Real Time History

Published 12 May 2023The question about the first modern war has caused lively debates among historians and YouTube comment sections alike. In this video we take a look at a few candidates and some arguments why they are or aren’t modern wars.

(more…)

May 13, 2023

What was the First Modern War?

May 9, 2023

How to destroy an industry with one simple trick

Ted Gioia on the precipitous rise and calamitous decline of the clickbait journalism model:

I was going to call this story the “tragedy of American journalism”. But when you dig into the details, it’s more a farce.

Let’s start with act one of this comedy. I could almost begin anywhere, but I picked an especially ridiculous case study — just wait until you learn the reason why.

Did that catch your attention?

It was supposed to. And I learned that from a now (mostly) forgotten website called Upworthy.

Almost exactly 10 years ago, Upworthy was “the fastest growing media site of all time”, according to Fast Company. They had turned news into a science. Upworthy was the future of journalism.

“Upworthy is known for its use of data to drive growth, testing up to 16 different headlines for a single story,” enthused that bright-eyed reporter for Fast Company. The end result was headlines so irresistible, millions of people clicked on them.

Here are some examples:

- A Gorgeous Waitress Gets Harassed By Some Jerk. Watch What Happens Next.

- A Teacher Ran to a Classroom to Break Up a Fight, but What She Found Was the Complete Opposite.

- It’s Twice The Size Of Alaska And Might Hold The Cure For Cancer. So Why Are We Destroying It?

- If You Could Press A Button And Murder Every Mosquito, Would You? Because That’s Kinda Possible.

You get the idea. The headline is in two parts — and it’s just a come-on. You have no idea what the article is about until you click on the link.

That was the whole point. But just wait until you learn the problem with this.

Facebook and other social media sites eventually discovered that people clicked on these links, but didn’t spent much time with the Upworthy articles — and rarely gave them likes and shares.

The stories just weren’t very good — and certainly not as interesting as the headlines. So the algorithms started to punish clickbait articles of this sort.

The Upworthy empire collapsed as quickly as it had risen.

In retrospect, the problem with this gimmicky strategy is obvious. If you trick people into clicking on garbage, your metrics are impressive for a few months. But eventually people can smell the garbage without even clicking on it.

There’s also a deeper reason for this collapse — which I’ll get to in a moment. And it helps us understand the current problems with journalism. But first we need to look at a couple more case studies.

May 6, 2023

The federal Liberals want even more control over the internet

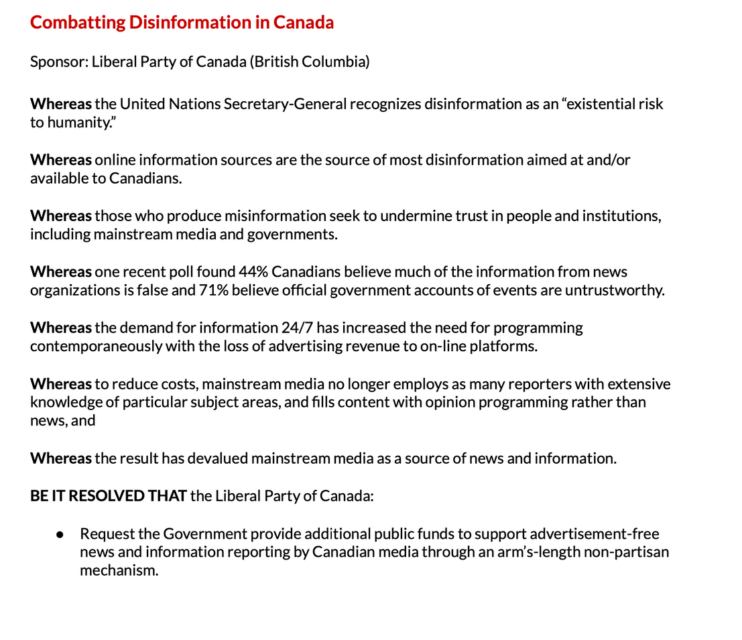

Paul Wells notes that a policy proposal at the Liberal conference this week indicates just how much the Liberal Party of Canada wants to control free expression on the internet:

Here on the 2023 Liberal convention’s “Open Policy Process” page are links to “Top 20 Resolutions” and “Fast-Tracked Resolutions”. The latter go straight to the plenary floor, the former go through a smaller preliminary debate and, if they pass, then on to the plenary. These things move fast because, in most cases, Liberals are paying only listless attention to the discussions. Policy is for New Democrats. Well, I mean, it used to be.

But sometimes words have meaning, so this morning I’m passing on one of the Top 20 Resolutions, from pages 12 and 13 of that book. This one comes to us from the British Columbia wing of the party.

It’s in two screenshots simply because it spreads across two pages. This is the entire resolution.

BC Liberals want “on-line information services” held “accountable for the veracity of material published on their platforms” by “the Government”. The Government would, in turn, “limit publication only to material whose sources can be traced”.

