BBC Archive

Published 5 Mar 2023“The ration book has done its job. It’s been a long job. Indeed, children up to school-leaving age have never known life without the ration book.”

On the fourth of July, the rationing of meat in Britain came to an end, the final step in dismantling Britain’s whole wartime system of food distribution. After fourteen long years, Britons can at last tear up their ration books.

Richard Baker looks back at some of the key moments in the story of rationing and de-rationing.

Originally broadcast 5 July, 1954.

June 8, 2023

1954: The END of RATIONING

May 26, 2023

CH-124 Sea King; Legendary ASW helicopter and example of a deeply flawed defense procurement process

Polyus

Published 21 May 2023The Sea King was a legendary aircraft in the history of the Royal Canadian Navy. It filled the role of hunter and killer in the Cold War against Soviet submarines. By the mid-90s the situation had changed and their retirement seemed eminent. How naive. The process of finding a replacement for this workhorse would be an election promise by government after government for over 30 years. Its replacement, the CH-148 Cyclone, became operational in 2018. This allowed the 55 year old workhorses to finally retire.

(more…)

May 7, 2023

Tank Chats Reloaded | S-Tank | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 27 Jan 2023In this episode of Tank Chats Reloaded, we are delighted to be joined by Stefan Karlsson, the director and curator of The Swedish Tank Museum. He shares his remarkable journey with the S-Tank, from his first experience driving it at the age of nine, to his later service in the Swedish Army. Stefan’s passion for the S-Tank is evident, and his story is sure to captivate and inspire.

(more…)

April 26, 2023

Tanks Chats #169 | Scimitar Mark 1 & Scimitar Mark 2 | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 20 Jan 2023In this week’s video, David Willey continues David Fletcher’s CVRT Tank Chats series, delving into the fascinating history of the Scimitar Mark 1 & Scimitar Mark 2. David provides an in-depth look at the development of these two iconic tracked vehicles, exploring their unique features and capabilities. He also examines how they have evolved over the years, and been used in various military operations.

(more…)

April 4, 2023

Tank Chats Reloaded | Challenger 1 | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 16 Dec 2022In the first episode of Tank Chats Reloaded we hear from Major General Patrick Cordingley who both commanded Challenger 1 during the First Gulf War and was involved in its design. Also introducing our new presenter Chris Copson, host of the new Tank Chats Reloaded series — where we’ll be revisiting old favourites from Tank Chats.

(more…)

April 2, 2023

QotD: The (in-)effectiveness of chemical weapons against “Modern System” armies

… it is far easier to protect against chemical munitions than against an equivalent amount of high explosives, a point made by Matthew Meselson. Let’s unpack that, because I think folks generally have an unrealistic assessment of the power of a chemical weapon attack, imagining tiny amounts to be capable of producing mass casualties. Now chemical munition agents have a wide range of lethalities and concentrations, but let’s use Sarin – one of the more lethal common agents, as an example. Sarin gas is an extremely lethal agent, evaporating rapidly into the air from a liquid form. It has an LD50 (the dose at which half of humans in contact will be killed) of less than 40mg per cubic meter (over 2 minutes of exposure) for a human. Dangerous stuff – as a nerve agent, one of the more lethal chemical munitions; for comparison it is something like 30 times more lethal than mustard gas.

But let’s put that in a real-world context. Five Japanese doomsday cultists used about five liters of sarin in a terror attack on a Tokyo Subway in 1995, deployed, in this case, in a contained area, packed full to the brim with people – a potential worst-case (from our point of view; “best” case from the attackers point of view) situation. But the attack killed only 12 people and injured about a thousand. Those are tragic, horrible numbers to be sure – but statistically insignificant in a battlefield situation. And no army could count on ever being given the kind of high-vulnerability environment like a subway station in an actual war.

