… these same people want the government to provide them with free health care, and if they got their full way, other “positive liberties” (to quote Obama) including free college, free housing, free food, guaranteed income, guaranteed jobs.

[…] the moment all your necessities are furnished by someone else, someone else gets to make all the decisions for you. I mean, if your health is paid for by the taxes of your fellow citizens, and the government aka the nation looks after your every need: should they pay for your health if you insist on smoking or drinking? Or should those resources be husbanded for people who take better care of themselves? Okay, Sarah, but isn’t there a point to individual responsibility? Why shouldn’t you be required to take minimal care of yourself, so you get the benefits of the government’s care, which as you say someone else pays for.

Ah, but there’s the rub. See, ultimately, there’s always something some of us say or do that can be used to justify denying care or giving only palliative care. For instance, I’m overweight, which seems to be one of the remaining sins in the current lexicon. Sure, I gained tons of weight over 20 years of untreated hypothyroidism, even though I was starving myself for a long portion of those. But hey, I allowed myself to be overweight. So my prognosis is poor. Why spend money on me, when someone else could have better results?

Hell, even when it comes to my autoimmune. I’m a poor prospect, so why give me top of the line care?

If the government controlled other things, it would be exactly the same. Food? Sure, I break out in eczema all over when I eat a diet rich in carbs. But hey, flour and rice are cheap, and why should I get a specialized diet, since I’m only a writer who isn’t even a leftist or a supporter of the state, and besides my prospects of survival are poor?

College? Sure you want to be an economist, but your teachers say you’re cheeky and talk back, and the state doesn’t need that. What we need right now are pipe fitters. Here, you can take this six week course.

When the state is paying the bill, the state gets to decide what is better for you. The European constitution gives you the right to “death with dignity” because death with dignity is much cheaper than expensive treatments with a low chance of survival. After all this money is for everyone, you know?

And like the NHS, in Britain, they won’t even let you seek treatment outside their tender mercies. Why should they? They pay for you. That means in the end they decide what to spend on you. They own you. And if you went outside their system and your kid got cured? It would look pretty bad for them, wouldn’t it? Why should they allow you to do that? And besides, peasant, you have a bad attitude.

Sarah Hoyt, “Slouching Into Shackles”, According to Hoyt, 2018-04-27.

July 25, 2020

QotD: The real life implications of “positive” rights

July 6, 2020

The Healthcare Crisis of 1941 – WW2 – On the Homefront 005

World War Two

Published 2 Jul 2020When WWII breaks out many parts of the world are still missing population-wide healthcare. The pressure of the war deteriorates healthcare services even further. By 1941, both the British Commonwealth and Germany are facing an outright healthcare crisis on the home front.

Join us on Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TimeGhostHistory

Or join The TimeGhost Army directly at: https://timeghost.tvFollow WW2 day by day on Instagram @World_war_two_realtime https://www.instagram.com/world_war_two_realtime

Between 2 Wars: https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list…

Source list: http://bit.ly/WW2sourcesHosted by: Anna Deinhard

Written by: Fiona Rachel Fischer and Spartacus Olsson

Director: Astrid Deinhard

Producers: Astrid Deinhard and Spartacus Olsson

Executive Producers: Astrid Deinhard, Indy Neidell, Spartacus Olsson, Bodo Rittenauer

Creative Producer: Joram Appel

Post-Production Director: Wieke Kapteijns

Research by: Fiona Rachel Fischer

Edited by: Mikołaj Cackowski

Sound design: Marek Kamiński

Map animations: Eastory (https://www.youtube.com/c/eastory)Sources:

IWM D 2373, D 2318, B 14299, D 2315, D 2078, D 14318, D 2334

Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe

Bundesarchiv

Wellcome Images no. L0028759

From the Noun Project: london by Pablo Fernández Vallejo, Patient by Miho Suzuki-Robinson, Patient by Binpodo, Doctor by Wilson Joseph, Hospital by Hare Krishna, School by David, Apartment by Victoruler, Bus by Eucalyp

University of Liverpool Faculty of Health & Life SciencesSoundtracks from the Epidemic Sound:

Farrell Wooten – “Blunt Object”

Johannes Bornlof – “Deviation In Time”

Skrya – “First Responders”

Gunnar Johnsen – “Not Safe Yet”

Johannes Bornlof – “The Inspector 4”

Jon Bjork – “For the Many”

Reynard Seidel – “Deflection”

Rannar Sillard – “March Of The Brave 4”

Cobby Costa – “From the Past”

Fabien Tell – “Last Point of Safe Return”

Cobby Costa – “Flight Path”

Andreas Jamsheree – “Guilty Shadows 4”

Jo Wandrini – “Puzzle of Complexity”Archive by Screenocean/Reuters https://www.screenocean.com.