This resolution has no meaning unless it means I would be required to clear my posts through the federal government, before publication, so the “traceability” of my sources could be verified. I don’t suppose this clearance process would take too much more time than getting a passport or a response to an access-to-information request. Probably only a few months, at first. Per article.

After publication, “the Government” would hold me accountable for the veracity of my material, presumably through some new mechanism beyond existing libel law.

I’m not sure what “the Government” — I’m tickled by the way it’s capitalized, like Big Brother — would have made of this post, in which I quote an unnamed senior government official who was parked in front of reporters by “the Government” on the condition that he or she or they not be named. But by the plain meaning of this resolution, I would not have to wonder for long because that post would have been passed or cleared by the Government’s censors before publication, and I’m out of recourse if that process simply took longer than I might like.

May 5, 2023

May 4, 2023

QotD: Gesamtkunstwerk

… it occurs to me that movies aren’t the best example of the Current Year’s creative bankruptcy — music is. Somewhere below, I joked that Pink Floyd’s album The Wall was a modern attempt at a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk, a “total art work”. Wagner thought opera should be a complete aesthetic experience, that a great opera would have not just great music, but a great story in the libretto, great poetry in the lyrics, great painting in the set design, and so on, all of which would combine to something much greater than the sum of its already-excellent parts.

As I said, that’s awfully heavy for an album whose most famous song asks how can you have any pudding if you don’t eat your meat, but it’s nonetheless an accurate description of what Roger Waters was trying to do with the integrated concept album / movie / stage show. Whether or not he knew he was attempting a Gesamtkunstwerk in the full Wagnerian sense is immaterial, as is the question of whether or not he succeeded. Nor does it matter if The Wall is any good, musically or cinematically or lyrically.* The point is, he gave it one hell of a go … and nobody else has, even though these days it’d be far, far easier.

Consider what a band like Rush in their prime would’ve done with modern technology. I’m not a musician, but I’ve been told by people who are that you can make studio-quality stuff with free apps like Garage Band. Seriously, it’s fucking free. So is YouTube, and even high-quality digital cameras cost next to nothing these days, and even laptops have enough processor power to crank out big league video effects, with off-the-shelf software. I’m guessing (again, I’m no musician, let alone a filmmaker), but I’d wager some pretty good money you could make an actual, no-shit Gesamtkunstwerk — music, movie, the whole schmear — for under $100,000, easy. You think 2112-era Rush wouldn’t have killed it on YouTube?

I take a backseat to no man in my disdain for prog rock, but I have a hard time believing Neal Peart and the Dream Theater guys were the apex of rock’n’roll pretension. I realize I’ve just given the surviving members of Styx an idea, and we should all be thankful Kilroy Was Here was recorded in 1983, not 2013, because that yawning vortex of suck would’ve destroyed all life in the solar system, but I’m sure you see my point.** Why has nobody else tried this? Just to stick with a long-running Rotten Chestnuts theme, “Taylor Swift”, the grrl-power cultural phenomenon, is just begging for the Gesamtkunstwerk treatment. Apparently she’s trying real hard to be the June Carter Cash of the New Millennium™ these days, and hell, even I’d watch it.***

The fact that it hasn’t been attempted, I assert, is the proof that it can’t be done. The culture isn’t there, despite the tools being dirt cheap and pretty much idiot proof. Which says a LOT about the Current Year, none of it good.

* The obvious comment is that Roger Waters is no Richard Wagner, but that’s fatuous — even if you don’t like Wagner (I don’t, particularly), you have to acknowledge he’s about the closest thing to a universal artistic genius the human race has produced. It’s meaningless to say that Roger Waters isn’t in Wagner’s league, because pretty much nobody is in Wagner’s league. And philistine though I undoubtedly am, I’d much rather listen to The Wall than pretty much any opera — I enjoy the symphonic bits, but opera singing has always sounded like a pack of cats yodeling to me. I’m with the Emperor from Amadeus: “Too many notes.”

** If you have no idea what I’m talking about, then please, I’m begging you, do NOT go listen to “Mr. Roboto.” Whatever you do, don’t click that link …

… you clicked it, didn’t you? And now you’ll be randomly yelling “domo arigato, Mister Roboto!!” for days. You’ll probably get punched more than once for that. Buddy, I tried to warn you.

*** Anthropological interest only. I know I’m in the distinct minority on this one, but she never turned my crank, even in her “fresh-scrubbed Christian country girl” stage. Too sharp featured, and too obviously mercenary, even back then.

Severian, “More Scattered Thoughts”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-10-13.

April 23, 2023

From the Encyclopedia Britannica to Wikipedia

In the latest SHuSH newsletter, Ken Whyte recounts the decline and fall of the greatest of the print encyclopedias:

I remembered all this while reading Simon Garfield’s wonderful new book, All the Knowledge in the World: The Extraordinary History of the Encyclopedia. It’s an entertaining history of efforts to capture all that we know between covers, starting two thousand years ago with Pliny the Elder.

