World War Two

Published 16 Sep 2023The Japanese attacks in Guangxi worry Joe Stilwell enough that he gets FDR to issue an ultimatum to Chiang Kai-Shek, in France the Allied invasion forces that hit the north and south coasts finally link up, the Warsaw Uprising continues, and the US Marines land on Peleliu and Angaur.

(more…)

September 17, 2023

The Ballad of Chiang and Vinegar Joe – WW2 – Week 264 – September 16, 1944

Why Operation Market Garden Failed and Its Devastating Consequences

OTD Military History

Published 5 Apr 2023Why did Operation Market Garden fail and what were the consequences of this failure? This video covers the operation, the reasons for the failure, and its devastating aftermath. The impact Market Garden had on the Dutch during the Hunger Winter and Allied soldiers during the Battle of the Scheldt is explored.

There is footage of the 101st US Airborne, 82nd US Airborne, British 1st Airborne Division, and the troops of the British XXX Corps featured in the video.

(more…)

September 15, 2023

Learning to handle mules to accompany Chindit columns in WW2

Robert Lyman posted some interesting details from veteran Philip Brownless of how British troops in India had to learn how to handle mules and abandon their motor transport in order to get Chindit columns into Japanese territory in Burma:

Soon after our return from the Arakan front in the autumn of 1943, we were in central India, and had been told that the whole division was to be handed over to General Wingate and trained to operate behind the Japanese lines. All our motor transport was to be taken away and we were to be entirely dependent upon mules for our transport.

The C.O. one evening looked round the mess and then said to me “You look more like a country bumpkin than anybody else. You will go on a veterinary course on Tuesday and when you come back you will take charge of 44 Column’s mules.”

I had never met one of these creatures before. On arriving at Ambala I reported to the Area Brigade Major who wasn’t expecting me and seemed to have no clue about anything. He said “You’d better go down to the Club and book in”. I reported to the Club, a comfortable looking establishment, and they seemed to have a vague idea that a few bodies like me might turn up on a course and were apologetic that I would have to sleep in a tent but otherwise could enjoy the full facilities of the Club. I was shown the tent, an EPIP tent or minor marquee, with a coloured red lining and golden fleur de lys all over it, (very Victorian) with a small office extension with table and chair in front and another extension at the back with bath, towel rail and a fully bricked floor. Having lived either in a tent or under the stars in both the desert and the Arakan for the last 2 years, this struck me as luxury indeed. Even better, I took on a magnificent bearer, with suitable references, whom I found later was some kind of Hindu priest. I soon got used to having my trouser legs held up for me to put my feet in, and being helped into the rest of my clothes. I had a comfortable 3 weeks learning all about mules.

I discovered all sorts of things like the veterinary term “balls”, which were massive pills which were given to the mule by – first of all grabbing his tongue and pulling it out sideways so he couldn’t shut his mouth on your arm, and then gently throwing the ball at his epiglottis and making sure it went down. Then you let go of his tongue and gave him a nice pat. One of our lecturers, an Indian warrant officer, knew his stuff well and was so pleased about it that when he asked a question he would give you the answer himself. He liked being dramatic and loved to finish a description of some fatal ailment by saying “Treatment, bullet”.

Many of the men in our battalion were East Enders; others came from all over Essex. A few were countrymen, two were Irish and knew all about horses, one sergeant had been in animal transport and one invaluable soldier had been an East End horse dealer. The large majority had had nothing to do with animals: however, the saving grace was that English soldiers seem to be naturally good with animals and soon learned to handle them well. I arranged to get some instruction from the nearby unit of Madras Sappers and Miners and we borrowed a handful of trained mules from them for the men to practise handling, tying on loads and learning to talk to them.