A TimeGhost chronological documentary produced by OnLion Entertainment GmbH.

From the comments:

World War Two

2 days ago (edited)

It might be surprising that the global healthcare crisis of 2020 has an immediate relationship to WW2, but it does. Although, when you look at it, it’s logical — with every crisis humanity learns a little — it was still a little bit of a surprise to us how direct this relationship was when researching and writing this episode. Was it surprising to you too?On the topic of writing, this is the first episode by our new co-writer, Fiona Rachel Fischer, who will now be a regular contributor to the On the Homefront series — please give her a warm welcome.

July 3, 2020

Back to the Future Middle Ages

At Spiked, Dominic Frisby takes us back to a time when today’s progressive temper tantrums would fit in perfectly with accepted behaviours of the age … the Middle Ages:

How much of what went on in the Middle Ages and early-modern periods do we look back on with abhorrence and a certain amount of perplexity? Burning witches at the stake, lynch mobs, self-flagellation – what possessed people to do such things, we wonder.

But take a step back, look about and you see many of these practices are still flourishing today, though they go by different names.

Here are just some of them.

Let’s start with excommunication. Excommunication meant so much more than being banned from taking communion. It involved you being shunned, shamed, spiritually condemned, even banished. Only through some kind of heavy penance – often a very public, lengthy and humiliating contrition – could you and your reputation be redeemed.

Excommunication became a powerful political weapon. It was dished out to enemies of the faith to destroy their legitimacy. Often it was used as a punishment for sins as minor as uttering the wrong opinion.

What are No Platforming and cancel culture if not a modern form of excommunication? Qualified, competent professionals are hounded out of their jobs and publicly shamed just for uttering the wrong opinion, often simply for a misjudged choice of words. Even just the wrong pronouns.

As often as not, their employer wants a quiet life, so he bows to activist pressure and sacks the target of the witch hunt. Cancel culture is excommunication.

Today’s religions, however, are not the many sects of Christianity that once perforated Europe, but climate change, education, the NHS, gay rights, trans rights, the European Union and multiculturalism. Even coronavirus and the lockdown have become sacrosanct.

Intellectuals of the right and left, from Polly Toynbee to Nigel Lawson, have described the NHS as Britain’s religion. It has replaced the Virgin Mary as the divine matriarch. Why this worship? I suggest it goes back to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when the state began to replace the church as the main provider of education, welfare and healthcare. After 1945, it was just a matter of time before the welfare state achieved altar status.

June 14, 2020

Healthcare is a provincial responsibility … thank goodness

Chris Selley reminds us that despite all the attention the media pays to every twitch of the federal government, it’s the provinces that are actually responsible for the healthcare systems in their territory:

Here in Canada, however, astonishing scenes continue. On Thursday the Toronto Transit Commission announced it intends to make masks mandatory for riders — no word of a lie — in three weeks, on July 2. That’s assuming the commission approves the measure … next Wednesday. TTC CEO Rick Leary was at pains to stress the rule would never be enforced.

Meanwhile Theresa Tam, Canada’s chief public health officer, could not appear more reluctant to endorse mask wearing unless she advised against wearing them altogether — which was, famously, her original position. On Wednesday, she unveiled a four-bullet-point plan for getting safely back to semi-normal under the moniker “out smart.” The word “masks” does not appear. Supplementary text only concedes they “can be used … when you can’t maintain physical distance of two metres.”

This is a strange qualification: The official federal advice stresses you shouldn’t touch your mask except to take it off at home and immediately wash your hands. You shouldn’t be taking it on and off while you’re out and about, when social distancing suddenly becomes impossible. But it’s not as strange as the qualification Tam offered on her Twitter account, where she offered a link to an instructional video but only “if it is safe for you to wear a non-medical mask or face covering (not everyone can).”