The star of Garfield’s show, naturally, is Encyclopedia Britannica, which dominated the field through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. By the time of its fifteenth edition in 1989, the continuously revised Britannica was comprehensive, reliable, scholarly, and readable, with 43 million words and 25,000 illustrations on a half million topics published over 32,640 pages in thirty-two beautifully designed Morocco-leather-bound volumes. It was the greatest encyclopedia ever published and probably the greatest reference tool to that time. It was sold door-to-door in the US by a sales force of 5,000.

Just as the glorious fifteenth edition was going to press, Bill Gates tried to buy Encyclopedia Britannica. Not a set — the whole company. He didn’t want to go into the reference book business. He believed that the availability of a CD-ROM encyclopedia would encourage people to adopt Microsoft’s Windows operating system. The Britannica people told Gates to get stuffed. They were revolted by the thought of their masterpiece reduced to an inexpensive plastic bolt-on to a larger piece of software for gimmicky home computers.

Like the executives at Blockbuster, the executives at Britannica eventually recognized the threat of digital technology but couldn’t see their way to abandoning their old business model and their old production standards and the reliable profits that came with large sets of big books. CD-ROMs seemed to them like a child’s toy.

Even as more of life moved online and the company’s prospects for growth dwindled, the Britannica executives could still not get their heads around abandoning the past and favoring a digital marketplace. They figured that their time-honored strategy of guilting parents into buying a shelf of books in service of their kids’ education would survive the digital challenge, not recognizing that parents would soon be assuaging their guilt by buying personal computers for their kids.

By the time Britannica brought out an overly expensive and not-very-good CD-ROM version of its encyclopedia in 1994, Gates had launched Encarta based on the much inferior Funk & Wagnalls. It might not have been the equal of the printed Britannica, but with its ease of use and storage, its much lower price point, and its many photos and videos of the Apollo moon landing and spuming whales, Encarta made a splash. It was selling a million copies a year in its third year of production — a number that no previous encyclopedia had come close to matching.

As it turned out, Britannica‘s last profitable year was 1990 when it sold 117,000 bound sets for $650 million and a profit of $40 million. With the launch of Encarta, its annual sales were reduced to 50,000 sets and it was laying off masses of employees.

Encarta‘s own life was relatively short. It closed in 2009, at which point it was selling for a mere $22.95. The world now belonged to Wikipedia.

April 16, 2023

The short-term mindset in architecture

Our house was built in the first half of the 19th century, although we’re not sure exactly when. We know it was here in the early 1840s but it could be 20 years older than that … in the first half of the 1800s, you didn’t need to get a building permit in Upper Canada before you started, and there was minimal government record-keeping at the time. Our house isn’t anything special architecturally, but it was built extremely solidly. It was intended to stand the test of time. This is not at all true for most of what we build today:

“Princes Street, New Town, Edinburgh, Scotland” by Billy Wilson Photography is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 .

I have had some work done on my house recently. For context, it’s an Edwardian terrace with a rear extension built sometime in the 1980s. Oddly fascinating for me was the sheer difference in build quality between the original section of the property and the newer part at the back. The older part of the house is sturdy, solid and lauded by the workmen as a “proper building”. The newer section has been a huge source of ridicule and contempt: shoddy timber placement, wobbly floors, dangerous electrical wiring, crumbling cement and poor brickwork plague it.

The tradesmen’s comments had me thinking a lot about the general quality of our infrastructure, both national and local, and how we sometimes take for granted the fact that a huge portion of what we use every day is so old. Not only that, but a lot of it is almost universally considered very beautiful and important to our shared cultural heritage.

Take a stroll through any city in Great Britain, and you are more than likely to at some point come across the “old town”. Despite the Luftwaffe’s (and post war town planner’s) best efforts, a lot of pre-war buildings still inhabit the centres of our towns and cities. These prove to be fine examples of the world we used to live in. Even in the poorest of cities, my own town of Hull for example, there exists a great plethora of dramatic and beautiful buildings which were constructed, almost exclusively, by the late Georgians, Victorians and Edwardians. Take a trip to London, Edinburgh, central Durham and a number of other places, and you will see that even the lampposts are adorned gorgeously, with striking and intricate ironwork.

Why is this? Why did they bother to do such a good job? Why do we still heavily rely on their work for our own sense of cultural identity and our basic infrastructural needs? Why can’t our own contemporary efforts compete, despite great advances in the field of civil engineering and construction materials? I think the answer boils down to one thing: civic pride.

The Victorians were building for eternity; we build for temporary needs in a utilitarian fashion. They knew their “mission”, and they saw it an absolute necessity to make everything they did permanent; we do not. They designed buildings to be functional and beautiful; we seek to make buildings which will be functional for 50 years before they are “recycled”.

Speak to a modern student of architecture about their course, and you will find that very few opportunities exist for those who want to pursue a path for traditional design techniques. Their learning aim is to make things which can be used temporarily, then pulled down for something else. This is an attitude which would be totally alien to the Victorians who designed and built the lecture halls these students now learn in.