In order to produce mass casualties in battlefield conditions, a chemical attacker has to deploy tons – and I mean that word literally – of this stuff. Chemical weapons barrages in the First World War involved thousands and tens of thousands of shells – and still didn’t produce a high fatality rate (though the deaths that did occur were terrible). But once you are talking about producing tens of thousands of tons of this stuff and distributing it to front-line combat units in the event of a war, you have introduced all sorts of other problems. One of the biggest is shelf-life: most nerve gasses (which tend to have very high lethality) are not only very expensive to produce in quantity, they have very short shelf-lives. The other option is mustard gas – cheaper, with a long shelf-life, but required in vast quantities (during WWII, when just about every power stockpiled the stuff, the stockpiles were typically in the many tens of thousands of tons range, to give a sense of how much it was thought would be required – and then think about delivering those munitions).

[…]

But that’s not the only problem – the other problem is doctrine. Remember that the modern system is all about fast movement. I don’t want to get too deep into maneuver-warfare doctrine (one of these days!) but in most of its modern forms (e.g. AirLand Battle, Deep Battle, etc) it aims to avoid the stalemate of static warfare by accelerating the tempo of the battle beyond the defender’s ability to cope with, eventually (it is hoped) leading the front to decompose as command and control breaks down.

And chemical weapons are just not great for this. Active use of chemical weapons – even by your own side – poses all sorts of issues to an army that is trying to move fast and break things. This problem actually emerged back in WWI: even if your chemical attack breaks the enemy front lines, the residue of the attack is now an obstruction for you. […] A modern system army, even if it is on the defensive operationally, is going to want to make a lot of tactical offensives (counterattacks, spoiling attacks). Turning the battle into a slow-moving mush of long-lasting chemical munitions (like mustard gas!) is counterproductive.

But that leaves the fast-dispersing nerve agents, like sarin. Which are very expensive, hard to store, hard to provision in quantity and – oh yes – still less effective than high explosives when facing another expensive, modern system army, which is likely to be very well protected against such munitions (for instance, most modern armored vehicles are designed to be functionally immune to chemical munitions assuming they are buttoned up).

This impression is borne out by the history of chemical weapons; for top-tier armies, just over a century of being a solution in search of a problem. The stalemate of WWI produced a frantic search for solutions – far from being stupidly complacent (as is often the pop-history version of WWI), many commanders were desperately searching for something, anything to break the bloody stalemate and restore mobility. We tend to remember the successful innovations – armor, infiltration tactics, airpower – because they shape subsequent warfare. But at the time, there were a host of efforts: highly planned bite-and-hold assaults, drawn out brutal et continu efforts, dirigibles, mining and sapping, ultra-massive artillery barrages (trying a wide variety of shell-types and weights). And, of course, gas. Gas sits in the second category: one more innovation which failed to break the trench stalemate. In the end, even in WWI, it wasn’t any more effective than an equivalent amount of high explosives (as the relative casualty figures attest). Tanks and infiltration tactics – that is to say, the modern system – succeeded where gas failed, in breaking the trench stalemate, with its superiority at the role demonstrated vividly in WWII.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Why Don’t We Use Chemical Weapons Anymore?”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-03-20.

March 13, 2023

1949: HMS Implacable‘s Last Voyage | BBC Television Newsreel | Retro Transport | BBC Archive

BBC Archive

Published 19 Nov 2022HMS Implacable, a 149 year-old ship of the line — which survived the Battle of Trafalgar — embarks on her final, solemn voyage.

The figurehead, deck and stern cabin of this captured French ship are to be kept at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, but her hulk is to be towed out from Portsmouth dockyard and scuttled.

Originally broadcast 5 December, 1949.

(more…)

March 10, 2023

Tank Chats #168 | Vixen & Fox | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 18 Nov 2022Join David Fletcher as he takes a look at the Vixen and Fox armoured cars.

(more…)

March 9, 2023

Look at Life – The Cherry Pickers (1965)

PauliosVids

Published 20 Nov 2018Following the 11th Hussars from Hanover to Coburg.