It is true that some people with asthma or severe allergies have trouble wearing masks. Presumably they know who they are, and would not risk suffocating themselves when mask-wearing isn’t even strongly recommended, let alone mandatory. Blind people will struggle to keep two metres’ distance from others. People with aquagenic urticaria can’t wash their hands with water. People without arms can’t cough into their sleeves. Those “out smart” recommendations aren’t qualified, because that would be silly — as is the qualification on masks.

I would be lying if I said I had any idea what the hell is going on. But this never-ending weirdness is doing us a favour, in a way. The fact is, we have been paying far too much attention to the feds throughout this ordeal. Canada’s COVID-19 experience was always much too different from region to region to justify everyone taking their cues from a single public health agency — let alone one that comprehensively botched something as simple as issuing self-isolation advice to returning foreign travellers.

Canada is a federation by design, not by accident, and thank goodness for that: Far better that most provinces’ authorities did a good job knocking down COVID-19 than that a single one screwed it up for the whole country. It’s something Liberals and New Democrats should bear in mind next time they find themselves demanding yet another “national strategy” in a provincial jurisdiction.

February 19, 2020

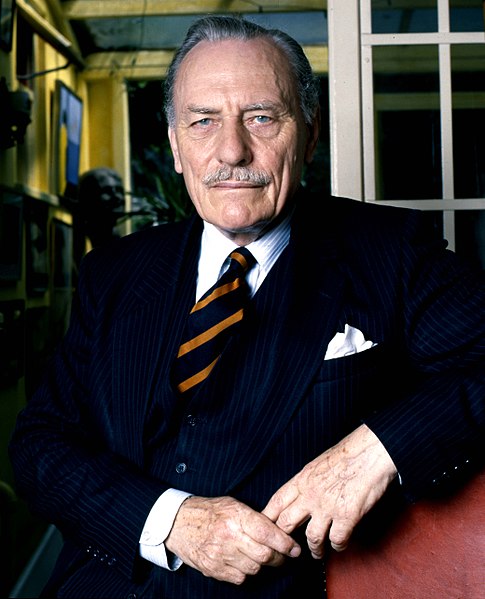

Enoch Powell

Theodore Dalrymple reviews a recent book by Paul Corthorn on Powell’s career and the concerns that animated him:

It does not pretend to be a biography, or even an intellectual biography. Rather, it chronicles, scrupulously but somewhat drily, Powell’s varying attitudes toward the main subjects of his political concerns: international relations, economics, immigration, Britain’s relations with Europe, and the status of Northern Ireland in the United Kingdom. Powell’s wider intellectual interests and religious views are scarcely touched upon, though it is mentioned that he went from being a believer to being (under the influence of Nietzsche) an atheist, to then returning to Christian belief. There is no description of his character in this book, not even by implication, and with this book as a guide, one would not recognise him if one met him. It is not possible to tell whether the author admires or detests his subject. This neutrality creates confidence in the accuracy of his scholarship, but also makes his book less than a pleasurable or exciting read. Perhaps it is the sign of a frivolous mind, but I prefer even histories of ideas to be spiced with a little biography (or, more truthfully, gossip).

The author does, however, offer a unifying interpretation of Powell’s various political concerns, namely that they were all responses to Britain’s precipitous national decline, the steepest part of which occurred in his lifetime, but which is continuing apace to the extent that Britain might even cease to be a nation at all. Powell was born in a great power and died in an enfeebled country with no industrial or military might, with precious little patriotism, and with no sense either of grandeur or collective purpose.

That this decline – relative rather than absolute, except in such fields as the maintenance of law and order — was inevitable given the conjunctures of the age, was evident to Powell (though not at first). This relative decline was already implicit in Disraeli’s dictum that “the Continent [of Europe] will not suffer England to be the workshop of the world.”

Powell’s concerns, then, were how to manage Britain’s decline and how to find it a new place in the world. He had not always been perceptive about the scale of its decline. He clung, for example, to the illusion that the Empire might still count for something even after the Second World War. Thereafter, however, he became a devotee of a kind of Realpolitik, to the extent of wanting a rapprochement or even alliance with the Soviet Union to balance the power of the United States, whose aims he had long distrusted. He discounted ideology, including communism, as a force in international politics, which is odd in a man who was by far the most intellectual and intellectually accomplished of all British politicians of the 20th century, being both a classical scholar and a brilliant linguist. He seemed to think that Soviet ambition was merely that of any large power in the great game. Those countries that fell into its grip knew otherwise.