Then came the great day when we were to draw up our main complement of animals, about 70 mules and 12 ponies. We were dumped at a small railway station. It was all open ground and there was a team of Army Veterinary Surgeons to allocate fairly between the three battalions, the Essex, the Borders and the Duke of Wellington’s. Lieut. Jimmy Watt of the Borders was a pal of mine: he and I, with a squad of men were to march them back nearly 100 miles to our camp, sleeping each of the five nights under the stars. As soon as we arrived at the disembarkation site I got all our mule lines laid out, with shackles (used to tie mules fore and aft) and nosebags ready. I had also picked up the tip that the mules would be wild, having spent three days in the train, and almost impossible to hold, so I instructed our men to tie them together in threes before they got off the train. As all three pulled in different directions, one muleteer could hold them. Not everybody had learned this trick so the result was that wild mules were careering all over the place, impossible to catch. When our first handful of mules arrived, they were quickly secured in a straight line and fed. They were familiar with lines like this and cooled down at once, long ears relaxed and tails swishing amiably. When the wild mules careering round saw this line, they said to themselves “We’ve done this before” and came and stood in our lines. We shackled them and I picked out the moth-eaten ones and sent them back to the vets who kept sending polite messages of thanks to Mr. Brownless for catching them. We finished up with a very good set of mules. Jimmy Watt and I had a bit of a conscience about the Duke of Wellington’s so we picked them out a really good pony. We felt even worse a few weeks later when it was sent back to Remounts with a weak heart! The Brigade Transport Officer visited us the second evening so Jimmy Watt and I walked him round rather quickly, chatting hard, to approve the allocation of animals, and he agreed with our arrangement.

In a highly optimistic mood early on, I decided to practise a river crossing. We marched several miles out from camp to a typical wide sandy Indian river, 300 yards across, made our preparations, i.e. assembling the two assault boats, making floating bundles of our clothes and gear by wrapping them in groundsheets, unsaddling the animals, and assembling at the water’s edge. A good sized detachment of muleteers was posted on the opposite bank ready to catch the mules. The mules waded into the shallow water but no one could get them to move off. We tried all sorts of inducements in vain and then suddenly, one sturdy little grey animal decided to swim and the whole lot immediately followed. Calamity ensued! Mules are very short sighted and could only dimly see the opposite bank but downstream was a bright yellow sandy outcrop and they all made for this. The muleteers on the other bank, when they realised what was happening, ran through the scrub and jungle as fast as they could, but the mules arrived first and bolted off into the wilds of India. I swam my pony across with my arm across his withers and directing him by holding his head harness, the gear was ferried across and the mule platoon, with one pony, began the march back to camp. Deeply depressed, I wondered how to tell the C.O. I had lost all his mules and imagined the court martial which awaited me (or, serving under General Wingate, would I be shot out of hand?) An hour and a half later we came in sight of the camp and to my utter astonishment I could see the mules in their lines. When I arrived at the mule lines, the storeman met me and said that the whole lot had arrived at the double and had gone to their places. He had merely gone along the lines, shackling them and patted their noses. Salvation! I kept quiet for a bit but it got out and I was the butt of much merrymaking.

September 8, 2023

Johnson M1941 rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 8 Dec 2013Melvin Johnson was a gun designer who felt that the M1 Garand rifle had several significant flaws — so he developed his own semiauto .30-06 rifle to supplement the M1. His thought was that if problems arose with the M1 in combat, production of his rifle could provide a continuing supply of arms while problems with the M1 were worked out. The rifle he designed was a short-recoil system with a multi-lug rotating bolt (which was the direct ancestor of the AR bolt design). When the Johnson rifle was tested formally alongside the M1, the two were found to be pretty much evenly matched — which led the Army to dismiss the Johnson. If it wasn’t a significant improvement over the Garand, Ordnance didn’t see the use in siphoning off resources to produce a second rifle.

The Johnson had some interesting features — primarily its magazine design. It used a fixed 10-round rotary magazine, which could be fed by 5-round standard stripper clips or loose individual cartridges. It could also be topped up without interfering with the rifle’s action, unlike the M1. On the other hand, it was not well suited to using a bayonet, since the extra weight on the barrel was liable to cause reliability problems (since the recoil action has to be balanced for a specific reciprocating mass). Johnson thought bayonets were mostly useless, but the Army used the issue as a rationale to dismiss the Johnson from consideration.