February 17, 2023

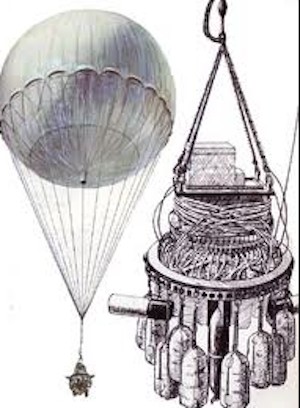

Spy ballooning has a remarkably long history (that’s clearly still ongoing)

In The Line, Scott Van Wynsberghe outlines the history of balloons in wartime and (as many are now aware from recent events) in peacetime:

China’s balloon spying is shocking on so many levels that you can take your pick. There is the ultra-flagrant violation of foreign sovereignty, the stunningly surreal air of denial exhibited by Beijing, and the fearful sense that something in the world order just lurched. There is also puzzlement: what, balloon spying is still a thing? Indeed it is, and its centuries-long history is instructive as to what China is now doing. It also makes clear that the U.S. is no innocent victim here but rather a past offender with a cleaned-up act.

Among the first major studies of aerial reconnaissance was a book brought out by military author Glenn B. Infield way back in 1970. In a way, Infield was charting unknown territory. When he addressed balloons in particular, he traced their use in spying to the many wars associated with the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic eras. In 1794, he related, the French military officer Jean-Marie-Joseph Countelle made an ascent at the city of Maubeuge in order to monitor enemy forces in the area. In the process, Countelle became the first balloon spy.

As technology improved, other firsts followed. By the 1850s, cameras were mounted on French military balloons. In the 1860s, during the American Civil War, Union forces battling the Confederacy used balloons trailing telegraphic wires, which transmitted immediate updates from the balloonists. Yet technology cut both ways. By the early 1900s, balloons had a nemesis in sight, in the form of winged and powered aircraft.

The inevitable showdown occurred in the First World War, and it was ugly. Large numbers of observation balloons were used by all sides in the conflict, and WWI historian Denis Winter claims the Germans alone deployed 170 of them in France by 1917. Typically, such balloons were tethered in place near the frontline, floating at several thousand feet, with telephone wires dangling to the ground. Although they seemed vulnerable, they were actually protected from below by anti-aircraft units, which blasted at any enemy plane that got too close. However, the reverse was also true, with balloons themselves being fired at from the ground. By 1915, says aviation writer Ralph Barker, the British were losing at least a dozen balloons a month from all forms of enemy action. Those balloonists who were not shot to pieces often had to bail out, putting their faith in parachutes that did not always work. (Horrified onlookers called them “balloonatics.”) The fighter pilots responsible for much of this mayhem — which they called “balloon-busting” — may not have had an easy time, but some of them scored heavily, with one Frenchman named Coiffard tallying 28 balloons. Although observation balloons managed to make it to the end of the war, it was a near-run thing. According to author Linda Hervieux, nobody after the war was talking about repeating that experience in any future fighting.

[…]

Once the Second World War was underway, some propaganda leafleting did occur, but secret balloon activity seemed to be at a low level. That was very misleading, because one of the tensest moments in ballooning history was playing out in the background, but it occurred amid so much security that the entire tale took years to emerge. In 1944, Japan launched the first of over 9,000 bomb-rigged balloons across the Pacific. Robert C. Mikesh, in a comprehensive 1973 monograph issued by the Smithsonian Institution, noted that almost a thousand of the balloons may have reached North America, but the true number is unknowable, because so many came down in remote wilderness. (One was found by forestry workers in British Columbia as late as 2014.) Mikesh tabulated 285 known incidents, ranging from Alaska all the way south to Baja California and as far inland as Manitoba. Both the U.S. and Canada clamped down hard on any news about the balloons, for fear of providing Tokyo valuable feedback about the results of the campaign. (In other words, balloon counterintelligence became a priority.) In general, the balloons did not cause a lot of harm, but one of them slaughtered six people in Oregon in 1945. By a strange fluke, one of the few groups in the U.S. that knew the full story of the balloons was an element of the Black community. The all-Black 555th Parachute Infantry Battalion was sent to the U.S. West to handle emergencies caused by the balloons.

