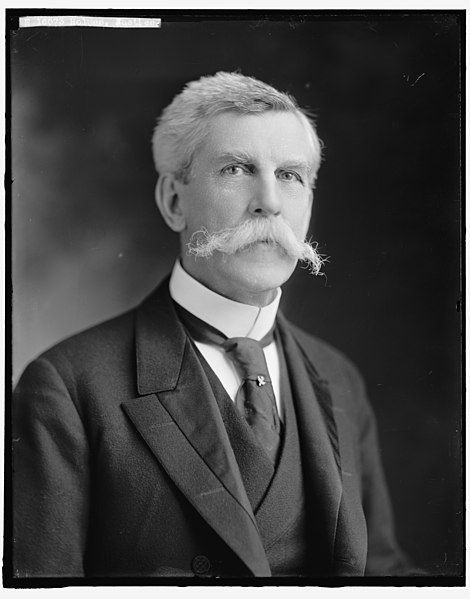

Scott was a slave who claimed to be free because his owners had taken him to U.S. states where slavery was outlawed; in ruling on the case, Chief Justice Roger Taney, writing for a 7-2 majority, found that Blacks were “beings of an inferior order” who, under the constitution, “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

The Scott decision is now considered an important contributing cause of the U.S. Civil War, which began four years later. It proved, beyond anyone’s doubt, President Abraham Lincoln’s maxim that a sovereign nation could not survive half-slave and half-free. Northern states might be capable of abolishing slavery locally, but this “abolition” would never apply to imported slaves from elsewhere considered as property. One cannot fully understand U.S. history, never mind the progress of its law, without studying and appreciating Taney’s cruel language.

And, indeed, for the world at large, Dred Scott is an unsurpassed reminder of the distinction between law and justice, and of the limitations of a highly reverenced written constitution. Taney not only accepted the (irrefutable) argument that the constitution explicitly countenanced slavery: he wrote fawningly of the Founding Fathers as great men, “high in their sense of honour,” who could never have upheld absolute equality before the law on one hand while hypocritically denying it to Blacks in practice. The Declaration of Independence’s claim that “all men are created equal,” the ex-slaveowner Taney wrote, was never understood by anyone to include inferior races.

Abolitionists of the time saw the innate hypocrisy: the contemporary newspaper editor William Lloyd Garrison risked his life by calling the constitution “a league with hell.” But [University of Buffalo law professor Matthew] Steilen thinks it is better not to expose Black students to the details of that debate. Reading Taney’s “gratuitously insulting and demeaning” words and arguments, he tweeted, is likely to, and there is no other way to put this, injure their feelings. To inquire too deeply into the detail of slavery, and of the law that shielded it, would require Black students to “relive the humiliation” of Dred Scott.

Colby Cosh, “Another Day in a Feelings-First World”, NP Platformed, 2021-06-09.

September 12, 2021

QotD: The US Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857

June 3, 2021

John McWhorter on Affirmative Action

In the latest post at It Bears Mentioning, John McWhorter outlines the history of Affirmative Action in American schooling and explains why it’s no longer doing anything useful and should be re-oriented to actually help disadvantaged students of all races:

I do not oppose Affirmative Action. I simply think it should be based on disadvantage, not melanin. It made sense – logical as well as moral – to adjust standards in the wake of the implacable oppression of black people until the mid-1960s.

When Affirmative Action began in the 1960s, largely with black people in mind, the overlap between blackness and disadvantage was so large that the racialized intent of the policy made sense. Most black people lived at or below the poverty line. Being black and middle class was, as one used to term it, “fortunate”. Plus, black people suffered open discrimination regardless of socioeconomic status, in ways for more concrete than microaggressions and things only identifiable via Implicit Association Testing and the like. In a sense, black people were all in the same boat.

Luckily, Affirmative Action worked. By the 1980s, it was no longer unusual or “fortunate” to be black and middle class. I would argue that by that time, it was time to reevaluate the idea that anyone black should be admitted to schools with lowered standards. I think Affirmative Action today should be robustly practiced — but on the basis of socioeconomics.

A common objection is that this would help too many poor whites (as if that’s a bad thing?). But actually, brilliant and non-partisan persons have argued that basing preferences on socioeconomics would actually bring numbers of black people into the net that almost anyone would be satisfied with.

I’m no odd duck on my sense that Affirmative Action being about race had passed its sell-by date after about a generation. At this very time, it had become clear, to anyone really looking, that the black people benefitting from Affirmative Action were no longer mostly poor – as well as that simply plopping truly poor black people into college who had gone to awful schools had tended not to work out anyway. It was no accident that in 1978 came the Bakke decision, where Justice Lewis Powell inaugurated the new idea that Affirmative Action would serve to foster “diversity”, the idea being that diversity in the classroom made for better learning.

