The Tank Museum

Published 2 Jun 2023In this video, Chris Copson looks at the Swingfire, a Cold War period anti-tank guided weapons system. This powerful and hard-hitting missile was mounted on vehicles including Striker, Ferret, and FV 432. With a range of up to 4km, it had the significant advantage that it would outrange tank guns and could be fired remotely by the controller, enabling the launch vehicle to remain in cover.

(more…)

September 20, 2023

Wire Guided Tank Killer | Swingfire | Anti-Tank Chats

September 18, 2023

BM59: The Italian M14

Forgotten Weapons

Published 25 Oct 2017After World War Two, both the Beretta and Breda companies in Italy began manufacturing M1 Garand rifles. When Italy decided that they wanted a more modern selective-fire, magazine-fed rifle, they chose to adapt the M1 Garand to that end rather than develop a brand new rifle. Two Beretta engineers, Vittorio Valle and Domenico Salza, began work in 1957 on what would become the BM-59. Prototypes were ready in 1959, trials were run in 1960, and by 1962 the new weapon was in Italian military hands.

The BM59 is basically an M1 Garand action and fire control system, but modernized. The caliber was changed to 7.62mm NATO, and the barrel shortened to 19.3 inches. A simple but effective selective fire system was added to the fire control mechanism, and the en bloc clips replaced with a 20-round box magazine (and stripper clip loading guide to match). A folding integral bipod was added to allow the rifle to be used for supporting fire on full auto, and a long muzzle device was added along with a gas cutoff and grenade launching sight to allow the use of NATO standard 22mm rifle grenades.

In this form, the BM59 was a relative quickly developed and quite successful and well-liked rifle. In addition to the Italian military, it was purchased by Argentina, Algeria, Nigeria, and Indonesia. A semiautomatic version was made for the US commercial market and designated the BM62, and a small number of fully automatic BM-59 rifles — like the one in this video — were imported into the US before the 1968 Gun Control Act cut off importation of foreign machine guns.

(more…)

September 16, 2023

France’s Vietnam War: Fighting Ho Chi Minh before the US

Real Time History

Published 15 Sept 2023After the Second World War multiple French colonies were pushing towards independence, among them Indochina. The Viet Minh movement under Ho Chi Minh was clashing with French aspirations to save their crumbling Empire.

(more…)

August 27, 2023

6 Strange Facts About the Cold War

Decades

Published 27 Jul 2022Welcome to our history channel, run by those with a real passion for history & that’s about it. In today’s video, we will be exploring 6 odd Cold War facts.

(more…)

August 25, 2023

The German Democratic Republic, aka East Germany

Ed West visited East Berlin as a child and came away unimpressed with the grey, impoverished half of Berlin compared to “the gigantic toy shop that was West Berlin”. The East German state was controlled by the few survivors of the pre-WW2 Communist leaders who fled to the Soviet Union:

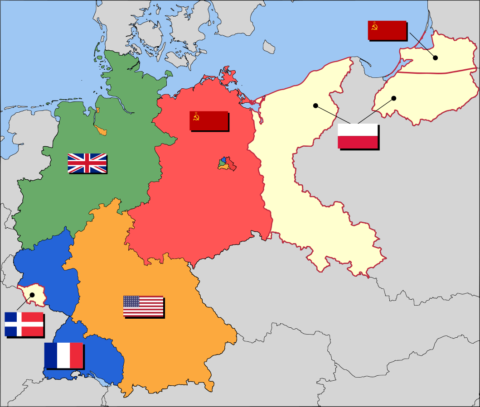

Occupation zone borders in Germany, 1947. The territories east of the Oder-Neisse line, under Polish and Soviet administration/annexation, are shown in cream as is the likewise detached Saar protectorate. Berlin is the multinational area within the Soviet zone.

Image based on map data of the IEG-Maps project (Andreas Kunz, B. Johnen and Joachim Robert Moeschl: University of Mainz) – www.ieg-maps.uni-mainz.de, via Wikimedia Commons.

In my childish mind there was perhaps a sense that East Germany, the evil side, was in some way the spiritual successor both to Prussia and the Third Reich – authoritarian, militaristic and hostile. Even the film Top Secret, one of the many Zucker, Abrahams and Zucker comedies we used to enjoy as children, deliberately confused the two, the American rock star stuck in communist East Germany then getting caught up with the French resistance. The film showed a land of Olympic female shot put winners with six o’clock shadows, crappy little cars you had to wait a decade for, and a terrifying wall to keep the prisoners in – and compared to the gigantic toy shop that was West Berlin, I was not sold.