April 14, 2023

The trust deficit is getting worse every day

Ted Gioia provides more evidence that the scarcest thing in the world today is getting ever more scarce:

Here are some news stories from recent days. Can you tell me what they have in common?

- Scammers clone a teenage girl’s voice with AI — then use it to call her mother and demand a $1 million ransom.

- Millions of people see a photo of Pope Francis wearing a goofy white Balenciaga puffer jacket, and think it’s real. But after the image goes viral, news media report that it was created by a construction worker in Chicago with deepfake technology.

- Twitter changes requirements for verification checks. What was once a sign that you could trust somebody’s identity gets turned into a status symbol, sold to anybody willing to pay for it. Within hours, the platform is flooded with bogus checked accounts.

- Officials go on TV and tell people they can trust the banking system—but depositors don’t believe them. High profile bank failures from Silicon Valley to Switzerland have them spooked. Over the course of just a few days, depositors move $100 billion from their accounts.

- ChatGPT falsely accuses a professor of sexual harassment — and cites an article that doesn’t exist as its source. Adding to the fiasco, AI claims the abuse happened on a trip to Alaska, but the professor has never traveled to that state with students.

- The Department of Justice launches an investigation into China’s use of TikTok to spy on users. Another popular Chinese app allegedly can bypass users’ security to “monitor activities on other apps, check notifications, read private messages and change settings.”

- The FBI tells travelers to avoid public phone charging stations at airports, hotels and other locations. “Bad actors have figured out ways to use public USB ports to introduce malware and monitoring software onto devices,” they warn.

The missing ingredient in each of these stories is trust.

Everybody is trying to kill it — criminals, technocrats, politicians, you name it. Not long ago, Disney was the only company selling a Fantasyland, but now that’s the ambition of every tech empire.

The trust crisis could hardly be more intense.

But it’s hidden from view because there’s so much information out there. We are living in a culture of abundance, especially in the digital world. So it’s hard to believe than anything in the information economy is scarce.

Whatever you want, you can get — and usually for free. You can have free news, free music, free videos, free everything. But you get what you pay for, as the saying goes. And it was never truer than right now — when all this free stuff is starting to collapse in a fog of fakery and phoniness.

Tell me what source you trust, and I’ll tell you why you’re a fool. As B.B. King once said: “Nobody loves me but my mother — and she could be jivin’ too.”

Years ago, technology made things more trustworthy. You could believe something because it was validated by photos, videos, recordings, databases and other trusted sources of information.

Seeing was believing — but not anymore. Until very recently, if you doubted something, you could look it up in an encyclopedia or other book. But even these get changed retroactively nowadays.

For example, people who consult Wikipedia to understand the economy might be surprised to learn that the platform’s write-up on “recession” kept changing in recent months — as political operatives and spinmeisters fought over the very meaning of the word. It got so bad that the site was forced to block edits on the entry.

There’s an ominous recurring theme here: The very technologies we use to determine what’s trustworthy are the ones most under attack.

Trust used to be a given in most western countries … it was a key part of what made us all WEIRD. Mass immigration from non-WEIRD countries dented it, but conscious perversion of trust relationships by government, media, public health, and education authorities has caused far more — and longer lasting — damage to our culture. Trust used to be given freely, but now must be earned. And that’s difficult for organizations that have proven repeatedly that they can’t be trusted.

Twists and turns in the “Twitter Files” narrative

Matt Taibbi recounts how he got involved in the “Twitter Files” in the first place through the hysterical and hypocritical responses of so many mainstream media outlets up to the most recent twist as Twitter owner Elon Musk burns off so much of the credit he got for exposing the information in the first place:

I was amazed at this story’s coverage. From the Guardian last November: “Elon Musk’s Twitter is fast proving that free speech at all costs is a dangerous fantasy.” From the Washington Post: “Musk’s ‘free speech’ agenda dismantles safety work at Twitter, insiders say.” The Post story was about the “troubling” decision to re-instate the Babylon Bee, and numerous stories like it implied the world would end if this “‘free speech’ agenda” was imposed.

I didn’t have to know any of the particulars of the intramural Twitter dispute to think anyone who wanted to censor the Babylon Bee was crazy. To paraphrase Kurt Vonnegut, going to war against a satire site was like dressing up in a suit of armor to attack a hot fudge sundae. This was an obvious moral panic and the very real consternation at papers like the Washington Post and sites like Slate over these issues seemed to offer the new owners of Twitter a huge opening. With critics this obnoxious, even a step in the direction of free speech values would likely win back audiences that saw the platform as a humorless garrison of authoritarian attitudes.

This was the context under which I met Musk and the circle of adjutants who would become the go-betweens delivering the material that came to be known as the Twitter Files. I would have accepted such an invitation from Hannibal Lecter, but I actually liked Musk. His distaste for the blue-check thought police who’d spent more than a half-year working themselves into hysterics at the thought of him buying Twitter — which had become the private playground of entitled mainstream journalists — appeared rooted in more than just personal animus. He talked about wanting to restore transparency, but also seemed to think his purchase was funny, which I also did (spending $44 billion with a laugh as even a partial motive was hard not to admire).