I highly suspect that most people have always had to make a slight mental adjustment to get comfortable with this idea, as standard as it now is in enlightened discussion. Do students in classes with a certain mixture of races learn better? Really? Not that there might not be benefits to students of different races being together for other reasons. But does diversity make for better learning? Has that been proven?

As you might expect, it has not – and in fact the idea has been disproven, again and again. No one will tell you this when the next round of opining on racial preferences comes about. But this doesn’t mean it isn’t true.

April 21, 2021

QotD: Freedom of speech in Canada

We have nothing like the First Amendment; our Supreme Court is a Leftist institution par excellence and has even decreed in effect that truth is no defense in cases where “protected groups” are insulted or offended. Paragraph 140 of a 2013 Judgment finds “that not all truthful statements must be free from restriction. Truthful statements can be interlaced with harmful ones or otherwise presented in a manner that would meet the definition of hate speech.” Section 15 (2) of the Constitution Act of 1982 abridges the rights that section 15(1) guarantees Canadian citizens.

Further, our Human Rights Tribunals are Soviet-style shadow courts that discard due process in adjudicating cases of supposed discrimination or “hate speech.” As Canadian Human Rights Commissioner Dean Steacy said: “Freedom of speech is an American concept, so I don’t give it any value.” Openness to everything except freedom of speech, chartered principle and practical reason is the hallmark of our justice system, as it is of the nation. As Carl Sagan quipped in The Demon-Haunted World: “It pays to keep an open mind, but not so open your brains fall out.”

David Solway, “The Canadian Mind: A Culture So Open, Its ‘Brains Fall Out'”, PJ Media, 2018-10-10.

January 30, 2021

Obey your technocratic elites, peasant!

Scott Alexander considers some historical (and current) examples of you peasants being steamrolled by the powers of the government at the behest of the technological elites of the day:

I am not defending technocracy.

Nobody ever defends technocracy. It’s like “elitism” or “statism”. There is no Statist Party. Nobody holds rallies demanding more statism. There is no Citizens for Statism Facebook page with thousands of likes and followers.

[…] it worries me that everyone analyzes the exact same three examples of the failures of top-down planning: Soviet collective farms, Brasilia, and Robert Moses. I’d like to propose some other case studies:

1. Mandatory vaccinations: Technocrats used complicated mathematical models to determine that mass vaccination would create a “herd immunity” to disease. Certain that their models were “objectively” correct and so could not possibly be flawed, these elites decided to force vaccines on a hostile population. Despite popular protest (did you know that in 1800s England, anti-smallpox-vaccine rallies attracted tens of thousands of demonstrators?), these technocrats continued to want to “arrogantly remake the world in their image,” and pushed ahead with their plan, ignoring normal citizens’ warnings that their policies might have unintended consequences, like causing autism.

2. School desegregation: Nine unelected experts with Harvard and Yale degrees, using a bunch of Latin terms like a certiori and de facto that ordinary people could not understand let alone criticize, decided to completely upend the traditional education system of thousands of small communities to make it better conform to some rules written in a two-hundred-year-old document. The communities themselves opposed it strongly enough to offer violent resistance, but the technocrats steamrolled over all objections and sent in the National Guard to enforce their orders.

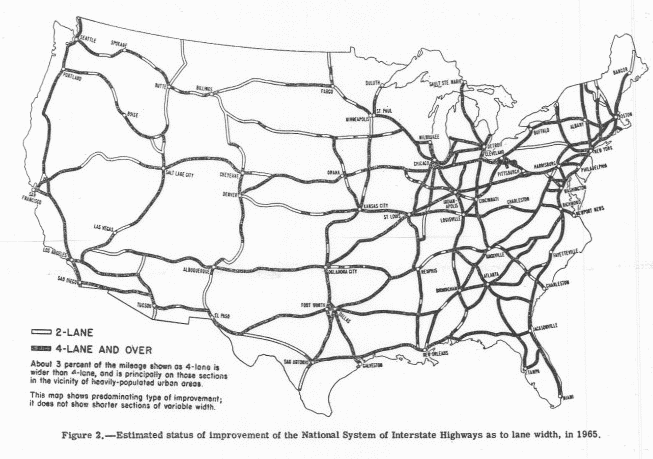

US Highway System needs in 1965 from “Needs of the Highway Systems 1955-1984”, a letter from the Secretary of Commerce to the House Committee on Public Works, approved May 6, 1954.

