Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Nov 21, 2023

(more…)

February 24, 2024

Feeding Napoleon – Chicken Marengo

February 10, 2024

Napoleon’s Revenge: Wagram 1809

Epic History TV

Published Jun 21, 2019Six weeks after his bloody repulse at the Battle of Aspern-Essling, Napoleon led his reinforced army back across the Danube. The resulting clash with Archduke Charles’s Austrian army was the biggest and bloodiest battle yet seen in European history, and despite heavy French losses, resulted in a decisive strategic victory for the French Emperor.

(more…)

December 18, 2023

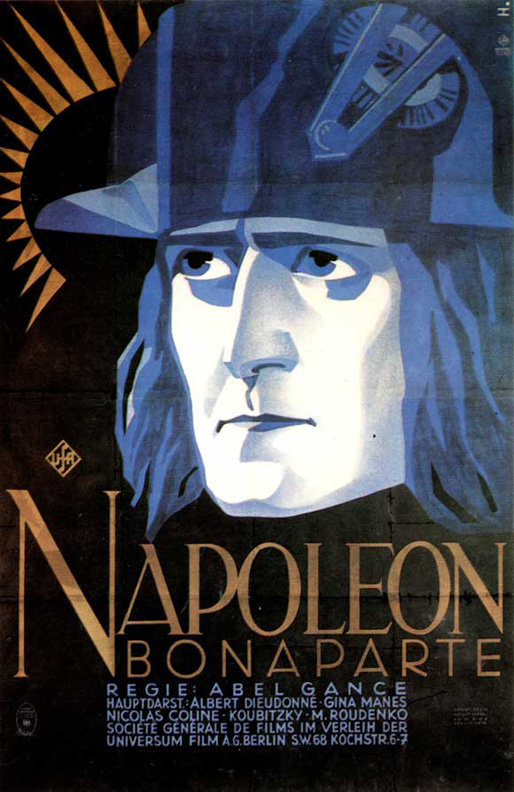

Napoleon Bonaparte on film

In The Critic, Peter Caddick-Adams considers the revival of the biopic, with emphasis on Napoleon Bonaparte, thanks to the recent Ridley Scott movie:

Some of the first motion pictures were biopics, initially silent. In portraying a high-minded individual, historical or contemporary, who has influenced our lives in some way, cinema’s hope is that some of the character’s prestige will rub off into the film. Both sides of the Atlantic have seen countless examples, because the genre is traditionally presented as culturally above a thriller, western or a musical. Its offer is an invitation to see history. Let us take Oppenheimer or Napoleon, with Cillian Murphy and Joachim Phoenix in the title roles. Viewers are attracted by the concept of a true story, be it the designer of the first atomic bomb, or the little emperor who dominated Europe. They may know little or a lot about the subject, even if only hazy knowledge from distant schooldays, but they start with more base knowledge than any other genre.

Gifted directors, in this case Christopher Nolan and Ridley Scott, with their cast hold our hands and walk us into an historical context, hinting at grandeur or importance. We are led into a panorama of life that’s now seen as great or significant. Whether you’re glued to a small screen nightly, or whether you go to the cinema only once or twice a year, the biopic demands attention as “education”, in a way a thriller, horror or romcom flick does not. We are sold the idea that reel history (which can never be real history) somehow merits our valuable time, more than mere “entertainment”.

Napoleon first burst onto the screen in 1927 with a silent-era masterpiece directed by Abel Gance. Far ahead of its time, the final scenes were shot by three parallel cameras, designed to be projected simultaneously onto triple screens, arrayed in a horizontal row called a Triptych, the process labelled “Polyvision” by Gance. It widened the cinematic aspect to a field of vision unknown then or since. The director tried to film the whole in his Polyvision, but found it too technical and expensive. When released, only the centre screen of footage was shown, to a specially composed score. Designed as one episode of several to tell the emperor’s life, which we would today label a franchise, the 1927 extravaganza came in at 5.5 hours, necessitating three intermissions, including one for dinner. Gance had interpreted his biopic as a grand opera. It has been much trimmed and revisited by other directors, including Francis Ford Coppola in the 1980s, and restoration of lost footage is still ongoing. I saw the 5.5-hour version in the Royal Festival Hall in 2000, with a score by Carl Davies (of World at War fame). For a film emerging from the Stone Age of cinematography, its excitingly modern ambition was worth my bum ache. I could see what all the fuss was about.