However, Johnson was able to make sales of the rifle to the Dutch government, which was in urgent need of arms for the East Indies colonies. This is where the M1941 designation came from — it was the Dutch model name. Only a few of the 30,000 manufactured rifles were delivered before the Japanese overran the Dutch islands, rendering the rest of the shipment moot.

At this point, Johnson was also working to interest the newly-formed Marine Paratroop battalions in a light machine gun version of his rifle. The Paramarines needed an LMG which could be broken down for jumping, light enough for a single man to effectively carry, and quick to reassemble upon landing. The Johnson LMG met these requirements extremely well, and was adopted for the purpose. The Paramarines were being issued Reising folding-stock submachine guns in addition to the Johnson LMGs, and they found the Reisings less than desirable. Someone noticed that thousands of M1941 Johnson rifles (which could also have their barrel quickly and easily removed for compact storage) were effectively sitting abandoned on the docks, and the Para Marines liberated more than a few of them. These rifles were never officially on the US Army books, but they were used on Bougainville and a few other small islands.

September 2, 2023

Trial Run for D-Day – Allied Invasion of Sicily 1943

Real Time History

Published 1 Sept 2023After defeating the Axis in North Africa, the stage was set for the first Allied landing in Europe. The target was Sicily and in summer 1943 Allied generals Patton and Montgomery set their sights on the island off the Italian peninsula.

(more…)

August 29, 2023

A Rare World War One Sniper’s Rifle: Model 1916 Lebel

Forgotten Weapons

Published 28 Feb 2018Unlike Great Britain and Germany, the French military never developed a formal sniper doctrine during World War One — they had no dedicated schools or instruction manuals for that specialty. The three major arsenals did produce scoped sniping rifles, however, with models of 1915, 1916, and 1917 (and a post-war 1921 pattern). We have a model 1916 example here today.

The rifles were completely ordinary off-the-rack Lebels, modified simply to add scope mounts. The 1916 pattern mount used a round peg on the side of the rear sight and a bracket wrapped around the front of the receiver, which allowed the scope to be quickly and easily detached for carry in a separate pouch (similar to what other nations did, to protect the optic from damage when not in use). The rifles were issued only in small numbers (2 per company, or even 2 per battalion) and it was left to the unit commander to decide how to employ them.

This particular scope has some neat provenance of being brought home by a US soldier after the war — it came back wrapped in a period copy of Stars and Stripes magazine. The rifle is of the appropriate type, but the “N” marks on the barrel and receiver indicated French overhaul in the 1930s, precluding it from being the original rifle this scope was mounted on.

(more…)

August 26, 2023

OSS “Bigot” 1911 dart-firing pistol

Forgotten Weapons

Published 2 Apr 2012The “Bigot” was a modification of an M1911 .45 caliber pistol developed by the Office of Strategic Services during WW2. The OSS was a clandestine operations service, the predecessor of the CIA. The Bigot was intended as a way for commandos to quietly eliminate sentries — although we are not sure what advantage it might have had over a silenced pistol. Questionable utility doesn’t prevent it from being a pretty interesting piece of equipment, though, and we had the opportunity to take a look at one up close recently.

August 19, 2023

One Day in August – Dieppe Anniversary Battlefield Event (Operation Jubilee)

WW2TV

Published 19 Aug 2021One Day in August — Dieppe Anniversary Battlefield Event (Operation Jubilee) With David O’Keefe, Part 3 — Anniversary Battlefield Event.

David O’Keefe joins us for a third and final show about Operation Jubilee to explain how the plan unravelled and how the nearly 1,000 British, Canadian and American commandos died. We will use aerial footage, HD footage taken in Dieppe last week and maps, photos, and graphics.

In Part 1 David O’Keefe talked about the real reason for the raid on Dieppe in August 1942. In Part 2 David talked about the plan for Operation Jubilee. The intentions of the raid and how it was supposed to unfold.