US Government Printing Office via Wikimedia Commons.3. The interstate highway system: 1950s army bureaucrats with a Prussia fetish decided America needed its own equivalent of the Reichsautobahn. The federal government came up with a Robert-Moses-like plan to spend $114 billion over several decades to build a rectangular grid of numbered giant roads all up and down the country, literally paving over whatever was there before, all according to pre-agreed federal standards. The public had so little say in the process that they started hundreds of freeway revolts trying to organize to prevent freeways from being built through their cities; the government crushed these when it could, and relocated the freeways to less politically influential areas when it couldn’t.

4. Climate change: In the second half of the 20th century, scientists determined that carbon dioxide emissions were raising global temperatures, with potentially catastrophic consequences. Climatologists created complicated formal models to determine how quickly global temperatures might rise, and economists designed clever from-first-principle mechanisms that could reduce emissions, like cap-and-trade systems and carbon taxes. But these people were members of the elite toying with equations that could not possibly include all the relevant factors, and who were vulnerable to their elite biases. So the United States decided to leave the decision up to democratic mechanisms, which allowed people to contribute “outside-the-system” insights like “Actually global warming is fake and it’s all a Chinese plot”.

5. Coronavirus lockdowns: The government appointed a set of supposedly infallible scientist-priests to determine when people were or weren’t allowed to engage in normal economic activity. The scientist-priests, who knew nothing about the complex set of factors that make one person decide to go to a rock festival and another to a bar, decided that vast swathes of economic activity they didn’t understand must stop. The ordinary people affected tried to engage in the usual mechanisms of democracy, like complaining, holding protests, and plotting to kidnap their governors – but the scientist-priests, certain that their analyses were “objective” and “fact-based”, thought ordinary people couldn’t possibly be smart enough to challenge them, and so refused to budge.

Nobody uses the word “technocrat” except when they’re criticizing something. So “technocracy” accretes this entire language around it – unintended consequences, the perils of supposed “objectivity”, the biases inherent in elite paradigms. And then when you describe something using this language, it’s like “Oh, of course that’s going to fail – everything like that has always failed before!”

But if you accept that “technocracy” describes things other than Soviet farming, Brasilia, and Robert Moses, the trick stops working. You notice a lot of things you could describe using the same vocabulary were good decisions that went well. Then you have to ask yourself: is Seeing Like A State the definitive proof that technocratic schemes never work? Or is it a compendium of rare man-bites-dog style cases, interesting precisely because of how unusual they are?

I want to make it really clear that I’m not saying that technocracy is good and democracy is bad. I’m saying that this is actually a hard problem. It’s not a morality play, where you tell ghost stories about scary High Modernists, point vaguely in the direction of Brasilia, say some platitudes about how no system can ever be truly unbiased, and then your work is done. There are actually a bunch of complicated reasons why formal expertise might be more useful in some situations, and local knowledge might be more useful in others.

November 10, 2020

The amazing mental gymnastics that lead to the US Supreme Court’s unanimous decision in Wickard v. Filburn in 1942

Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan explain how a farmer growing wheat on his own land to feed his own cattle somehow transmogrified into an interstate commerce activity that could be regulated by the federal government:

Panorama of the west facade of United States Supreme Court Building at dusk in Washington, D.C., 10 October, 2011.

Photo by Joe Ravi via Wikimedia Commons.

… who ended up being tasked with deciding what Article One, Section Eight actually meant? Herein lies the wrinkle that enables all manner of constitutional mischief in the United States. The institution that ended up deciding what the federal government is empowered to do is itself a branch of the federal government. And it should come as no surprise that when push comes to shove, the Supreme Court routinely finds in favor of empowering the federal government.

This sort of mischief flowered fully in the decade following ratification of the 21st Amendment. In 1942, the Supreme Court decided a case, Wickard v. Filburn, in which farmer Roscoe Filburn ran afoul of a federal law that limited how much wheat he was allowed to grow.

A careful reader might, and should, ask where the federal government’s right to legislate the wheat market is to be found — because the word “wheat” is nowhere to be found in the Constitution. Be that as it may, the federal government’s aim was clear enough. It was to keep the price of wheat high enough for farmers to remain profitable. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 put an upper limit on how much wheat farmers were allowed to grow, which would serve to keep prices high by limiting supply.

Roscoe Filburn had grown 12 more acres of wheat than the law allowed. But not only did he not sell the excess wheat outside of his home state, but he also didn’t sell it at all. He used the wheat from those 12 acres to feed his cattle. Filburn was very clearly not engaging in commerce, let alone interstate commerce, yet the Supreme Court found (unanimously) that because Congress had the authority to regulate interstate commerce, Congress also had the authority to prohibit Filburn from growing those 12 acres of wheat for his own use. The Supreme Court’s “reasoning”?