Curiously, the real value of Gance’s Napoléon was in technique rather than content. If you think of the silent era, it’s mostly the comics who come to mind, playing out their dramas in front of a single static camera. Gance seized this new medium, first embraced in December 1895 by the Parisian Lumière Brothers, and turned it on its head. Napoléon featured not just the Triptych experiment, but many other innovative techniques commonplace today. These included fast cutting between scenes of alternating dialogue, extensive close-ups, a wide variety of hand-held camera shots, location shooting, multiple-camera setups and film tinting (colouring), so altering cinematography for ever.

Although Rod Steiger gave us a different take on Napoleon in Sergei Bondarchuk’s Waterloo of 1970, with its leading actors of the day and massive cast of extras, comprising much of a Soviet army division in period costume and filmed behind the old Iron Curtain, Ridley Scott’s new Napoleon is clearly paying homage to the Gance Napoléon in ambition and length. Scott pretty much picks up the story where Gance left off, and he is able to deploy technology of which Gance could only dream. However, with both films, screenwriter, director and actors are at a disadvantage common to all biopics of having to work against the viewers’ check-list of facts they know, or expect to see included. Thus Scott, like Gance, relies on spectacular technique over storyline. This brings viewers, especially my fellow fuming historians, into a collision between historical truth and the possibilities of celluloid story-making.

Most of us have a mental picture of the character we are invited to watch, which constrains actors and their make-up teams, who have to imitate particular people, with all the wigs, prosthetics and accents that entails. Yet, to view the biopic as a piece of history is to miss the point of the motion picture industry. Pick up a screenplay, and you will be surprised at how few pages it comprises, how few words on each page. None read like a literary biography. With only 90–120 minutes in a typical movie, there is not enough time to cover a character’s full life — not even that of Napoleon in 5.5 hours. Instead, the challenge for the writing-directing team is to extract snippets of a life to demonstrate the evolution of character.

November 25, 2023

Ridley Scott’s Napoleon

I was initially quite interested in Ridley Scott’s Napoleon, but given the criticism from historians, I doubt I’ll make the effort to see the film in the theatre. I’ve quite enjoyed some of Scott’s earlier “historic” movies, but it appears that he’s taken the historical figure of Napoleon and “interpreted” it to better fit his preferences for a film. Bret Devereaux‘s initial response is rather telling:

For this week’s musing, I want to comment at least briefly on dust-up surrounding Ridley Scott’s latest film, Napoleon and historians. As was evidently heavily reported, Ridley Scott responded to historians doing critiques of the film’s historical accuracy by telling them to “get a life” and suggesting that the earliest works on Napoleon were the most accurate and that subsequent historians have just progressively gotten more wrong.

I think there are two questions to untangle here: is the film accurate and does it matter? Now I haven’t yet seen the film, I’ve only seen the trailer. But my response to the trailer seems to have been basically every historian’s response to the trailer: Napoleon shows up at all sorts of places, doing all sorts of things he didn’t do. In particular, the battle scenes I’ve seen in the trailer and other snippets bear functionally no relationship to either Napoleonic warfare in general or the Battle of Austerlitz in particular (the bit with large numbers of soldiers drowning in a frozen lake was disconfirmed at the time; the lake was drained and few remains were found).

All of this is not a huge shock. All of Ridley Scott’s historical movies take huge liberties with their source material. Sometimes that’s in the service of a still interesting meditation on the past (Kingdom of Heaven, The Last Duel), sometimes in service of just a fun movie (Gladiator). Ridley Scott, in particular, has never mastered how basically any historical battle was fought and all of the battle scenes in his movies that I’ve seen are effectively nonsense (including Gladiator, which bears functionally no relationship to how Roman armies actually fought open field battles). Cool looking nonsense, but nonsense. Heck, Gladiator‘s entire plot is basically nonsense with some characters sharing historical names and very little else with their actual historical counterparts (the idea of Marcus Aurelius aiming to restore the republic in 180 is pretty silly).