(more…)

Dieppe Raid – 19 August, 1942

The History Chap

Published 15 Aug 2021The Dieppe Raid (codename Operation Jubilee) was a disastrous amphibious landing by the allies in France during World War 2. Nearly 4,000 allied soldiers (mainly Canadians) were killed, wounded or captured during the Battle of Dieppe.

1942 was turning out to be a bad year for the allies. The Nazis were sweeping forwards in Russia, the Japanese were sweeping though South East Asia. The British commonwealth troops were being pushed back by the Germans & Italians in North Africa and the Americans were still reeling from the attack on Pearl Harbour.

The British wanted to show that they were still willing to take the offensive in the war and were were being urged by Stalin to take some pressure off the Soviet Union. A plan was hatched to conduct a “smash & grab” raid on the port of Dieppe in northern France. The aim was to seize Dieppe and hold it for a limited time before evacuation, during which time the allied troops would collect intelligence and destroy German military infrastructure.

The Canadian government were keen to have their own troops play a role in the war and so the majority of the raiding force was made up of their troops. Initially planned for early July, Operation Jubilee was delayed for over a month due to bad weather and the need for a high tide at dawn. Eventually the Dieppe Raid took place just before 0400 on the 19th August 1942. 5,000 Canadians, 1,000 British and 50 US Rangers were to land at five different points along a 16km (10 mile front) either side of the port of Dieppe itself.

The result was a complete disaster. No major objectives were achieved, poor intelligence had not identified the strength of the German defences and the Germans were on high alert for a possible attack after the firefight at sea and the fact that there was high tide. Within less than 6 hours of the landing starting the order had been given to evacuate and by 1400 hours what remained of the allied force had been successfully removed.

The Dieppe Raid lasted 10 hours. They left behind 4,000 killed, wounded or prisoners of war — over 80% of whom were Canadians. The Royal Navy lost a destroyer and 33 landing craft whilst the RAF lost 106 planes.

The raid had sent a signal to the Germans that the Atlantic shoreline was not secure. That eventually they would have to fight the war on two fronts. It also raised morale within the population of occupied France. They were not alone. The best that can be said for the raid was that it taught the allies valuable lessons which were successfully implemented in the D-Day landings in Normandy in 1944. Maybe the sacrifice of the young men at Dieppe saved many more young men on D-Day.

(more…)

August 18, 2023

One Day in August – Dieppe – Part 2 – The Plan

WW2TV

Published 17 Jan 2021Part 2 – The Plan With David O’Keefe

David O’Keefe joins us again. In Part 1 he talked about the real reason for the raid on Dieppe in August 1942. In Part 2 we talk about the plan for Operation Jubilee and David will share his presentation about the intentions of the raid and how it was supposed to unfold.

A final show sometime in the summer will come live from Dieppe to explain how the plan unravelled and how the nearly 1,000 British, Canadian and American commandos died.

(more…)

August 17, 2023

Dieppe – One Day in August – Ian Fleming, Enigma and the Deadly Raid – Part 1

WW2TV

Published 29 Nov 2020In less than six hours in August 1942, nearly 1,000 British, Canadian and American commandos died in the French port of Dieppe in an operation that for decades seemed to have no real purpose. Was it a dry-run for D-Day, or perhaps a gesture by the Allies to placate Stalin’s impatience for a second front in the west?

Canadian historian David O’Keefe uses hitherto classified intelligence archives to prove that this catastrophic and apparently futile raid was in fact a mission, set up by Ian Fleming of British Naval Intelligence as part of a “pinch” policy designed to capture material relating to the four-rotor Enigma machine that would permit codebreakers like Alan Turing at Bletchley Park to turn the tide of the Second World War.

In this first show we will look at how the raid has been written about in previous books and the research David undertook and as importantly why he did it. In a future show, we will look at filming in Dieppe itself and explain the sequence of events.