Had Filburn not fed his cattle that excess wheat, he would have been forced to purchase wheat on the open market. And even if he purchased wheat that was grown within his home state, doing so would have made less wheat available within his home state for other wheat buyers. Consequently, some wheat buyers within his home state would then have had to buy wheat from outside the state. Therefore, Filburn’s non-commercial activity was, according to the Supreme Court, interstate commerce.

The mental gymnastics that went into this ruling made just about any activity interstate commerce by definition. Since Wickard, any time Congress has wanted to exercise power not authorized by the Constitution, lawmakers have simply had to make an argument that links whatever they want to accomplish to interstate commerce. Why? Because they know they can get away with it.

October 15, 2020

This is what happens when politicians delegate too much of their powers to the courts

At the Foundation for Economic Education, Lawrence W. Reed recounts the stunning injustice of Soviet “justice”, in the person of Nikolai Krylenko:

Panorama of the west facade of United States Supreme Court Building at dusk in Washington, D.C., 10 October, 2011.

Photo by Joe Ravi via Wikimedia Commons.

As I watched the first day of hearings on Judge Barrett’s nomination, I was reminded of a largely forgotten Soviet legal theoretician from decades ago. His name was Nikolai Krylenko. Judge Barrett is being given the Krylenko treatment by Democrat senators like Cory Booker and Kamala Harris, meaning this: The only thing that matters is whether she will vote their party line in future cases.

Under the communist dictatorship of Lenin and then Stalin, Krylenko (1885-1938) rose through the Soviet Union’s legal system to become People’s Commissar for Justice and a Prosecutor General. He was a leading practitioner of the theory of “socialist legality,” which held that an accused person’s innocence or guilt depended on that person’s politics (real or imagined). It sounds nuts and indeed, it was. It was the stuff of Orwell’s nightmare, and one of the reasons the Soviet Union thankfully perished of its own poison.

In The Gulag Archipelago, the famous Soviet dissident and Nobel laureate Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn recounted an episode involving Krylenko. Shortly after Lenin’s Bolsheviks assumed power in 1917, an admiral named Shchastny was sentenced by one of the regime’s judges “to be shot within 24 hours.” When some in the courtroom expressed shock, it was Krylenko who responded thusly: “What are you worrying about? Executions have been abolished. But Shchastny is not being executed; he is being shot.”

To Krylenko, the only morality was what served the Party and the State, which of course in the Soviet Union were one and the same. If your politics were not correct, you would be “corrected,” one way or the other. In Richard Pipes’ authoritative book, The Russian Revolution, Krylenko is quoted as exclaiming, “We must execute not only the guilty. Execution of the innocent will impress the masses even more.”

At the Senate hearings for the Barrett nomination, it was apparent the first day that the Judge was being Krylenkoed. Hostile senators pronounced their verdicts before she had uttered a word, and those verdicts had nothing to do with Barrett’s stellar qualifications or keen legal mind. Legal analyst and George Washington University Law School professor Jonathan Turley commented,

What they were suggesting is that they will be voting against her because of what they expected her vote would be in a pending case, and that is a conditional confirmation … Here, the senators seem to be saying, “I’m not even going to listen; I’m going to vote against you because I don’t think you’re going to vote the right way …”

Judge Barrett clearly articulated her judicial philosophy, borne out by the way she has ruled at the US Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit: She believes the role of a judge or justice is to follow the Constitution and the law as written, not make stuff up in the service of a political agenda. How ironic that this is a point of fiery contention. Senators who swore an oath to uphold the Constitution and the law hate the guts of a judge who does just that!

October 2, 2020

The “Catch-22” in RBG’s majority opinion in City of Sherrill V. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y.

In The Line, Meaghie Champion outlines the awkward position the Oneida First Nation found itself in after their case made it to the US Supreme Court:

Panorama of the west facade of United States Supreme Court Building at dusk in Washington, D.C., 10 October, 2011.

Photo by Joe Ravi via Wikimedia Commons.

In 2005, in the case of the City of Sherrill V. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y., the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Oneidas, after the nation had attempted to assert sovereignty in traditional land they had to re-purchase after it had been illegally acquired.

Writing the majority position was the late liberal figurehead now being lionized in U.S. media — Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Granted, she fought for women’s rights and accomplished a lot. She was a law school professor and a judge. She was one of the leaders of the American Civil Liberties Union. She was the second woman to ever serve on the United States Supreme Court. She was influential in a lot of cases on the Supreme Court, including a labour law case that inspired a law to be passed, and an environmental case that set new standards for who could be heard in court on environmental issues. Since her recent death, the news coverage has been singing her praises like hagiography.