So it isn’t a surprise that Ridley Scott’s grasp on Napoleonic warfare is about at the level of a not particularly motivated undergraduate student or that he has finessed or altered major historical details to make a better story. Its Ridley Scott, that’s what he does. Sometimes it works great (Kingdom of Heaven), sometimes it works poorly (Exodus: Gods and Kings).

Does it matter?

Unsurprisingly, I think that Ridley Scott is being more than a bit silly with his retorts to historians who are using his film as an opportunity to teach about the past. That’s what we do. Frankly, I find the defensiveness of “get a life” more than a bit surprising, as I assumed Ridley Scott knew he didn’t have much of a grasp on the history and was OK with that (or better yet, did have a grasp on it, but chose to alter it; I do not get this sense from his commentary), but it rather seems like he thinks he does know and is now very upset with the D+ he got on his exam and has decided to blame his “nitpicky” professor instead of his not having done the reading.

That said, when it comes to criticism (in the sense of “saying things are wrong“, rather than in the sense of “critical analysis”), I think there is a distinction to make. In the past I’ve framed this as the degree to which works “make the claim” to some kind of historical validity. It might be a fun exercise to talk about the armor in, say, Dungeons and Dragons or The Elder Scrolls and we might even learn something doing that, but neither of those works is making any claim to historical accuracy or rootedness. And so the tenor of the discussion is quite different.

But here I think Ridley Scott is to a significant degree making the claim. Of the battles, Ridley Scott says, “It’s amazing because you’re actually reconstructing the real thing” and that he “started to think like Napoleon”, which is once again both clearly making that claim (“the real thing”) and also just a remarkable thing to say given how much of a mess his battle scenes generally are. He also comments that “the scale of everything is so massive … I’d have 300 men and a hundred horses and 11 cameras in the field” and while that’s far more cameras than were on any Napoleonic battlefield, that’s just not a statement which suggests that Ridley Scott is even very aware of other achievements in recreating historical battles. Gettysburg (1993) had something on the order of five thousand reenactors on the field for filming and it is by no means the largest such effort! Spartacus (1967) had a cast of eight thousand Spanish soldiers to play the Roman legions.

So while I do not know if Napoleon is a good movie or not – I haven’t seen it yet – it seems pretty clear to me that Ridley Scott did make the claim for some of its fundamental historicity and the response of historians has been to reject that claim. And I think it’s actually quite fair to also skewer the apparent whiny arrogance of Scott making that claim baselessly and then responding petulantly when historians handed him that “D+, please come see me after class”. If you want to make historical fiction, by all means do – Scott is very good at it! – but do not be upset if historians call it what it is.

October 23, 2023

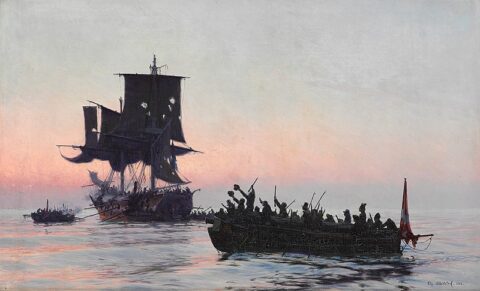

Hero-worship of Admiral Nelson seen as (somewhat) harmful

On Saturday, Sir Humphrey noted the anniversary of Trafalgar and indicated that the Royal Navy’s idolization of Admiral Nelson somewhat obscures the rest of the Royal Navy’s historical role:

“Danish privateers intercepting an enemy vessel during the Napoleonic Wars”.

Oil painting by Christian Mølsted, 1888 from the Collection of the Museum of National History via Wikimedia Commons.

There is an argument, which the author has sympathy with, that the RN has perhaps idolised Nelson too much. That while he did much good, the adoration of him comes at the cost of forgetting countless other leaders and battles which have relevance to this day. This is not to denigrate or play down the impact of Trafalgar, but to ask whether we should be equally aware of other parts of Royal Navy history too. Understanding the Royal Navy of the late 18th and early 19th century can provide us with much to consider and learn from in looking at how to shape the Royal Navy of the early 21st century. If you look at the Royal Navy of today and of Nelson’s time (and throughout the Napoleonic Wars), a strong case can be made that although the technology is materially different, the missions, function, and capability that the RN offers to the Government of the day are little changed.