The remains of a Japanese balloon bomb found in the Monashee Mountains near Lumby, BC in 2014. It was detonated on-site by the bomb disposal unit of Maritime Forces Pacific of the Royal Canadian Navy.

There is a strong temptation to blame the Japanese balloon bombs for what happened next, because the U.S. unaccountably entered the Cold War as the most pugnacious exponent of clandestine ballooning up to that time. Whatever the explanation, the epic struggle between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics plunged U.S. ballooning into a tangle of psychological warfare, shadowy science, under-the-table finances, and clandestine belligerence indistinguishable from military attacks. Plus, UFOs and breakfast foods were involved (seriously).

February 12, 2023

Avro Vulcan: What made the Vulcan the best V bomber?

Imperial War Museums

Published 28 Apr 2021The Avro Vulcan Bomber, the most famous of the British V bombers, is known for its distinctive howl and delta wing. Initially one of the delivery agents of Britain’s independent nuclear deterrent during the Cold War, the Vulcan later fulfilled another role, undertaking the longest bombing raid in history for Operation Black Buck in the Falklands Campaign of 1982. One of the first operational RAF aircraft with a delta wing, this impressive Cold War jet has never lost its appeal. In this video, events and experiences coordinator Liam Shaw takes us through the extraordinary history and technological achievements of the Avro Vulcan. We go into the cockpit and hear first-hand from the people who flew this unique machine throughout its long and remarkable history.

(more…)

February 2, 2023

MAC Model 1947 Prototype SMGs

Forgotten Weapons

Published 12 Oct 2022Immediately upon the liberation of France in 1944, the French military began a process of developing a whole new suite of small arms. As it applied to SMGs, the desire was for a design in 9mm Parabellum (no more 7.65mm French Long), with an emphasis on something light, handy, and foldable. All three of the French state arsenals (MAC, MAS, and MAT) developed designs to meet the requirement, and today we are looking at the first pair of offerings from Chatellerault (MAC). These are the 1947 pattern, a very light lever-delayed system with (frankly) terrible ergonomics.

Many thanks to the French IRCGN (Criminal Research Institute of the National Gendarmerie) for generously giving me access to film these unique specimens for you!

Today’s video — and many others — have been made possible in part by my friend Shéhérazade (Shazzi) Samimi-Hoflack. She is a real estate agent in Paris who specializes in working with English-speakers, and she has helped me arrange places to stay while I’m filming in France. I know that exchange rates make this a good time for Americans to invest in Europe, and if you are interested in Parisian real estate I would highly recommend her. She can be reached at: samimiconsulting@gmail.com

(Note: she did not pay for this endorsement)

(more…)

February 1, 2023

What’s the Greatest Machine of the 1980s … the FV107 Scimitar?

Engine Porn

Published 19 Jan 2015Light, agile and very fast on all types of terrain, the fabulous Scimitar FV107 armoured reconnaissance vehicle was developed by car manufacturer Alvis, who were asked to build a fast military vehicle that was light enough to be airdropped — simply not an option for full sized battle tanks at the time, which averaged around 13 tonnes. [NR: I think they mean “light tanks” here, as MBTs of the era would have been more like 50+ tons.]

Alvis got the weight down to under 8 tonnes by using a new type of aluminium alloy and minimising armour rating in favour of speed. They built the Scimitar around a 220 horsepower, six cylinder, 4.2 litre Jaguar sports car engine with ground-breaking transmission that allowed differential power to each set of tracks. The result was a sports car of the the military world that might not be the toughest in the field, but could race its way out of trouble at speeds of up to 70 miles an hour.