On economics, Powell was an early devotee of the superiority of the market over state planning at a time when the intellectual tide was running the other way. There was one important subject, however, on which he was a confirmed statist, namely that of health care. He was for a time Minister of Health in the British government, during which he fiercely defended the NHS. He believed that the government had an ethical duty to provide health care for its citizenry, and it never seemed to occur to him that the centralised NHS was not the only possible way of doing so. He was often highly suspicious of international comparison, but it is difficult to see how judgment of the merits of a system could be made without it. It was clear, moreover, that in this, as in other fields, Britain was at best very mediocre. Perhaps Powell was blind to the NHS’s mediocre performance because of the benevolence of its stated intentions (an occupational hazard among intellectuals, even — or perhaps especially — among brilliant ones). At any rate, he never satisfactorily explained why health care should be different from other spheres of service provision in the superiority of private over public organization.

March 23, 2019

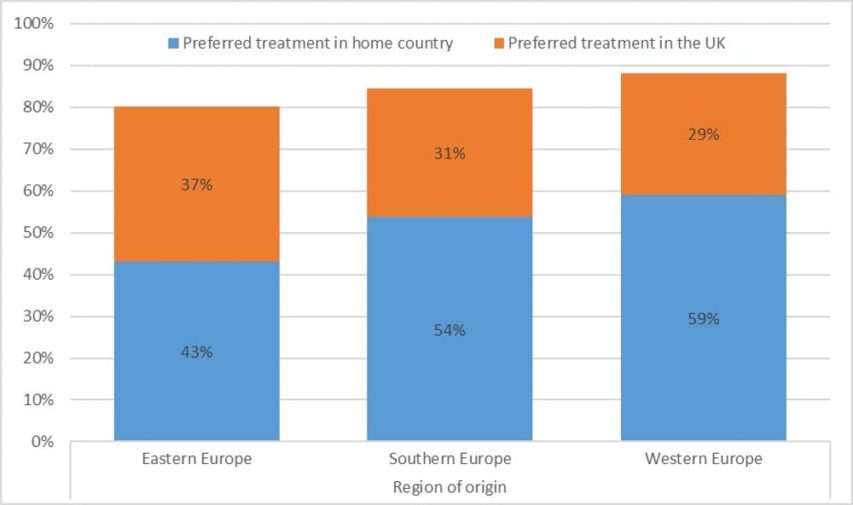

The NHS, Britain’s “national treasure”, gets panned by other EU patients who’ve experienced non-NHS care

In The Conversation, Chris Moreh, Athina Vlachantoni, and Derek McGhee report that — contrary to British myth-making — the National Health Service isn’t the envy of the civilized world:

Britain’s National Health Service is often described as a “national treasure”. And it is a sentiment those on the left and the right of the political divide agree on. The British public are so proud of the NHS, they made it the central theme of the opening ceremony of the 2012 London Olympic Games.

But this pride has also been coupled with fears that the universal healthcare provided by the NHS might be taken advantage of by patients from outside the UK. A few months after the Olympics, the then health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, felt the need to clarify that “we are a national health service, not an international health service”. The 2015 election-winning manifesto of the Conservative party made this point even clearer when it pledged to “tackle health tourism” and “recover up to £500m from migrants who use the NHS”.

But our research shows that while the NHS may be a national treasure to British people, EU migrants would rather be treated in their countries of origin. As a 38-year-old woman from Germany put it: “Sorry, NHS? No thanks.” And the reasons for rejecting the NHS? A 25-year-old man from the Netherlands says it’s because the “NHS is slow and the medical care mediocre”. Or, at least, it “is rather poor compared to healthcare in my country,” says a 45-year-old woman from Germany.

But why should British people worry about what EU migrants think of their health service? What EU migrants think and choose is important because they are familiar with at least two European healthcare systems. They have the information and personal experience that most British citizens do not. There is a lot to be learnt from them.

February 20, 2018

Johan Norberg – Swedish Myths and Realities

ReasonTV

Published on 6 Aug 2008Johan Norberg, author of In Defense of Global Capitalism, sits down with reason.tv’s Michael C. Moynihan to sort out the myths of the Sweden’s welfare state, health services, tax rates, and its status as the “most successful society the world has ever known.”