While we tend to fix attention mostly on the major battle of Trafalgar, the RN fulfilled a wide variety of different missions throughout the war. The fleet was responsible for blockading Europe, monitoring French movements, and providing timely intelligence on the activity of enemy fleets. Legions of smaller ships stood off hostile coasts, outside of engagement range, on lonely picket duties to track the foe. The Royal Navy also maintained forces capable of strategic blockades in locations like Gibraltar and the Skagerrak, relying on chokepoints to secure control of the sea.

The UK was a mercantile nation with a heavy reliance on trade, and with the land routes of Europe closed by Napoleon, the Merchant Navy was vital to victory. The Royal Navy played a key role in escorting ships in convoy, ensuring their protection from hostile forces and helping ensure vitally needed trade goods arrived in British ports. This included timber from colonies in North America, vital to building and repairing warships. Similarly British policy to defeat Napoleon relied on supporting continental land powers, and a steady flow of munitions and materiel were sent by sea, escorted by RN warships to Baltic ports to help support nations fighting France.

The Royal Navy maintained forces of small raiding craft to hold the French coast at risk throughout the wars, sending vessels to attack French coastal locations, capturing intelligence and tying down hundreds of French coastal artillery batteries and thousands of men who could have been deployed elsewhere to protect French soil. More widely the UK engaged in strategic raiding and blockade, for example operations in the Adriatic Campaign (1807-14) where a small number of British warships blockaded ports, conducted amphibious operations and engaged in surface combat with different foes. In the same vein the UK found itself targeted by Danish & Norwegian raiders too, who fought the so-called “Gunboat War” from 1807 to 14 against the UK, where many small scale actions between British brigs and small ships against gunboats in the Baltic. This often forgotten campaign saw violent clashes and victories on both sides with the sinking and capture of many RN vessels to protect convoy trade.

More widely the Royal Navy worked closely with the British Army in a variety of amphibious operations, providing ships to deploy and sustain the Army on campaign. There were a number of impressive amphibious failures, but also some successes too, particularly in the West Indies and Egypt, where working as part of a jointly integrated force, the Royal Navy provided fire support (and even operated Congreve land attack rockets for shore bombardment) as the British Army fought the French ashore. In the Peninsular War the RN was vital for ensuring the supply of Wellington’s forces and, where necessary evacuating them, such as during the retreat from Corunna.

February 21, 2023

Medieval Mardi Gras

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 22 Feb 2022

(more…)

February 11, 2023

Napoleon’s Downfall: Why He Lost the Battle of Nations

Real Time History

Published 10 Feb 2023After the brief summer 1813 cease fire, Napoleon’s campaign in Germany resumes. Surrounded by the Allies — which also manage to slowly turn the tide at Großbeeren, Dennewitz, Kulm, and Dresden — his only remaining option is the ultimate battle which takes place in October 1813 at Leipzig: The Battle of Nations.

(more…)

January 7, 2023

December 19, 2022

Napoleon’s Downfall: German Wars of Liberation 1813

Real Time History

Published 16 Dec 2022After Napoleon’s defeat in Russia in 1812, the situation on the European continent is rapidly shifting. Prussia and Austria are leaving their unhappy alliance with the French. Prussian general Yorck even pledges his support to the Russian Army which is on the move towards Berlin. At Lützen and Bautzen Napoleon still manages to beat the new coalition, but his losses from Russia put him on the backfoot.