I suppose that’s how the country is largely remembered in the British imagination, a land of border fences and spying, The Lives of Others and Goodbye Lenin. When the British aren’t comparing everything to Nazi Germany, they occasionally stray out into other historic analogies by comparing things to East Germany, not surprising in a surveillance state such as ours (these rather dubious comparisons obviously intensified under lockdown).

This is no doubt grating to East Germans themselves, but perhaps more grating is the sense of disdain often felt in the western half of Germany; for East Germans, their country simply ceased to exist in 1990 as it was gobbled up by its larger, richer, more glamorous neighbour, and has been regarded as a failure ever since. For that reason, [Katja] Hoyer’s book [Beyond the Wall] is both enjoyable holiday reading and an important historical record for an ageing cohort of people who lived under the old system. To have one’s story told, in a sense, is to avoid annihilation.

Despite the similarities between the two totalitarian systems, East Germany almost defined itself as the anti-fascist state, and its origins lie in a group of communist exiles who fled from Hitler to seek safety in the Soviet Union. Inevitably, their story was almost comically bleak; 17 senior German Marxists in Russia ended up being executed by Stalin, suspected by the paranoid dictator of secretly working for Germany. Even some Jewish communists were accused of spying for the Nazis — which seems to a rational observer unlikely. As Hoyer writes, “More members of the KPD’s executive committee died at Stalin’s hands than at Hitler’s”.

Only two of the nine-strong German politburo survived life in Russia, one of these being Walter Ulbricht, the goatee-bearded veteran of the failed 1919 German revolution and communist party chairman in Berlin in the years before the Nazis came to power.

The war had brutalised the eastern part of Germany far more than the West. It suffered the revenge of the Red Army, including the then largest mass rape in history, and the forced expulsion of millions of Germans from further east (including Hoyer’s grandfather, who had walked from East Prussia). The country was utterly shattered.

From the start the Soviet section had huge disadvantages, not just in terms of raw materials or industry – western Germany has historically always been richer — but in having a patron in Russia. While the Americans boosted their allies through the Marshall Plan, the Soviets continued to plunder Germany; when they learned of uranium in Thuringia they simply turned up and took it, using locals as forced labour.

“In total, 60 per cent of ongoing East German production was taken out of the young state’s efforts to get on its feet between 1945 and 1953,” Hoyer writes: “Yet its people battled on. As early as 1950, the production levels of 1938 had been reached again despite the fact that the GDR had paid three times as much in reparations as its Western counterpart.”

After the war, so-called “Antifa Committees” formed across the Soviet zone, “made up of a wild mix of individuals, among them socialists, communists, liberals, Christians and other opponents of Nazism”. Inevitably, a broad and eclectic left front was taken over by communists who soon crushed all opposition.

And as with many regimes, state oppression grew worse over time. “By May 1953, 66,000 people languished in East German prisons, twice as many as the year before, and a huge figure compared to West Germany’s 40,000. The General Secretary’s revival of the ‘class struggle’, officially announced in the summer of 1952 as part of the state’s ‘building socialism’ programme, had escalated into a struggle against the population, including the working classes.” The party was also becoming dominated by an educated elite, as happened in pretty much all revolutionary regimes.

Protests began at the Stalinallee in Berlin on 16 June 1953, where builders marched towards the House of Ministries and “stood there in their work boots, the dirt and sweat of their labour still on their faces; many held their tools in their hands or slung over their shoulders. There could not have been a more fitting snapshot of what had become of Ulbricht’s dictatorship of the proletariat. The angry crowd chanted, ‘Das hat alles keinen Zweck, der Spitzbart muss weg!’ – ‘No point in reform until Goatee is gone!'”

The 1953 protests were crushed, the workers smeared as fascists, but three years later came Khrushchev’s famous denunciation of Stalin, which caused huge trauma to communists everywhere. “The shaken German delegation went back to their rooms to ponder the implications of what they had just learned.” By breakfast time, “Ulbricht had pulled himself together”, and decreed the new party line. Stalin, it was announced “cannot be counted as a classic of Marxism”.

Fortress Britain with Alice Roberts S01E03

Fortress Britain with Alice Roberts

Published 16 Apr 2023

August 11, 2023

Toward a more perfect Homo Sovieticus

Ed West on the interplay between Soviet ideology and Soviet humour during the Cold War:

Krushchev, Brezhnev and other Soviet leaders review the Revolution parade in Red Square, 1962.

LIFE magazine photo by Stan Wayman.

Revolutions go through stages, becoming more violent and extreme, but also less anarchic and more authoritarian. Eventually the revolutionaries mellow, and grow dull. Once in power they become more conservative, almost by definition, and more wedded to a set of sacred beliefs, with the jails soon filling up with people daring to question them.