Moreover the decision to release the company’s dirty laundry for the world to see was a potentially historic act. To this day I think he did something incredibly important by opening up these communications for the public.

Taibbi and the other Twitter File journalists were, of course, damned by the majority of the establishment media outlets and accused of every variant of mopery, dopery, and gross malfeasance by the blue check myrmidons. Some of that must have been anticipated, but a lot of it seems to have surprised even Taibbi and company for its blatant hypocrisy and incandescent rage.

But all was not well between the Twitter Files team and the new owner of Twitter:

We were never on the same side as Musk exactly, but there was a clear confluence of interests rooted in the fact that the same institutional villains who wanted to suppress the info in the Files also wanted to bankrupt Musk. That’s what makes the developments of the last week so disappointing. There was a natural opening to push back on the worst actors with significant public support if Musk could hold it together and at least look like he was delivering on the implied promise to return Twitter to its “free speech wing of the free speech party” roots. Instead, he stepped into another optics Punji Trap, censoring the same Twitter Files reports that initially made him a transparency folk hero.

Even more bizarre, the triggering incident revolved around Substack, a relatively small company that’s nonetheless one of the few oases of independent media and free speech left in America. In my wildest imagination I couldn’t have scripted these developments, especially my own very involuntary role.

I first found out there was a problem between Twitter and Substack early last Friday, in the morning hours just after imploding under Mehdi Hasan’s Andrey Vyshinsky Jr. act on MSNBC. As that joyous experience included scenes of me refusing on camera to perform on-demand ritual criticism of Elon Musk, I first thought I was being pranked by news of Substack URLs being suppressed by him. “No way,” I thought, but other Substack writers insisted it was true: their articles were indeed being labeled, and likes and retweets of Substack pages were being prohibited.

April 11, 2023

The amplifier may have been the key technological innovation that let vocalists and guitarists become stars

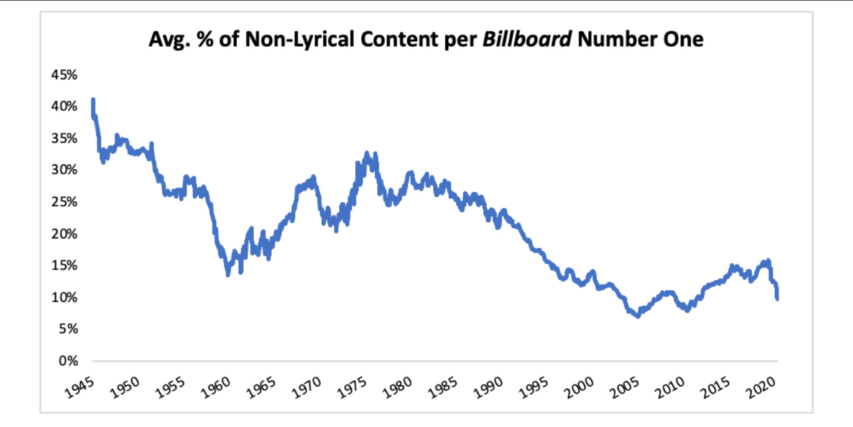

Chris Dalla Riva, guest-posting at Ted Gioia’s Honest Broker, considers how instrumental hits used to be far more popular before (among other factors) microphone technology let vocalists compete with orchestras and guitar amplifiers let the strings dominate the pop music market:

Clarinet players aren’t sex symbols. I say this with no disrespect for those that play the single-reeded woodwind. But if you asked a random person on the street to name a clarinet player, I suspect most people couldn’t come up with one, let alone one known for their good looks. Then again, this isn’t a particular indictment of clarinetists. If you asked that same person to name a sexy musician, I’d bet a large sum of money they’d name a vocalist.

This wasn’t always the case, though. In Kelly Schrum’s book Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls’ Culture, 1920-1945, she notes that in high school yearbooks in the 1930s some students expressed a passion for “Benny Goodman while other girls had a ‘weakness’ for Artie Shaw or were classified as Glenn Miller ‘fanatics’, faithful fans of Tommy Dorsey, or ‘Happy while listening to Kay Kyser’. Cab Calloway, Xavier Cugat, and Harry James were also popular favorites.” Of those musicians, only Calloway was a singer. Goodman, Shaw, and Kyser played the clarinet. Miller and Dorsey played the trombone. Cugat played violin. James played trumpet.

Given that our contemporary musical world is dominated by vocalists, this seems bizarre. It feels like if you have a musical group it must be centered around the vocalist. If we measure the average percent of instrumental content per Billboard number hit between 1940 and 2021, we see demonstrable evidence for not just the decline of the instrumental superstar but the instrumentalist generally, with the sharpest declines beginning in the 1950s and the 1990s.

NOTE: Data from July 1940 to August 1958 comes from Billboard‘s Best Sellers in Stores chart. After August 1958, Billboard deprecated that chart in favor of the Hot 100, which initially aggregated sales, jukebox, and radio data. The Hot 100 remains the premiere pop chart, though it has come to include many more sources, like streams and digital downloads. The above displays a 50-song rolling average.