February 3, 2018

The logical endpoint of socialized medicine

In the Guardian, Nick Cohen explains what Brits will need to do to maintain the National Health Service as their key defining national institution:

If you imagine a healthy future for Britain, or any other country that has put the hunger of millennia behind it, you see a kind of dictatorship. Not a tyranny, but a society that ruthlessly restricts free choice. It is a future that views the mass of people as base creatures jerked around by desires they cannot control. Expert authority must engineer their lives from above for their own good and the common good.

The one who pays the piper calls the tune, and when it’s the government paying the need to keep healthcare costs down will first encourage and later mandate more and more restrictions on the freedoms of the people. Oddly, although he starts out strongly, the rest of the piece falls short of the more stringent restrictions that logic would dictate, concentrating on the relative trivia of expanding pedestrian and bicycle access to downtown areas and corresponding restrictions to private vehicles, plus moving fast food outlets further away from schools.

I can feel the force of the objections. When we imagine a healthier future we are also imagining a more authoritarian state. Individual choice will be constrained and wisdom of the crowd rejected. Women will wonder who will chop the vegetables and cook the dinners when ultra-processed food is taxed to the point of extinction.

Beyond gender lies an undoubted class element in public health campaigns. Sugar and fat addiction, like all addictions, provide a temporary respite for the poor, the depressed and the disappointed. Perhaps we should offer them better lives rather than snatch away the few comforts they enjoy. This sounds a stirring counter-argument. But as any reader who has been an addict will know, addiction prevents you finding a better life. For when you suffer the multiple morbidities of diabetes, arthritis, cancer and strokes, your sicknesses are your life. You do not have the freedom to choose to change it.

God knows, there are good reasons to mistrust experts re-engineering societies from above. But as with tobacco, freedom of choice in the food and car markets has left us with no choice but to trust them.

To safeguard the NHS from bankruptcy, the government will end up looking at quite draconian efforts to reduce or eliminate risks to public health (generously interpreted). First the minor nudges, like raising the prices of alcoholic beverages and tobacco products to discourage smoking and drinking, then perhaps the same for whatever foods are currently considered to be Public Enemy Number One (last year it was fat, this year it’s sugar, next year it might be carbohydrates in general). Then, when the nudges haven’t achieved their intended ends, harsher measures are called for and will need to be implemented over a wider range of products, services and activities, as human beings have an amazing capability to sidestep or avoid what their betters want for them. Exercise will be first encouraged, then demanded, and finally required. Dangerous activities will first be discouraged, then penalized, then finally outlawed.

We’ve already seen the beginnings of the move from mere nudges to more open control, as smokers and the obese are starting to face restrictions on their access to the NHS until they show more than a token obedience to medical authority. Your doctor will slowly morph from mere caregiver to guardian to overseer. All in the name of public health, of course.

H/T to Natalie Solent for the original link.

October 19, 2017

Sir Humphrey Appleby on Education and Health Care

RadioFreeCanada1

Published on 5 May 2010

August 13, 2017

QotD: The measurement problem in government

Now take health insurance. (Or, if you live, like me, in a country with a national healthcare system that has a single comprehensive payer, the health system.) There are periodic suggestions that we should punish bad behaviour, behaviour that increases medical costs: Scotland has an alcoholism problem so we get the Alcohol (Minimum Pricing)(Scotland) Act, 2012. Obesity comes with its own health risks, and where resource scarcity exists (for example, in surgical procedures), some English CCGs are denying patients treatment for some conditions if they are overweight.

It should be argued that these are really stupid strategies, likely to make things worse. Minimum alcohol pricing is regressive and affects the poor far more than the middle-class: it may cause poor alcoholics to turn the same petty criminality observed among drug addicts, to fund their habit. And denying hip replacements to overweight people isn’t exactly going to make it easier for them to exercise and improve their health. But because we can measure the price of alcohol, or plot someone’s height/weight ratio on a BMI chart, these are what will be measured.

It’s the classic syllogism of the state: something must be controlled, we can measure one of its parameters, therefore we will control that parameter (and ignore anything we can’t measure directly).

Charles Stross, “It could be worse”, Charlie’s Diary, 2015-10-09.