The Soviet system was based on the idea that humans could be perfected, and because of this they even rejected Mendelian genetics and promoted the scientific fraud Trofim Lysenko; he had hundreds of scientists sent to the Gulag for refusing to conform to scientific orthodoxy. Lysensko once wrote that: “In order to obtain a certain result, you must want to obtain precisely that result; if you want to obtain a certain result, you will obtain it … I need only such people as will obtain the results I need.”

Thanks in part to this scientific socialism, harvests repeatedly failed or disappointed, and in the 1950s they were still smaller than before the war, with livestock counts lower than in 1926.

“What will the harvest of 1964 be like?” the joke went: “Average – worse than 1963 but better than 1965”.

The Russians responded to their brutal and absurd system with a flourishing culture of humour, as Ben Lewis wrote in Hammer and Tickle, but after the death of Stalin the regime grew less oppressive. From 1961, the KGB were instructed not to arrest people for anti-communist activity but instead to have “conversations” with them, so their “wrong evaluations of Soviet society” could be corrected.

Instead, the communists encouraged “positive satire” – jokes that celebrated the Revolution, or that made fun of rustic stupidity. “An old peasant woman is visiting Moscow Zoo, when she sets eyes on a camel for the first time. ‘Oh my God,’ she says, ‘look what the Bolsheviks have done to that horse’.” The approved jokes blamed bad manufacturing on lazy workers, while the underground and popular ones blamed the economic system itself. This official satire was of course nothing of the sort, making fun of the old order and the foolish hicks who still didn’t embrace the Revolution and the future.

Communists likewise set up anti-western “satirical” magazines in Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, where the same form of pseudo-satire could mock the once powerful and say nothing about those now in control.

Indeed in 1956, the East German Central Committee declared that the construction of socialism could “never be a subject for comedy or ridicule” but “the most urgent task of satire in our time is to give Capitalism a defeat without precedent”. That meant exposing “backward thinking … holding on to old ideologies”.

[…]

Leonid Brezhnev had a stroke in 1974 and another in 1976, becoming an empty shell and inspiring the gag: “The government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics has announced with great regret that, following a long illness and without regaining consciousness, the General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party and the President of the highest Soviet, Comrade Leonid Brezhnev, has resumed his government duties.”

Brezhnev was an absurd figure, presiding over a system few still believed in. His jacket was filled with medals – he had 260 awards by the time of his death – and when told that people were joking he was having chest expansion surgery to make room for all the medals he’d awarded himself, he apparently replied: “If they are telling jokes about me, it means they love me.”

August 10, 2023

MOBAT, WOMBAT, CONBAT | Anti-Tank Chats

The Tank Museum

Published 5 May 2023Welcome to this episode of Anti-Tank Chats. Today, Chris will be discussing the variations of a lesser-known weapon, the British Army’s B.A.T. (Battalion Anti-Tank Gun).

(more…)

August 5, 2023

Tempting Armageddon: Soviet vs. NATO Nuclear Strategy

Real Time History

Published 4 Aug 2023Since the inception of the nuclear bomb, military strategists have tried to figure out how to use them best. During the Cold War, this led to two very different doctrines but on both sides of the Iron Curtain the military wasn’t sure if you could actually win Nuclear War.

(more…)

August 1, 2023

QotD: US Army culture before the Korean War

The Doolittle Board of 1945-1946 met, listened to less than half a hundred complaints, and made its recommendations. The so-called “caste system” of the Army was modified. Captains, by fiat, suddenly ceased to be gods, and sergeants, the hard-bitten backbone of any army, were told to try to be just some of the boys. Junior officers had a great deal of their power to discipline taken away from them. They could no longer inflict any real punishment, short of formal court-martial, nor could they easily reduce ineffective N.C.O.’s. Understandably, their own powers shaky, they cut the ground completely away from their N.C.O.’s.

A sergeant, by shouting at some sensitive yardbird, could get his captain into a lot of trouble. For the real effect of the Doolittle recommendations was psychological. Officers had not been made wholly powerless — but they felt that they had been slapped in the teeth. The officer corps, by 1946 again wholly professional, did not know how to live with the newer code.

One important thing was forgotten by the citizenry: by 1946 all the intellectual and sensitive types had said goodbye to the Army — they hoped for good. The new men coming in now were the kind of men who join armies the world over, blank-faced, unmolded — and they needed shaping. They got it; but it wasn’t the kind of shaping they needed.