What’s going on here? How could throngs of high schoolers long for the clarinet-wielding Artie Shaw 80 years ago when most teenagers today would struggle to name a musician who isn’t also a singer. I believe it comes down to four factors: improved technology, the 1942 musicians’ strike, WWII, television, and hip-hop.

Improved Technology

In the VH1-produced documentary The Brian Setzer Orchestra Story, Dave Kaplan, Setzer’s manager, recounts a conversation he had with Setzer before assembling a guitar-fronted big band in the 1990s: “Nobody had ever fronted a big band with an electric guitar … I asked Brian, ‘Why wouldn’t somebody have tried it?’ [Setzer replied,] ‘Well there weren’t amps.'” Albeit a simplification, Setzer’s quip is pretty accurate.

While there were some famous guitar players among the big bands of the first half of the 20th century, we don’t see the guitar become a driving force in popular music until amplification improved. This was not only a boon for the guitarists but also vocalists. Unlike brass and wind instruments, you can sing while you play the guitar. Thus, it’s not shocking that the rise of the guitar coincided with the rise of the vocalist.

But it wasn’t just guitar amplification technology that was vital. It was also microphone technology. Again, microphones had to improve so vocalists could compete with the cacophony of a loud band. On top of this, recording had to change to capture more subtlety in the human voice.

April 8, 2023

QotD: Rome’s “excess labour” problem

Back when historians actually cared about the behavior of real people, they looked at big-picture stuff like “labor mobility”. Ever wonder why all that cool shit Archimedes invented never went anywhere? The Romans had a primitive steam turbine. Why did it remain a clever party trick? Romans were fabulous engineers — these are the guys, you’ll recall, who just built a harbor in a convenient spot when they couldn’t find a good enough natural one. Surely their eminently practical brains could spot some use for these gizmos …?

The thing is — as old-school historians would tell you if any were still alive — technology is all about saving labor. Physical labor, mental labor, same deal. Consider the abacus, for instance. It’s a childishly simple device — it’s literally a child’s toy now — but think about actually doing math with it, when the only alternative is scratch paper. How much time do you save, not having to jot things down (remember where you put the jottings, etc.)?

I’m sure you see where this is going. The Romans did NOT lack for labor. They had, in fact, the exact opposite problem: Far, far too much labor. It’s almost a cliché to say that a particular group in the ancient world didn’t qualify as a “civilization” until they started putting up as ginormous a monument as they could figure out. They raised monuments for lots of reasons, of course, but not least among them was the excess-labor problem. What else are you supposed to do with the tribe you just conquered? Unless you want to wipe them out, to the last old man, woman, and child, slavery is the only humane solution.

If that’s true, then the opposite should also hold — technological innovation starts with a labor shortage. Survey says … yep. There’s a reason the Scientific Revolution dates to the Renaissance: The massive labor shortage following the Black Death. That this is also the start of the great age of exploration is also no accident. While the labor (over-)supply was fairly constant in the ancient world, once technological innovation really got going, the labor-supply pendulum started swinging wildly. The under-supply after the Black Death led to over-supply once technological work-arounds were discovered; that over-supply was exported to the colonies, which were grossly under-supplied, etc.

In short: If you want to know what kind of society you’re going to have, look at labor mobility.

Severian, “Excess Labor”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-07-28.

April 4, 2023

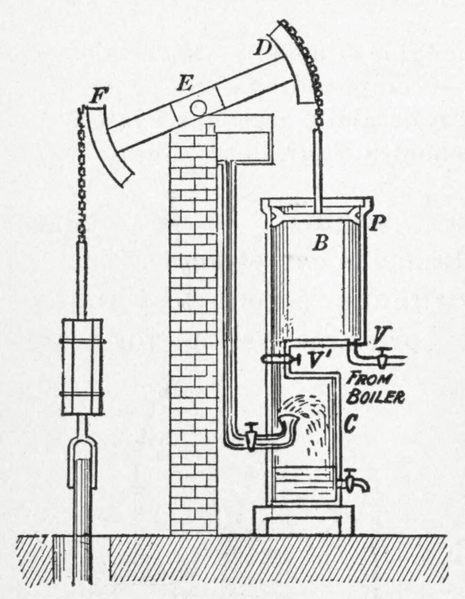

When the steam engine itself was an “intangible”

In the latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes explains why the steam engine patent of James Watt didn’t immediately lead to Watt and his partner Matthew Boulton building a factory to create physical engines:

Diagram of a Watt steam engine from Practical physics for secondary schools (1913).

Wikimedia Commons.

… one of the most famous business partnerships of the British Industrial Revolution — that between Matthew Boulton and James Watt from 1775 — was originally almost entirely based on intangibles.

