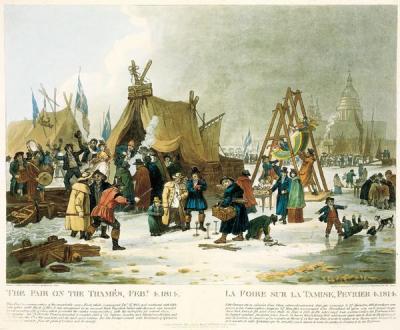

The famous river doesn’t freeze as it did during the Little Ice Age, so the very last Frost Fair was held in 1814:

It is 200 years ago since the last “frost fair” — an impromptu festival on a frozen Thames, complete with dancing, skittles and temporary pubs. Could such hedonism be repeated today?Londoners stood on the Thames eating gingerbread and sipping gin. The party on the frozen river had begun on 1 February and would carry on for another four days.

The ice was thick enough to support printing presses churning out souvenirs. Oxen were roasted in front of roaring fires, drink was liberally taken and dances were held. An elephant was marched across the river alongside Blackfriars Bridge.

It was February 1814. George III was on the throne, Lord Liverpool was prime minister and the Napoleonic wars would soon be won.

People didn’t know it then but this “frost fair” — a cross between a Christmas market, circus and illegal rave — would be the last. In the 200 years that have elapsed since, the Thames has never frozen solid enough for such hedonism to be repeated.

But between 1309 and 1814, the Thames froze at least 23 times and on five of these occasions — 1683-4, 1716, 1739-40, 1789 and 1814 — the ice was thick enough to hold a fair.

Update: Over lunch, I was reading Correlli Barnett’s Marlborough and came across this description of the onset of winter in 1708-09 (and a frost fair that the BBC didn’t list):

And for Europe too the coming of a Whig administration in England was a fateful event. The Whig leaders were hot for the exaction from Louis XIV of ‘no peace without Spain – entire’, without any compromise whatsoever. Yet in the winter and spring of 1709 even such inflated war aims began to look practicable. Before the Duke at last closed down the Oudenarde campaign in January 1709, long after the normal time for going into winter quarters, he had retaken Bruges and Ghent. And the siege of Ghent witnessed the onset of an enemy even more terrible to France than Marlborough. In the last days of 1708 cold of unimagined bitterness closed on Europe like a trap. At Ghent the sentinels of besieged and besieging forces alike were frozen to death at their posts. And this was only a beginning: after a short and deceptive thaw in January, the cold set in like another ice age, the people of Europe cringing month after month under a bruise-coloured sky heavy with snow. On the frozen Thames at London Bridge there was an ice fair; a little city of booths and stalls stretching from bank to bank, and bonfires twinkling across the ice in the polar gloom. From Brussels Marlborough was reporting to Heinsius in February:

The continuall snow as well as hard frost will, if it continues, kill al the cattel of this country and bee very inconvenient for our garrisons, for even in this town we have no forage but what we bring dayly by carts …

The port of Harwich was ice bound; so were the Dutch ports. There were ice floes in the Channel. Even the mouth of the Tagus at Lisbon was frozen. It was fortunate indeed that the Duke had not carried out his post-Oudenarde plan to invade France, or his army might now have been lying somewhere between Abbeville and Paris, with seaborne supplies cut off by ice, and dependent for subsistence on what it could find in the French countryside.

And in France, already impoverished by war as she was, famine had come in the wake of frost. The cattle died; the vines split. In the towns and the country the starving wandered in search of food in ragged, despairing packs. The very fabric of French society seemed in peril from the effects of the cold.