But study history and you will find lots of villains, and no saints. Many First Nations people in North America look on Ginsburg’s reification with a much more skeptical eye.

Meanwhile, the sovereignty of many Indigenous nations in B.C. has never been extinguished. Many First Nations here are being corralled into signing treaties that give up lands, rights and sovereignty. They may look to the Oneida as a cautionary tale. When it comes to sovereignty, you must use it or lose it. Don’t look to courts to give it back later. Not even when you have a social justice saint for a judge.

Ginsburg ruled that Indian land in central New York acquired in violation of U.S. federal law, a treaty, and the U.S. Constitution, could not be reintegrated into the ancestral lands of the Oneida Indian Nation — that the Oneidas would be required to pay property taxes to the local government of the City of Sherill. That is, unless the Oneidas sacrificed that land and allowed the federal government to administer it as a trust.

Justice Ginsburg wrote that 200 years had passed since the initial illegal acquisition, the land had passed hands between jurisdictions multiple times over the period, and that the Oneida had just waited too long. (Even though the U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged in 2005 that there was no specific time limit on this kind of case.) She claimed in her opinion that it would just be “unfair” to the non-natives in this case. If the Oneida had sued in court sooner, then it would have been different.

In the long and fraught web of relationships between First Nations and the United States government, it’s hard to pick a time before the late 20th century or early 21st where a First Nations case might be given full and fair hearing by any federal court, which shows Ginsburg’s opinion to be … lacking in historical sensitivity.

October 1, 2020

Supreme Court Shenanigans!

September 21, 2020

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, RIP

David Warren notes the passing of US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg at a particularly fraught moment in US political history:

US Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia.

Screencap from a report by CBS News.

The death of the prominent American jurisprude, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, will be this morning’s example. I noticed that a favoured rightwing blog said, “Breaking news. Try to show some respect for the dead.” This comes more easily to a human being, if he is at least superficially decent. Self-discipline may make it possible for others.

Mrs Ginsburg was toward the left side of the Supreme Court in Washington, in her rulings and often articulate dissents, but I loved her anyway. So did the late Antonin Scalia, who when he died inspired real grief to exponents of the other side. They were notorious buddies, Ginsburg and Scalia. They were more than willing to hear each other out; neither was a hothead. Both were deeply informed about Yankee law, and human law generally, unlike most judges. They could discuss its principles at a high level; and at a low, with a sense of humour. Their mutual respect set an example in their vicinity, claquers who included other Court members. They were both utterly worth having at their stations.

One wonders if those days are gone, for the foreseeable future, when some degree of civilization was possible in legal and political debate. When I look instead at electoral campaigns, in which knowing, malicious lies are repeated by both sides, and both are trying to raise the temperature (I won’t say “equally”), I see something larger than the current political issues. We cannot have public order if this continues; only tyranny can be imposed by one side. Mistakes are being made by “my side,” when we forget that daily life requires negotiation. Or rather it doesn’t, if one prefers civil war.

August 26, 2020

QotD: The U.S. Supreme Court

During almost every Supreme Court nomination battle, I try to make the same point: These fights wouldn’t be nearly so ugly if we didn’t invest so much power in the Supreme Court it shouldn’t have in the first place.

Until the Robert Bork nomination in 1987, Supreme Court fights were remarkably staid affairs. But by the late ’80s, the court had become a bulwark for all sorts of policies and laws that should rightly be in the portfolio of the legislative or executive branch, or, better, left to the various states. As a result, on any number of issues — most conspicuously abortion policy — the court became more important than the presidency or Congress. No wonder fights over Supreme Court appointments started to look more and more like political campaigns than debates over the finer points of judicial philosophy.

Jonah Goldberg, “Concentrated Power Inevitably Leads to Political Backlash”, Townhall.com, 2018-05-11.