(more…)

August 3, 2023

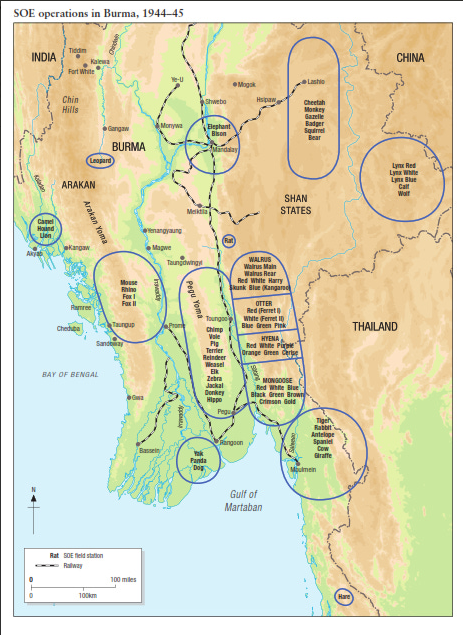

Behind Japanese lines in Burma – SOE and Karen tribal guerillas in 1944/45

Bill Lyman outlines one of the significant factors assisting General Slim’s XIVth Army to recapture Burma from the Japanese during late 1944 and early 1945:

If Lieutenant General Sir Bill Slim (he had been knighted by General Archibald Wavell, the Viceroy, the previous October, at Imphal) had been asked in January 1945 to describe the situation in Burma at the onset of the next monsoon period in May, I do not believe that in his wildest imaginings he could have conceived that the whole of Burma would be about to fall into his hands. After all, his army wasn’t yet fully across the Chindwin. Nearly 800 miles of tough country with few roads lay before him, not least the entire Burma Area Army under a new commander, General Kimura. The Arakanese coastline needed to be captured too, to allow aircraft to use the vital airfields at Akyab as a stepping stone to Rangoon. Likewise, I’m not sure that he would have imagined that a primary reason for the success of his Army was the work of 12,000 native levies from the Karen Hills, under the leadership of SOE, whose guerrilla activities prevented the Japanese from reaching, reinforcing and defending the key town of Toungoo on the Sittang river. It was the loss of this town, more than any other, which handed Burma to Slim on a plate, and it was SOE and their native Karen guerrillas which made it all possible.

In January 1945 Slim was given operational responsibility for Force 136 (i.e. Special Operations Executive, or SOE). It had operated in front of 20 Indian Division along the Chindwin between 1943 and early 1944 and did sterling work reporting on Japanese activity facing 4 Corps. Persuaded that similar groups working among the Karens in Burma’s eastern hills – an area known as the Karenni States – could achieve significant support for a land offensive in Burma, Slim authorised an operation to the Karens. Its task was not merely to undertake intelligence missions watching the road and railways between Mandalay and Rangoon, but to determine whether they would fight. If the Karens were prepared to do so, SOE would be responsible for training and organising them as armed groups able to deliver battlefield intelligence directly in support of the advancing 14 Army. In fact, the resulting operation – Character – was so spectacularly successful that it far outweighed what had been achieved by Operation Thursday the previous year in terms of its impact on the course of military operations in pursuit of the strategy to defeat the Japanese in the whole of Burma. It has been strangely forgotten, or ignored, by most historians ever since, drowned out perhaps by the noise made by the drama and heroism of Thursday, the second Chindit expedition. Over the course of Slim’s advance in 1945 some 2,000 British, Indian and Burmese officers and soldiers, along with 1,430 tons of supplies, were dropped into Burma for the purposes of providing intelligence about the Japanese that would be useful for the fighting formations of 14 Army, as well as undertaking limited guerrilla operations. As Richard Duckett has observed, this found SOE operating not merely as intelligence gatherers in the traditional sense, but as Special Forces with a defined military mission as part of conventional operations linked directly to a military strategic outcome. For Operation Character specifically, about 110 British officers and NCOs and over 100 men of all Burmese ethnicities, dominated interestingly by Burmans mobilised as many as 12,000 Karens over an area of 7,000 square miles to the anti-Japanese cause. Some 3,000 weapons were dropped into the Karenni States. Operating in five distinct groups (“Walrus”, “Ferret”, “Otter”, “Mongoose” and “Hyena”) the Karen irregulars trained and led by Force 136, waited the moment when 14 Army instructed them to attack.

