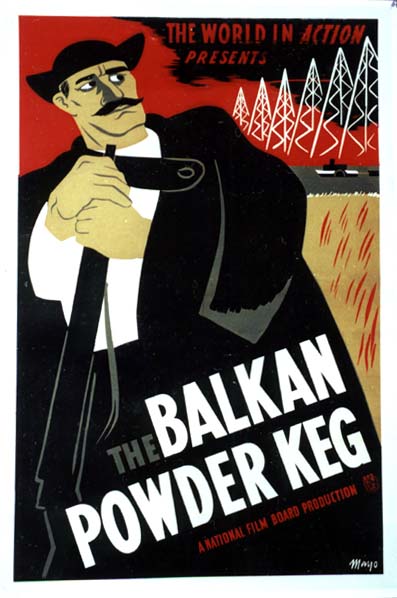

The “Balkan powder keg”. Is there a more over-used description from writers trying to describe the origins of World War One? Like most clichés, there’s more than just a hint of truth to it. Part eight of this (long, long) series discussed the start of a series of “small wars” that ended up being very significant as escalators leading towards the beginning of the Great War. You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, part seven and part eight. The Balkans are picturesque as heck, a tangled mass of ethnic, religious, and national interests, and a ready source of trouble for the rest of Europe. But right up to the end of July, 1914, most sensible people thought the most recent set of troubles would be resolved soon. After all, this was the age of reason, and nobody wanted to go to war over silly tribal differences…

The “Balkan powder keg”. Is there a more over-used description from writers trying to describe the origins of World War One? Like most clichés, there’s more than just a hint of truth to it. Part eight of this (long, long) series discussed the start of a series of “small wars” that ended up being very significant as escalators leading towards the beginning of the Great War. You can catch up on the earlier posts in this series here: part one, part two, part three, part four, part five, part six, part seven and part eight. The Balkans are picturesque as heck, a tangled mass of ethnic, religious, and national interests, and a ready source of trouble for the rest of Europe. But right up to the end of July, 1914, most sensible people thought the most recent set of troubles would be resolved soon. After all, this was the age of reason, and nobody wanted to go to war over silly tribal differences…

Second Balkan War – The falling-out of the thieves

Shortly after the amazing success of the Balkan League’s fight against the Ottoman Empire, the victorious Balkan powers fell out over the spoils and went at it again, this time redrawing the borders to Bulgaria’s severe disadvantage (thanks in part to Romania joining in the fun). The war wasn’t inevitable, but the seeds were planted almost from the start of the fighting during the First Balkan War: secret agreements between the League allies to partition the yet-to-be-conquered lands were rapidly made obsolete by the facts on the ground: Serbia and Greece faced weaker opposition and therefore took lands promised beforehand to Bulgaria. Bulgaria anticipated its allies would live up to the terms of their agreements, but both Serbia and Greece coveted the territory each had gained (that had been secretly promised to Bulgaria before hostilities commenced) more than they valued the continued goodwill of the Bulgarians.

Having active grievances — and much more significantly, an active and recently victorious army — the Bulgarians decided to take by force what their former allies were denying them diplomatically. Unfortunately for Bulgaria, the Greeks and Serbians also had active and recently victorious armies … and the advantage of already occupying the disputed territories. In addition, the Ottoman Empire noticed a great opportunity to rectify some of the unfortunate mistakes made during the first war, and joined in the melee. Perhaps even more importantly, the Rumanians noticed that they had a golden-but-fleeting chance to re-arrange their border with Bulgaria in a more pleasing fashion, and also entered the lists.

Given the forces aligned against Bulgaria, it should be no surprise that despite having the advantage of launching the initial attacks, the end results (as documented in the August 1913 Treaty of Bucharest and the September 1913 Treaty of Constantinople) were not what Bulgarian leaders had hoped for.

Bulgarian defeat at the hands of the Serbs and the other powers was not pre-ordained: the one thing that could have changed the course of the Balkan Wars was the direct intervention of Russia. Both Bulgaria and Serbia were clients of the string-pullers in St. Petersburg, but at some point the Russians had to make a clear choice between their “little brothers” in Sofia or those in Belgrade. In The Sleepwalkers, Christopher Clark describes that point of decision:

There was one strategic choice that Sazonov and his colleagues would eventually be forced to confront. Should Russia support Bulgaria or Serbia? Of the two countries, Bulgaria was clearly the more strategically important. Its location on the Black Sea and Bosphorus coasts made it an important partner. The defeat of Ottoman forces in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-8 had created the conditions for the emergence, under Russian custodianship, of a self-governing Bulgarian state under the nominal suzerainty of the Ottoman Porte. Bulgaria was thus historically a client state of St. Petersburg. But Sofia never became the obedient satellite that the Russians had wished for. Russophile and “western” political factions competed for control of foreign policy (as indeed they still do today) and the leadership exploited the country’s strategically sensitive location by transferring their allegiances from one power to another.

[…]

In March 1910, delegations from Sofia and Belgrade visited St. Petersburg within two weeks of each other for high-level talks. The Bulgarians pressed their Russian interlocutors to abandon Serbia and commit clearly to Sofia — only on this basis would a stable coalition of Balkan states emerge. It was impossible, the Bulgarian premier Malinov told Izvolsky, for the Russians to create a Great Bulgaria and a Great Serbia at the same time:

Once you decide to go with us for the sake of your own interests, we will easily settle the Macedonian question with the Serbs. As soon as this is understood in Belgrade — and you must make it clear in order to be understood — the Serbs will become more conciliatory.

The Serbs, however, were more successful in securing Russian support for their aims. Alexander Izvolsky (the Russian Foreign Minister) assured King Peter that, when push came to shove, Serbia enjoyed Russia’s complete confidence and support. This had the temporary advantages of satisfying the Serbs and the Russian domestic press: although the decision was not formally announced, the press were pushing continuously for Russian support for Serbia and the Russian government understood the strength of this opinion among the rising Russian middle class (small, but influential).

As we get closer to the actual outbreak of World War One, the individual conflicts and events gain a greater share of the attention: what might have been a minor issue a few years earlier now attracted the interest and (sometimes) the involvement of the great powers, who in turn were finding it harder to stay aloof from “trivia”. Russia’s deliberate pot-stirring in the Balkans may at the time have seemed a cheap and easy way to divert press attention away from legitimate domestic issues and onto “safer” foreign concerns. But such activities had a way of perpetuating themselves, and Russia of all the great powers, could least afford to risk its remaining prestige in battles and disputes well beyond the reach of their own military power. The easy option of making the Balkans seem more important lead to the understanding among the “chattering classes” of Moscow and St. Petersburg that any setback to Serbian aspirations somehow directly affronted Russia and therefore required direct Russian involvement.

An easy way to redirect the newspapers to foreign affairs somehow became a lever with which Serbian extremists could move Russia (against her own best interests) into positions of confrontation with Austria (and Germany). I’m not trying to imply that editorial writers in Russia controlled Russian foreign policy, but that the evidence is that after the 1905 revolution, Russian leaders were dangerously aware of and willing to risk much to channel the power of the press (but lacked the skill to do so in ways that were not in the end catastrophic).