That probably sounds surprising. James Watt — a Scottish scientific instrument-maker, chemist and civil engineer — became most famous for his improvements to the steam engine, an almost archetypal example of physical capital. In the late 1760s he radically improved the fuel efficiency of the older Newcomen engine, and then developed ways to regulate the motions of its piston — traditionally applied only to pumping water — so that it could be suitable for directly driving machinery (I’ll write more on the invention itself soon). His partnership with Matthew Boulton, a Birmingham manufacturer of buttons, candlesticks, metal buckles and the like — then called “toys” — was also based from a large, physical site full of specialised machinery: the Soho Manufactory. On the face of it, these machines and factories all sound very traditionally tangible.

But the Soho Manufactory was largely devoted to Boulton’s other, older, and ongoing businesses, and it was only much later — over twenty years after Boulton and Watt formally became partners — that they established the Soho Foundry to manufacture the improved engines themselves. The establishment of the Soho Foundry heralded James Watt’s effective retirement, with the management of this more tangible concern largely passing to his and Boulton’s sons. And when Watt retired formally, in 1800, this coincided with the full depreciation of the intangible asset upon which he and Boulton had built their business: his patent.

Watt had first patented his improvements to the steam engine in 1769, giving him a 14-year window in which to exploit them without any legal competition. But his financial backer, John Roebuck, who had a two-thirds share in the patent, was bankrupted by his other business interests and struggled to support the engine’s development. Watt thus spent the first few years of his patent monopoly as a consultant on various civil engineering projects — canals, docks, harbours, and town water supplies — in order to make ends meet. The situation gave him little time, capital, or opportunity to exploit his steam engine patent until Roebuck was eventually persuaded to sell his two-thirds share to Matthew Boulton. With just eight years left on the patent, and having already wasted six, Boulton and Watt lobbied Parliament to grant them an extension that would allow them to bring their improvements into full use. In 1775 Watt’s patent was extended by Parliament for a further twenty-five years, to last until 1800. It was upon this unusually extended patent that they then built their unusually and explicitly intangible business.

How was it intangible? As Boulton and Watt put it themselves, “we only sell the licence for erecting our engines, and the purchaser of such licence erects his engine at his own expence”. This was their standard response to potential customers asking how much they would charge for an engine with a piston cylinder of particular dimensions. The answer was, essentially, that they didn’t actually sell physical steam engines at all, so there was no way of estimating a comparable figure. Instead, they sold licences to the improvements on a case-by-case basis — “we make an agreement for each engine distinctly” — by first working out how much fuel a standard, old-style Newcomen engine would require when put to use in that place and context, and then charging only a third of the saving in fuel that Watt’s improvements would provide. “The sum therefore to be paid during the working of any engine is not to be determined by the diameter of the cylinder, but by the quantity of coals saved and by the price of coals at the place where the engine is erected.” They fitted the licensed engines with meters to see how many times they had been used, sending agents to read the meters and collect their royalties every month or year, depending on the location.

This method of charging worked well for refitting existing Newcomen engines with Watt’s improvements — in those cases the savings would be obvious. It also meant that Boulton and Watt incentivised themselves to expand the total market for steam engines. The older Newcomen engines were mainly used for pumping water out of coal mines, where the coal to run them was at its cheapest. It was one of the few places where Newcomen engines were cost-effective. But for Watt and Boulton it was at the places where coals were most expensive, and where their improvements could thus make the largest fuel savings, that they could charge the highest royalties. As Boulton wrote to Watt in 1776, the licensing of an engine for the coal mine of one Sir Archibald Hope “will not be worth your attention as his coals are so very cheap”. It was instead at the copper and tin mines of Cornwall, where coal was often expensive, having to be transported from Wales, that the royalties would be the most profitable. As Watt put it to an old mentor of his in 1778, “our affairs in other parts of England go on very well but no part can or will pay us so well as Cornwall”.

April 2, 2023

March 31, 2023

Bill C-11 should properly be called the “Justin Trudeau Internet Censorship Bill”

In The Free Press, Rupa Subramanya explains why the federal government’s Bill C-11 is a terrible idea:

Canada’s Liberals insist the point of Bill C-11 is simply to update the 1991 Broadcasting Act, which regulates broadcasting of telecommunications in the country. The goal of the bill, according to a Ministry of Canadian Heritage statement, is to bring “online broadcasters under similar rules and regulations as our traditional broadcasters”.

In other words, streaming services and social media, like traditional television and radio stations, would have to ensure that at least 35 percent of the content they publish is Canadian content — or, in Canadian government speak, “Cancon”.

The bill is inching toward a final vote in the Canadian Senate as soon as next month. It’s expected to pass. If it does, YouTube CEO Neal Mohan said in an October blog post, the same creators the government says it wants to help will, in fact, be hurt.

[…]

If you’re confused by all this — if you’re wondering why the Liberal Party and its allies in these quasi-governmental organizations are suddenly so worried about Canada’s national identity — that’s understandable.

In a 2015 interview with The New York Times, Trudeau proudly declared, “There is no core identity, no mainstream in Canada.” Canada, he explained, is “the first postnational state”. The authorized, two-volume biography of Trudeau’s father, former prime minister Pierre Trudeau, is called Citizen of the World. Pablo Rodriguez maintains dual citizenship — in Canada and in Argentina, where he was born.