April 24, 2017

QotD: Introducing socialized medicine in Europe

There are things left behind, in that past I came from, things I can easily live without. First there’s the lack of access to medical care. Most Europeans who are happy with socialized medicine are happy because at the time it was introduced it was a huge step up over what was available at the beginning of the century — when it was introduced there. If all you have in the way of treatment is a local nurse who administers shots, the local pharmacist which (say, apropos nothing) will change dressings on the back you completely skinned while seaside-cliff climbing (or rather falling from. I managed to turn around and take the slope on my back. I still don’t remember/have no idea how we kept mom from seeing the dressings) and the occasional overworked, over harried doctor who will do house calls at a prohibitive price if you’re seriously ill, yeah. Socialized medicine is an improvement over that. I don’t think the progressives (I almost typed primitives — curse you, auto-correct mind) who push for socialized medicine understand that it’s not an improvement even over the f*cked up bureaucracy of the US. They tend to live in a state of envy of the fact that France has a pony and imagine that pony neither craps nor eats.

Sarah A. Hoyt, “Being a Time Traveler”, According to Hoyt, 2015-07-12.

February 3, 2017

QotD: Obamacare, or something like it, was probably inevitable

Obamacare? Well, here’s the truth of the matter: America is addicted to medical care and demands that it be delivered in infinite quantity, in flawless quality, no matter the cost, as long as no one has to pay anything like full price, directly. Unfortunately, the cost does matter, and even if we were willing to devote infinite resources to medicine, we lack the human quality to provide what’s demanded. Short version: [Obama] had to do something; eventually we were going to bankrupt ourselves in the interests of keeping someone’s great-grandmama alive another day or so. I’m not sure what that something was, mind you, and I am pretty sure that Obamacare wasn’t it. But, be fair; he really had to try to do something. So will Donald Trump, and I don’t mean just repeal Obamacare. You may as well get used to the idea.

Tom Kratman, “Free at last! Free at last!”, EveryJoe, 2017-01-23.

May 13, 2016

British doctors and the attraction of moving to Australia

Scott Alexander talks about the dispute between the junior doctors and the British government:

A lot of American junior doctors are able to bear this [the insane working hours] by reminding themselves that it’s only temporary. The worst part, internship, is only one year; junior doctorness as a whole only lasts three or four. After that you become a full doctor and a free agent – probably still pretty stressed, but at least making a lot of money and enjoying a modicum of control over your life.

In Britain, this consolation is denied most junior doctors. Everyone works for the government, and the government has a strict hierarchy of ranks, only the top of which – “consultant” – has anything like the freedom and salary that most American doctors enjoy. It can take ten to twenty years for junior doctors in Britain to become consultants, and some never do. […]

Faced with all this, many doctors in Britain and Ireland have made the very reasonable decision to get the heck out of Britain and Ireland. The modal career plan among members of my medical school class was to graduate, work the one year in Irish hospitals necessary to get a certain certification that Australian hospitals demanded, then move to Australia. In Ireland, 47.5% of Irish doctors had moved to some other country. The situation in Britain is not quite so bad but rapidly approaching this point. Something like a third of British emergency room doctors have left the country in the past five years, mostly to Australia, citing “toxic environment” and “being asked to endure high stress levels without a break”. Every year, about 2% of British doctors apply for the “certificates of good standing” that allow them to work in a foreign medical system, with junior doctors the most likely to leave. Doctors report back that Australia offers “more cash, fewer hours, and less pressure”. I enjoy a pretty constant stream of Facebook photos of kangaroos and the Sydney Opera House from medical school buddies who are now in Australia and trying to convince their colleagues to follow in their footsteps.

Upon realizing their doctors are moving abroad, British and Irish health systems have leapt into action by…ignoring all systemic problems and importing foreigners from poorer countries who are used to inhumane work environments. I worked in some rural Irish towns where 99% of the population was white yet 80% of the doctors weren’t; if you have a heart attack in Ireland and can’t remember what their local version of 911 is, your best bet is to run into the nearest mosque, where you’ll find all the town’s off-duty medical personnel conveniently gathered together. This seems to be true of Britain as well, with the stats showing that almost 40% of British doctors trained in a foreign country (about half again as high as the US numbers, even though the US is accused of “stealing the world’s doctors” – my subjective impression is that foreign doctors try to come to the US despite barriers because they’re attracted to the prospect of a better life here, but that they are actively recruited to Britain out of desperation). Many of the doctors who did train in Britain are new immigrants who moved to Britain for medical school – for example, the Express finds that only 37% of British doctors are white British (the corresponding number for America is something like 50-65%, even though America is more diverse than Britain). While many new immigrants are great doctors, the overall situation is unfortunate since a lot of them end up underemployed compared to their qualifications in their home country, or trapped in the lower portions of the medical hierarchy by a combination of racism, language difficulties, and just the fact that everyone is trapped in the lower portions of the medical hierarchy these days.

