier to plug the sales data gap. And the problem is that this requires us to believe that every drinker misremembered by a factor of almost two. This might not much of a stretch for moderate drinkers; but did everyone who drank, say, four or eight drinks per week systematically forget that they actually had eight or sixteen? That seems like a stretch.

We are also required to believe that just as those who drank consumed significantly more than they were willing to admit, those who claimed to be consistently teetotal never touched a drop. And, we must also forget that those who aren’t supposed to be drinking at all are also younger than 18, and their absence from Cook’s data may well constitute a greater error.