July 11, 2020

Truncating the state of Oklahoma

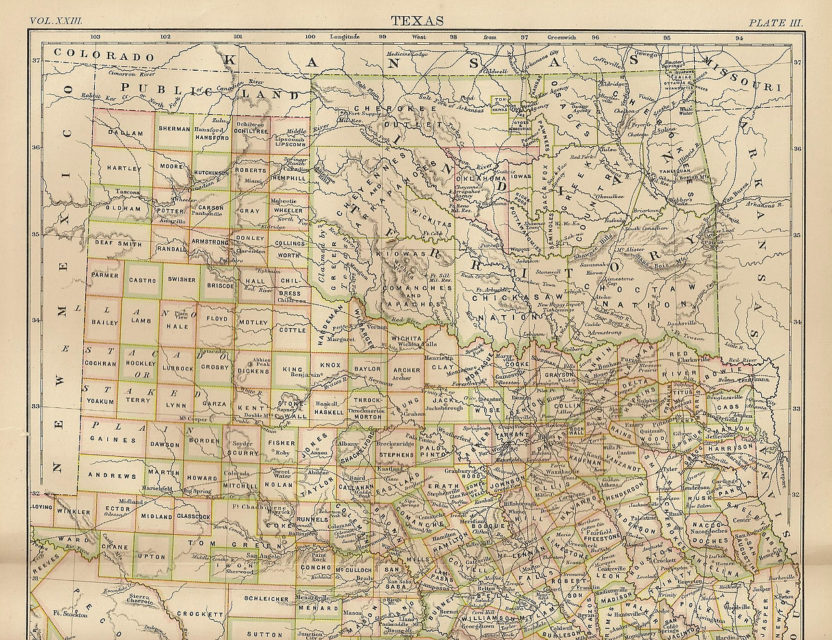

Colby Cosh on what might turn out to be the most important US Supreme Court decision in recent history:

A map of Oklahoma from the mid-1880s showing county boundaries and the tribal areas of Indian Territory.

Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th edition, 1888 via Wikimedia Commons.

On Thursday the court published its judgment in the case of McGirt v. Oklahoma [PDF]. McGirt is Jimcy McGirt, a man convicted in state court in 1997 of heinous sex crimes against a four year old. A creative public defender had tried to argue for years in lower courts that, as McGirt was a member of the Seminole Nation and his crimes had occurred on territory set aside in the 19th century for Creek Indians, he was never subject to state prosecution.

He should have been tried, the argument ran, under the federal Major Crimes Act of 1885, which specifies that accusations of serious felonies against Indians in “Indian country” go immediately to federal court. Under an 1856 treaty between the U.S. and the Creeks, the Creek lands were to be a “permanent home” for the displaced nation for as long as it existed (at a time when Aboriginal-Americans were still widely expected to diminish and disappear as a race).

The formalized concept of an Indian reservation did not yet exist, but the theory, then and now, is that some Aboriginal nations have direct relationships, albeit ones of “dependence,” with the federal government. Sometimes it is said that the U.S. is the “suzerain,” the overlord, of otherwise sovereign Indian nations. The Creeks, and the other four “Civilized Tribes” who had been forced into the “Indian Territory” that once covered the eastern part of future Oklahoma, were given strong written promises that they would be held apart from the U.S. states proper and would have jurisdiction over crimes and civil matters on their lands. Only the United States Congress, as a power contracting with sovereign nations, could act to encroach upon this jurisdiction.

In a fashion familiar to anyone who has read even a shred of the history of the American Indian, these promises just kind of got … misplaced. In the early 20th century the Oklahoma tribes were encouraged by Congress to abandon communal property holding and take up individual “allotments” of Indian-held land. This ought not to have changed the underlying nation-to-nation relationship, any more than assigning homesteading parcels to settlers busted up or negated the ultimate sovereignty of the U.S. elsewhere in the American West. But that constitutional framework was more easily ignored once a contiguous bundle of territory began to be bought and sold. (Some of it became part of the city of Tulsa.) This history has helped to make similar allotment action in Canada impossible, whatever advantages it might have.

January 19, 2020

“… if the Constitution is a threat to killer whales, why, then, to hell with the Constitution”

Colby Cosh reviews the sad tale of the British Columbian government’s defeat before the Supreme Court of Canada over pipelines:

“Supreme Court of Canada, Ottawa” by daniel0685 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

So … yeah, that didn’t go real well. On Thursday the province of British Columbia sent its chosen representative, lawyer Joseph Arvay, to the Supreme Court to plead the oral case for B.C.’s law regulating bitumen in pipelines. John Horgan’s government had attempted to establish its own permit regime for pipeline contents, which are, under accepted constitutional doctrine, a federal responsibility. The B.C. Court of Appeal had wiped out the provincial law unanimously last summer.

Arvay’s task was widely recognized as a Hail Mary pass. But things got even more awkward as the hearing commenced and the justices of the Supreme Court interrogated him on his province’s logical, environmental, and even economic premises. An appellate court’s disposition is sometimes hard to ferret out in its hearings, but this one was so rough that Arvay was reduced to grumbling “If I’m not going to win the appeal, then I don’t want to lose badly.” Alas, the judges did not even see the need to deliberate over their reasons: they at once, and as one, ruled against B.C.