Now an N.C.O. greeted new arrivals with a smile. Where once he would have told them they made him sick to his stomach, didn’t look tough enough to make a go of his outfit, he now led them meekly to his company commander. And this clean-cut young man, who once would have sat remote at the right hand of God in his orderly room, issuing orders that crackled like thunder, now smiled too. “Welcome aboard, gentlemen. I am your company commander; I’m here to help you. I’ll try to make your stay both pleasant and profitable.”

This was all very democratic and pleasant — but it is the nature of young men to get away with anything they can, and soon these young men found they could get away with plenty.

A soldier could tell a sergeant to blow it. In the old Army he might have been bashed, and found immediately what the rules were going to be. In the Canadian Army — which oddly enough no American liberals have found fascistic or bestial — he would have been marched in front of his company commander, had his pay reduced, perhaps even been confined for thirty days, with no damaging mark on his record. He would have learned, instantly, that orders are to be obeyed.

But in the new American Army, the sergeant reported such a case to his C.O. But the C.O. couldn’t do anything drastic or educational to the man; for any real action, he had to pass the case up higher. And nobody wanted to court-martial the man, to put a permanent damaging mark on his record. The most likely outcome was for the man to be chided for being rude, and requested to do better in the future.

Some privates, behind their smirks, liked it fine.

Pretty soon, the sergeants, realizing the score, started to fraternize with the men. Perhaps, through popularity, they could get something done. The junior officers, with no sergeants to knock heads, decided that the better part of valor was never to give an unpopular order.

The new legions carried the old names, displayed the old, proud colors, with their gallant battle streamers. The regimental mottoes still said things like “Can Do”. In their neat, fitted uniforms and new shiny boots — there was money for these — the troops looked good. Their appearance made the generals smile.

What they lacked couldn’t be seen, not until the guns sounded.

T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness, 1963.

July 16, 2023

Cheap, Effective, Everywhere: The RPG-7

The Tank Museum

Published 7 Apr 2023Join Chris Copson as he presents our latest in Anti-Tank Chats. In this episode, we will delve into the fascinating history and practical applications of the RPG-7, a powerful anti-tank weapon.

(more…)

July 8, 2023

Canada’s Nuclear-Armed Cold War Interceptor: the story of the McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo

Polyus

Published 14 Aug 2020When Soviet or unidentified aircraft approached Canadian airspace in the 1960s and 70s, they were met by an iconic cold war interceptor. Armed with both conventional and nuclear weapons, they were a formidable foe in their day. It served to support NORAD and protect the Northern approaches into the North American heartland during the height of the Cold War. Although it was neither designed nor built in Canada, the reliable Voodoo remains a Canadian Cold War icon and was well loved by its ground crews and pilots.

0:00 Introduction

0:29 McDonnell F-101A development

1:06 F-101B Interceptor

3:11 Canada becomes involved with the Voodoo

4:15 The Nuclear question

5:08 Comparison with contemporaries

5:36 Operational History

8:04 Legacy and Retirement

8:48 Conclusion

(more…)

July 6, 2023

QotD: Liberalizing the US Army after WW2

In 1861, and 1917, the Army acted upon the civilian, changing him. But in 1945 something new happened. Suddenly, without precedent, perhaps because of changes in the emerging managerial society, professional soldiers of high rank had become genuinely popular with the Public. In 1861, and in 1917, the public gave the generals small credit, talked instead of the gallant militia. Suddenly, at the end of World War II, society embraced the generals.

And here it ruined them.

They had lived their lives in semibitter alienation from their own culture (What’s the matter, Colonel; can’t you make it on the outside?) but now they were sought after, offered jobs in business, government, on college campuses.

Humanly, the generals liked the acclaim. Humanly, they wanted it to continue. And when, as usual after all our wars, there came a great civilian clamor to change all the things in the army the civilians hadn’t liked, humanly, the generals could not find it in their hearts to tell the public to go to hell.

It was perfectly understandable that large numbers of men who served didn’t like the service. There was no reason why they should. They served only because there had been a dirty job that had to be done. Admittedly, the service was not perfect; no human institution having power over men can ever be. But many of the abuses the civilians complained about had come not from true professionals but from men with quickie diplomas, whose brass was much more apt to go to their heads than to those of men who had waited twenty years for leaves and eagles.

In 1945, somehow confusing the plumbers with the men who pulled the chain, the public demanded that the Army be changed to conform with decent, liberal society.