What makes it great: A revolutionary armoured vehicle that brought the very best of British sports car performance to the battlefield.

Time Warp: The Scimitar was the only armoured vehicle to be used by the British Army in the Falklands War.

This short film features Chris Barrie taking the Scimitar for a spin.

(more…)

January 27, 2023

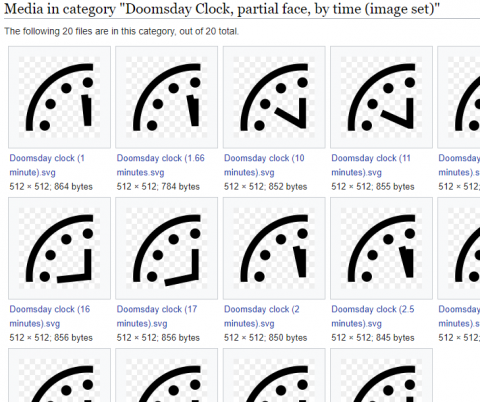

The return of the revenge of the bride of the Doomsday Clock

It’s amazing how much free publicity you can get by pulling out the hoary old Cold War propaganda tools, as Andrew Potter explains with the re-re-re-introduction of the Doomsday Clock bullshit:

Earlier this week, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved the hands of its Doomsday Clock ahead by ten seconds, to 90 seconds to midnight. This is the closest the clock has ever been to midnight, and, according to the press release announcing the move: “Never in the Doomsday Clock’s 76-year history have we been so close to global catastrophe.”

If you’re under, say, 40 years of age or so, that paragraph is probably pure gobbledygook, the written equivalent of the squawk of a 2400 baud modem going through its handshaking protocols. But for those of us in the ever-dwindling cohorts of Gen-Xers and Baby Boomers, hearing about the movement of the Doomsday Clock is to be jerked back into a time marked by both profound moral clarity and deep existential anxiety.

A bit of background on the Doomsday Clock might help. It was a creature of the Cold War, founded in 1947 by some of the scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project to raise public awareness of the threat of nuclear weapons. As the Bulletin puts it, the clock uses “the imagery of apocalypse (midnight) and the contemporary idiom of nuclear explosion (countdown to zero) to convey threats to humanity and the planet”. The decision to move or leave the minute hand of the Clock in place is made each year by the various trustees of the Bulletin, based on their evaluation of the world’s vulnerability to catastrophe.

The clock was initially set at a nice and relaxed seven minutes to midnight, and over the following few decades it was moved closer in response to clear nuclear threats, things like ramped-up testing of new bombs, nuclear proliferation, or rising Cold War tensions. During periods of detente or after the signing of arms reductions treaties, the minute hand would retreat. In 1991, it was moved back to 17 minutes to midnight after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

For most of the second half of the 20th century, the Doomsday Clock was a healthy reminder of the most salient geopolitical fact of the era, which is that two superpowers were pointing thousands of nuclear weapons at one another.

But like many Cold War relics, the demise of the U.S.S.R. left it scrambling for a raison d’etre. In a bit of clever PR entrepreneurialism, the executive of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists turned the clock into a more generalized warning against war, climate change and other ecological or technological threats. The nadir of this shift in mission came on January 23rd 2020, when the Bulletin moved the clock’s hands to 100 seconds to midnight.

As the press release accompanying the ticking of the clock noted at the time, this put humanity “closer than ever” to catastrophe. Given that the clock had kept watch over our drive for self-destruction through the Suez Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the sabre-rattling Reagan administration, and the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, it makes one wonder just what happened in early 2020 to merit such a fearful move.

January 26, 2023

Tank Chats #165 | Striker | The Tank Museum

The Tank Museum

Published 30 Sept 2022In this weeks video, David Fletcher discusses the development and features of Striker, another vehicle from the CVRT family.

(more…)