So why is Trudeau, of all people, championing this legislation? There’s an easy explanation — and it has nothing to do with borders or culture.

“Bill C-11 is a government censorship bill masquerading as a Canadian culture bill,” Jay Goldberg, a director at the conservative Canadian Taxpayers Federation, told me. Referring to the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission, Goldberg said, “The government is intending to give the power to the CRTC to be able to filter what we see in our news feeds, what we see in our streaming feeds, what we see on social media.”

Supporters of Bill C-11 emphasize it would affect only YouTube, Netflix, Amazon, TikTok, and other Big Tech platforms; the Heritage Ministry statement notes “the bill does not apply to individual Canadians”. But the language is so vague that it’s unclear how it would actually be implemented.

For example, it would be up to CRTC regulators to decide what constitutes “Canadian” content. The singer The Weeknd was born in Toronto but now mostly lives in Los Angeles. Does he still count as Canadian? What about rock n’ roller Bryan Adams, who was born in Kingston, Ontario, and spends a great deal of time in Europe?

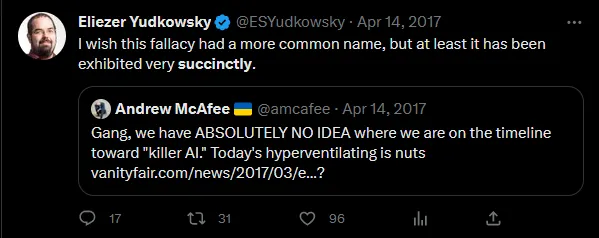

“We have absolutely no idea how AI will go, it’s radically uncertain”… “Therefore, it’ll be fine” (?)

Scott Alexander on the Safe Uncertainty Fallacy, which is particularly apt in artificial intelligence research these days:

The Safe Uncertainty Fallacy goes:

- The situation is completely uncertain. We can’t predict anything about it. We have literally no idea how it could go.

- Therefore, it’ll be fine.

You’re not missing anything. It’s not supposed to make sense; that’s why it’s a fallacy.

For years, people used the Safe Uncertainty Fallacy on AI timelines:

Since 2017, AI has moved faster than most people expected; GPT-4 sort of qualifies as an AGI, the kind of AI most people were saying was decades away. When you have ABSOLUTELY NO IDEA when something will happen, sometimes the answer turns out to be “soon”.

Now Tyler Cowen of Marginal Revolution tries his hand at this argument. We have absolutely no idea how AI will go, it’s radically uncertain:

No matter how positive or negative the overall calculus of cost and benefit, AI is very likely to overturn most of our apple carts, most of all for the so-called chattering classes.

The reality is that no one at the beginning of the printing press had any real idea of the changes it would bring. No one at the beginning of the fossil fuel era had much of an idea of the changes it would bring. No one is good at predicting the longer-term or even medium-term outcomes of these radical technological changes (we can do the short term, albeit imperfectly). No one. Not you, not Eliezer, not Sam Altman, and not your next door neighbor.

How well did people predict the final impacts of the printing press? How well did people predict the final impacts of fire? We even have an expression “playing with fire.” Yet it is, on net, a good thing we proceeded with the deployment of fire (“Fire? You can’t do that! Everything will burn! You can kill people with fire! All of them! What if someone yells “fire” in a crowded theater!?”).

Therefore, it’ll be fine:

I am a bit distressed each time I read an account of a person “arguing himself” or “arguing herself” into existential risk from AI being a major concern. No one can foresee those futures! Once you keep up the arguing, you also are talking yourself into an illusion of predictability. Since it is easier to destroy than create, once you start considering the future in a tabula rasa way, the longer you talk about it, the more pessimistic you will become. It will be harder and harder to see how everything hangs together, whereas the argument that destruction is imminent is easy by comparison. The case for destruction is so much more readily articulable — “boom!” Yet at some point your inner Hayekian (Popperian?) has to take over and pull you away from those concerns. (Especially when you hear a nine-part argument based upon eight new conceptual categories that were first discussed on LessWrong eleven years ago.) Existential risk from AI is indeed a distant possibility, just like every other future you might be trying to imagine. All the possibilities are distant, I cannot stress that enough. The mere fact that AGI risk can be put on a par with those other also distant possibilities simply should not impress you very much.

So we should take the plunge. If someone is obsessively arguing about the details of AI technology today, and the arguments on LessWrong from eleven years ago, they won’t see this. Don’t be suckered into taking their bait.

Look. It may well be fine. I said before my chance of existential risk from AI is 33%; that means I think there’s a 66% chance it won’t happen. In most futures, we get through okay, and Tyler gently ribs me for being silly.

Don’t let him. Even if AI is the best thing that ever happens and never does anything wrong and from this point forward never even shows racial bias or hallucinates another citation ever again, I will stick to my position that the Safe Uncertainty Fallacy is a bad argument.