The generals could have told them to go to hell and made it stick. A few heads would have rolled, a few stars would have been lost. But without acquiescence Congress could no more emasculate the Army than it could alter the nature of the State Department. It could have abolished it, or weakened it even more than it did — but it could not have changed its nature. But the generals could not have retained their new popularity by antagonizing the public, and suddenly popularity was very important to them. Men such as Doolittle, Eisenhower, and Marshall rationalized. America, with postwar duties around the world, would need a bigger peacetime Army than ever before. Therefore, it needed to be popular with the people. And it should be made pleasant, so that more men would enlist. And since Congress wouldn’t do much about upping pay, every man should have a chance to become a sergeant, instead of one in twenty. But, democratically, sergeants would not draw much more pay than privates.

And since some officers and noncoms had abused their powers, rather than make sure officers and noncoms were better than ever, it would be simpler and more expedient — and popular — to reduce those powers. Since Americans were by nature egalitarian, the Army had better go that route too. Other professional people, such as doctors and clergymen, had special privileges — but officers, after all, had no place in the liberal society, and had better be cut down to size.

T.R. Fehrenbach, This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness, 1963.

June 24, 2023

Official mythmaking about the Empire Windrush in 1948

The Armchair General unpacks some of the story-spinning being conducted by the British government and various charities to mark the 75th anniversary of the voyage of the Empire Windrush from Jamaica to Britain:

“The National Windrush Monument” by amandabhslater is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 .

The Armchair General notes that there is much excitement about the 75th anniversary of the arrival of the ship called the Empire Windrush — which arrived on 22 June 1948 — and the contribution of the so-called Windrush Generation.

The myth currently being constructed is that those coming from Jamaica on the ship were invited, in order to rebuild a Britain struggling to recover from Word War II; we are told that, with so many young men killed in the fighting, Britain needed menial workers to selflessly come and rebuild our economy. Indeed, this view of events has been cemented in a much-lauded poem by Professor Laura Serrant.

Remember … you called.

Remember … you called

YOU. Called.

Remember, it was us, who came.Like almost any story constructed by governments and charities over at least the last thirty years, this narrative is dodgy at best and downright dishonest at worst. The simple fact is that the ship’s operator had expected to leave Jamaica under capacity and so offered passage at half price: many local men (and it was all men) took the opportunity.

Writing in The Spectator, in an article well worth reading in full, Ed West points out that the British government certainly did not encourage these immigrants at all.

Far from calling them, the British government was alarmed by the news. A Privy Council memo sent to the Colonial Office on 15 June stated that the government should not help the migrants: “Otherwise there might be a real danger that successful efforts to secure adequate conditions of these men on arrival might actually encourage a further influx.”

Colonial Secretary Arthur Creech Jones replied: “These people have British passports and they must be allowed to land.” But, he added confidently: “They won’t last one winter in England.” Indeed, Britain had recently endured some very harsh winters.

The Ministry of Labour was also unhappy about the arrival of the Jamaican men, minister George Isaacs warning that if they attempted to find work in areas of serious unemployment “there will be trouble eventually”. He said: “The arrival of these substantial numbers of men under no organised arrangement is bound to result in considerable difficulty and disappointment. I hope no encouragement will be given to others to follow their example.”

Nor was it the solely the evil Tories who were concerned:

Soon afterwards, 11 concerned Labour MPs wrote to Prime Minister Clement Attlee stating that the government should “by legislation if necessary, control immigration in the political, social, economic and fiscal interests of our people … In our opinion such legislation or administration action would be almost universally approved by our people.” The letter was sent on 22 June; that same day the Windrush arrived at Tilbury.

One can hardly be surprised: after all, 75 years ago, the Labour Party at least strove to represent the working class of Britain and the simple fact is that there was, at the time, massive unemployment — so much so that the government was heavily subsidising tickets to Australia (at £10) in order to encourage British people to emigrate (over 2 million British people left between 1948 and 1960).

There is a certain amount of well-intentioned inclusive myth-making in this story, and from a historical point of view the idea that “diversity built Britain”, the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, is bizarre. Until 1952 Britain was the richest country in Europe, after which we massively fell behind our continental rivals – so if diversity did “build” the country, it didn’t do a great job.

One can argue, I think, that the Windrush Generation made a great many contributions, in common with many immigrants; and if their contribution was not, in reality, as large as is claimed, then they share that with the EEC/EU’s Common Market which, again (and despite all the claims), brought no discernible benefit to the UK.

H/T to Tim Worstall for the link.

The Most Reliable and Versatile Sub-orbital Rockets Ever Made; the Black Brant Sounding Rockets

Polyus

Published 31 Aug 2018The Black Brant series of sounding rockets was a great success and a proud contribution to the global race for space. While not as glamorous as an orbital rocket, the Black Brants helped scientists from around the globe research and better understand the Aurora and the Earth’s ionosphere.

(more…)