If Britain continues along its current course, they’ll probably be able to find more desperate people willing to staff its medical services after even more homegrown doctors move somewhere else (70% say they’re considering it, although we are warned not to take that claim at face value). I work with several British and Irish doctors in my hospital here in the US Midwest, they’re very talented people, and we could always use more of them. But this still seems like just a crappy way to run a medical system.

I don’t know anything about the latest dispute that has led to this particular strike in Britain. Both sides’ positions sound reasonable when I read about them in the papers. I would be tempted to just split the difference, if not for the fact several years of medical work in the British Isles have taught me that everything that a government health system says is vile horrible lies, and everybody with a title sounding like “Minister of Health” or “Health Secretary” is an Icke-style lizard person whose terminal value is causing as many humans to die of disease as possible. I can’t overstate the importance of this. You read the press releases and they sound sort of reasonable, and then you talk to the doctors involved and they tell you all of the reasons why these policies have destroyed the medical system and these people are ruining their lives and the lives of their patients and how they once shook the Health Secretary’s hand and it was ice-cold and covered in scales. I don’t know how much of this is true. I just think of it as something in the background when the health service comes up to doctors and says “Hey, we have this great new deal we want to offer you!”

January 11, 2016

QotD: “[A]nnual health checks as carried out in Britain are a waste of time”

In the same “Minerva” column, we learn that annual health checks on everyone between the ages of 40 and 75 are likely to be useless, at least as carried out in Britain, except possibly as a mild Keynesian stimulus to the economy. When the records of 130,356 people who had undergone such checks were examined, it was discovered that only about 20 per cent of those at high risk of cardiac disease were prescribed statins and even fewer of those with high blood pressure underwent treatment to lower it.

Since the beneficial effects of treatment with statins are a matter of controversy anyway, as being of value mainly to those who already have ischemic heart disease or have had a stroke, and since the treatment of high blood pressure is only marginally beneficial in the first place, so that the benefit of treating fewer than 20 per cent of those with high blood pressure is likely to be minuscule from the public health point of view, we can safely conclude that annual health checks as carried out in Britain are a waste of time — unless wasting time by occupying it is the whole object of the activity, in which case wasting time is not wasting time but using it gainfully. Gainfully, that is, to the person who wastes his time (the doctor) rather than has his time wasted for him (the patient). His time is well and truly wasted.

Part of the problem is the assumption that doing something must be better than doing nothing. Doctors of the past, because there was so little they could in fact do, employed a technique known as masterly inactivity: they assumed an alert watchfulness, giving the patient the impression, which was false but reassuring, that they would do what had to be done in the event that anything untoward happened. Since most people got better anyway, this seemed to confirm the wisdom of the doctor.

Masterly inactivity, however, is no way to increase your fee for service or gain a reputation for technical mastery. Patients too prefer to think that they are doing something rather than nothing to preserve themselves. That is why some of them are not merely surprised, but aggrieved when illness strikes them: for they have done all that they were supposed to do to remain in good health, from eating broccoli to regular bowel biopsies.

Theodore Dalrymple, “Dubious Cures”, Taki’s Magazine, 2014-11-30.

October 13, 2015

Britain’s National Health Service runs up a “deficit of almost £1 billion in just three months”

In the Telegraph a report on the dire financial straits of Britain’s NHS:

NHS trusts in England have racked up a deficit approaching £1 billion in the first three months of the financial year – the worst financial position “in a generation,” regulators have said.

The figure is more than the £820 million overspend for the entire previous year.

Experts warned of a looming winter crisis.

They said the “staggering” figures would result in widespread cutbacks to services, with lengthening waiting times and increased rationing of care.

The statistics for April to June show an overall deficit of £930m across England’s 241 NHS hospital trusts, with three in four trusts in the red.

The statistics show NHS Foundation Trusts had a deficit of £445 million. Other NHS trusts ended the first quarter of the year £485 million in deficit.

The foundation trust sector is under “massive pressure” and can no longer afford to go on as it is, the financial regulator Monitor said.

Regulators said an “over-reliance” on agency nurses and doctors to plug shortages of staff was fuelling the growing debt, which is forecast to reach a record high.