Which is not to suggest that Mr. Arvay didn’t do the best possible job. If we’re sticking with the football metaphor, the problem all along was the game plan. Given the clear federal responsibility for interprovincial pipelines, as “Works and Undertakings connecting … Provinces,” the B.C. government had no choice but to downplay the conflict between the purpose of its proposed environmental permits and the purpose of the ones the federal government hands out. Arvay had to try to convince the ermine gang that a law applying exclusively to the contents of a pipeline wasn’t a regulation of the pipeline.

“The only concern the premier, the attorney general and the members of the government have had is the harm of bitumen,” Arvay protested. “It’s not about pipelines. They’re not anti-pipelines, they’re not anti-Alberta, they’re not anti-oilsands, they’re not anti-oil.”

It’s enough to almost make one sympathetic to the more radical strategy of argument pursued at the hearing by Harry Wruck, a lawyer for Ecojustice Canada who appeared as an intervener supporting B.C. Wruck put before the Supreme Court the same idea he had presented to the BCCA: if the Constitution is a threat to killer whales, why, then, to hell with the Constitution.

December 8, 2019

The “Church of Atheism” doesn’t get charitable status … this time

Colby Cosh on the recent court decision on the Church of Atheism’s attempt to qualify as a church — and receive the tax benefits — under Revenue Canada’s rules:

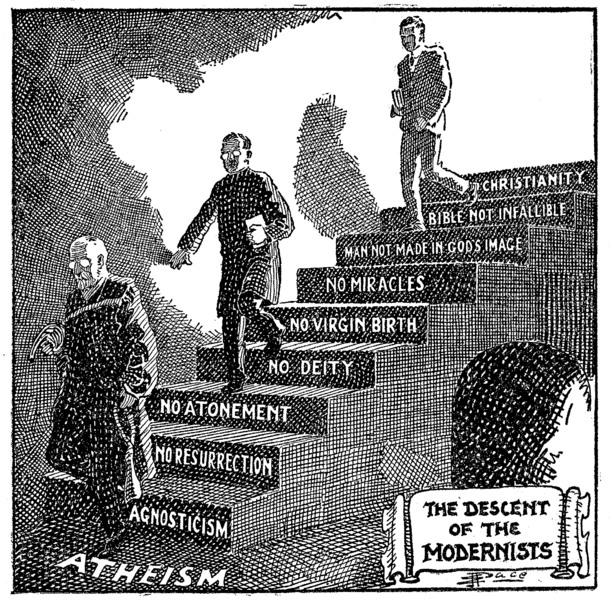

“The Descent of the Modernists”, by E.J. Pace, first appearing in his book Christian Cartoons, published in 1922.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Last week the Federal Court of Appeal upheld Revenue Canada’s rejection of an application for charitable status made by a “Church of Atheism” tucked away in Ontario’s Lanark Highlands. The idea of making a gesture like this has probably occurred to every atheist who looks around at a world of tax-exempt churches and wonders why his kind is excluded from the gravy train. (Clergymen pay tax on their income, but they have access to a generous residential deduction, and any professional expenses covered by the church go untaxed.)

The fact is that the “Church’s” efforts were a bit amateurish and confused. But they may, like a doomed military reconnaissance, have revealed weaknesses in the anomalous exclusion of atheists from religious tax exemptions.

These weaknesses cannot be any big secret. You probably remember the Supreme Court’s Mouvement laïque québécois v. Saguenay decision of 2015 — that’s the case in which the Quebec Court of Appeal had ruled that a statue of Christ with an electrically illuminated Sacred Heart was “devoid of religious connotation.” The Supreme Court, perhaps suppressing a chuckle or two, proceeded to unanimously overturn the Quebec ruling and expound the concept that the Canadian state has a Charter-based “duty of religious neutrality” (except, of course, where the constitution explicitly specifies otherwise, as with Catholic schools). Government, the SCC insisted, “must neither favour nor hinder any particular belief, and the same holds true for non-belief.”

Given that this is our law, what can be the problem with a “Church of Atheism”? Good question! Justice Marianne Rivoalen, writing on behalf of a three-judge Federal Court panel, confirmed the general point that there is a state duty of religious neutrality; in fact, even Revenue Canada, acting as the respondent, conceded this.

But the court simply ruled, without any logical elucidation, that “the Minister (of Revenue)’s refusal to register the appellant as a charitable organization does not interfere in a manner that is more than trivial or insubstantial with the appellant’s members’ ability to practise their atheistic beliefs. The appellant can continue to carry out its purpose and its activities without charitable registration.”