Between 30 March and 10 April 1945 14 Army drove hard for Rangoon after its victories at Mandalay and Meiktila, with Lt General Frank Messervy’s 4 Indian Corps in the van. Pyawbe saw the first battle of 14 Army’s drive to Rangoon, and it proved as decisive in 1945 as the Japanese attack on Prome had been in 1942. Otherwise strong Japanese defensive positions around the town with limited capability for counter attack meant that the Japanese were sitting targets for Allied tanks, artillery and airpower. Messervy’s plan was simple: to bypass the defended points that lay before Pyawbe, allowing them to be dealt with by subsequent attack from the air, and surround Pyawbe from all points of the compass by 17 Indian Division before squeezing it like a lemon with his tanks and artillery. With nowhere to go, and with no effective means to counter-attack, the Japanese were exterminated bunker by bunker by the Shermans of 255 Tank Brigade, now slick with the experience of battle gained at Meiktila. Infantry, armour and aircraft cleared General Honda’s primary blocking point before Toungoo with coordinated precision. This single battle, which killed over 1,000 Japanese, entirely removed Honda’s ability to prevent 4 Corps from exploiting the road to Toungoo. Messervy grasped the opportunity, leapfrogging 5 Indian Division (the vanguard of the advance comprising an armoured regiment and armoured reconnaissance group from 255 Tank Brigade) southwards, capturing Shwemyo on 16 April, Pyinmana on 19 April and Lewe on 21 April. Toungoo was the immediate target, attractive because it boasted three airfields, from where No 224 Group could provide air support to Operation Dracula, the planned amphibious attack against Rangoon. Messervy drove his armour on, reaching Toungoo, much to the surprise of the Japanese, the following day. After three days of fighting, supported by heavy attack from the air by B24 Liberators, the town and its airfields fell to Messervy. On the very day of its capture, 100 C47s and C46 Commando transports landed the air transportable elements of 17 Indian Division to join their armoured comrades. They now took the lead from 5 Indian Division, accompanied by 255 Tank Brigade, for whom rations in their supporting vehicles had had been substituted for petrol, pressing on via Pegu to Rangoon.

July 10, 2023

Echoes of War: Accounts of Operation Husky and the Allied Landings in Sicily

OTD Military History

Published 9 Jul 2023On July 9/10 Allied forces launched Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily. This video presents accounts from various Allied military personnel who were there that day.

(more…)

July 8, 2023

The Perfect D-Day That History Forgot

Real Time History

Published 7 Jul 2023The summer of 1944 saw the Allies land in France not once but twice. Two months after Operation Overlord, the Allies also landed in Southern France during Operation Dragoon. It was “the perfect landing” and opened up the important ports of Marseille and Toulon for Allied logistics.

(more…)

July 7, 2023

Prototype Silenced Sten for Paratroops: the Mk4(S)

Forgotten Weapons

Published 24 Mar 2023The Sten Mk4 was developed experimentally in 1943 for use by British paratroops. It used a remarkably awful folding stock along with a shortened receiver and barrel to make a very compact package — albeit one that must have been very uncomfortable to shoot. Several different models were made, with this one being a Mk4a(S) — the suppressed version. The suppressor is essentially the same system as used on the MkII(S), but with the rear endcap and barrel being permanently fixed to the receiver of the gun.

Only a small number (allegedly 2000) Mk4 guns were originally made, and they were used for testing only — never for field service. Virtually all were destroyed after the war, with a few remaining examples in British museums. This one was amnesty registered in 1968, and is almost certainly the only one in private hands in the US (and possible the only privately owned one in the world).

The Mk4 was dropped in favor of the Mk5, which was a much more effective gun and was used by the British paratroopers in the late days of World War Two.

(more…)