October 27, 2019

Freedom of speech under threat (again)

In The Atlantic, Ken White strongly urges pro-free-speech advocates to avoid using some arguments that have been bandied around recently:

What speech should be protected by the First Amendment is open to debate. Americans can, and should, argue about what the law ought to be. That’s what free people do. But while we’re all entitled to our own opinions, we’re not entitled to our own facts, even in 2019. In fact, the First Amendment is broad, robust, aggressively and consistently protected by the Supreme Court, and not subject to the many exceptions and qualifications that commentators seek to graft upon it. The majority of contemptible, bigoted speech is protected.

If you’ve read op-eds about free speech in America, or listened to talking heads on the news, you’ve almost certainly encountered empty, misleading, or simply false tropes about the First Amendment. Those tired tropes are barriers to serious discussions about free speech. Any useful discussion of what the law should be must be informed by an accurate view of what the law is.

[…]“This speech isn’t protected, because you can’t shout ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater.”

This line, though ubiquitous, is just another way to convey that “not all speech is protected by the First Amendment.” As an argument, it is just as useless.

But the phrase is not just empty. It’s also a historically ignorant way to convey the point. It dates back to a 1919 Supreme Court decision allowing the imprisonment of Charles Schenck for urging resistance to the draft in World War I. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. wrote that the “most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.” This decision led to a series of cases broadly endorsing the government’s ability to suppress speech that questioned official policy. But for more than half a century Schenck has unequivocally and universally been acknowledged as bad law.

Holmes himself repented of the decision — though he continued to indulge his taste for pithy phrases with lines like “Three generations of imbeciles are enough” to justify forcible government sterilization of the handicapped.

So when you smugly drop “You can’t shout ‘Fire!’ in a crowded theater” in a First Amendment debate, you’re misquoting an empty rhetorical device uttered by a career totalitarian in a long-overturned case about jailing draft protesters. This is not persuasive or helpful.

September 27, 2019

England’s constitution before the shiny new Supreme Court was created

Peter Hitchins provides a thumbnail sketch of the state of play before the Supreme Court was added to British constitutional arrangements:

“Palace of Westminster” by michaelhenley is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Why did we never even have such a body until ten years ago? As we shall see, it would have been, and still is, a contradiction in terms. But in interesting times such as these, elephants fly, fishes walk, figs grow on thorns, and oxymorons inherit the earth.

The most powerful law court in the land was, by a curious paradox, not in the land at all, but based in tiny Luxembourg, across the Narrow Seas which have kept invaders from our door but are useless against bureaucratic takeovers by the European Union. There sits the European Court of Justice, which as long ago as 1990 established that it could tell British courts to overrule British Acts of Parliament when they conflict with E.U. law. It can carry on doing this until we eventually do leave the E.U., if we ever do.

These various messes came about because we are so old, and rely so much on convention and manners, that it is all too easy for unconventional and ill-mannered busybodies to come storming in with new ideas. England’s constitution was not planned and built, like America’s. Instead, it grew during a thousand years of freedom from invasion. Both are beautiful in their way. America’s fundamental law has the cold, orderly beauty of a classical temple. England’s has the warmer, more chaotic loveliness of an ancient forest. It seems to be wholly natural but, when examined closely, it shows many signs of careful cultivation and pruning. Our powers are not as separated as America’s, but slightly tangled. Still, it has worked well enough for us over time.

Any thinking person must admire both the American and the English constitutions as serious efforts in a world of chaos, despotism, and stupidity to apply human intelligence to the task of giving people ordered, peaceful, and free lives. They have a common origin in the miraculous Magna Carta, which Americans often revere more than modern Englishmen do. We in England have grown complacent about our liberty, and have become inclined to forget our great founding documents.

But the two constitutions are not the same, and in my view they are not compatible. For my whole life, until a few years ago, the very idea that England should have a Supreme Court was an absurdity. The Highest Court in England is the Crown in Parliament which, as I was once taught, had the power to do everything except turn a man into a woman. In these more gender-fluid times, that expression is not much used. But it contains the truth. Parliament can make any law and overturn any law, made by itself or by the courts.

That is why England (often to my regret) lacks a First Amendment and cannot have one unless we undergo a revolution. No law in England could possibly open with the words “Parliament shall make no law.” Our 1689 Bill of Rights, the model for the U.S. Bill of Rights a century later, tells the king what he cannot do and the courts what they cannot do. It grants me (as a Protestant) the right to have weapons for my defense. But while it draws its sword against arbitrary power, it puts a protective arm round Parliament.