(more…)

November 30, 2022

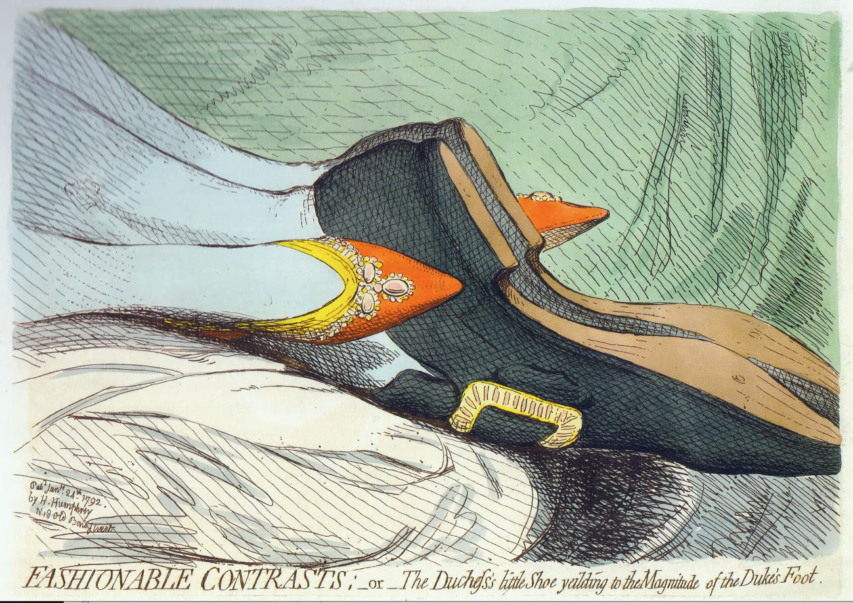

James Gillray

In The Critic, James Stephens Curl reviews a new biography of the cartoonist and satirist James Gillray (1756-1815), who took great delight in skewering the political leaders of the day and pretty much any other target he fancied from before the French Revolution through the Napoleonic wars:

During the 1780s Gillray emerged as a caricaturist, despite the fact that this was regarded as a dangerous activity, rendering an artist more feared than esteemed, and frequently landing practitioners into trouble with the law. Gillray began to excel in invention, parody, satire, fantasy, burlesque, and even occasional forays into pornography. His targets were the great and good, not excepting royalty. But his vision is often dark, his wit frequently cruel and even shockingly bawdy: some of his own contemporaries found his work repellent. He went for politicians: the Whigs Charles James Fox (1749-1806), Edmund Burke (1729-97), and Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (1751-1816) on the one hand, and William Pitt (1759-1806) on the other. Fox was a devious demagogue (“Black Charlie” to Gillray); Burke a bespectacled Jesuit; and Sheridan a red-nosed sot. But Gillray reserved much of his venom for “Pitt the Bottomless”, “an excrescence … a fungus … a toadstool on a dunghill”, and frequently alluded to a lack of masculinity in the statesman, who preferred to company of young men to any intimacies with women, although the caricaturist’s attitude softened to some extent as the wars with the French went on.

As the son of a soldier who had been partly disabled fighting the French, Gillray’s depictions of the excesses of the Revolution were ferocious: one, A Representation of the horrid Barbarities practised upon the Nuns by the Fish-women, on breaking into the Nunneries in France (1792), was intended as a warning to “the FAIR SEX of GREAT BRITAIN” as to what might befall them if the nation succumbed to revolutionary blandishments. The drawing featured many roseate bottoms that had been energetically birched by the fishwives. He also found much to lampoon in his depictions of the Corsican upstart, Napoléon.

[…]

Some of Gillray’s works would pass most people by today, thanks to the much-trumpeted “world-class edication” which is nothing of the sort: one of my own favourites is his FASHIONABLE CONTRASTS;—or—The Duchefs’s little Shoe yeilding to the Magnitude of the Duke’s Foot (1792), which refers to the remarkably small hooves of Princess Frederica Charlotte Ulrica Catherina of Prussia (1767-1820), who married Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1763-1827) in 1791: their supposed marital consummation is suggested by Gillray’s slightly indelicate rendering, in which the Duke’s very large footwear dwarfs the delicate slippers of the Duchess.

“In 1791 and 1792, there was no one who received more attention in the British press than Frederica Charlotte, the oldest daughter of the King of Prussia, whose marriage to the second (and favorite) son of King George and Queen Charlotte, Prince Frederick, the Duke of York set off a media frenzy that can only be compared to that of Princess Diana in our own day.”

Description from james-gillray.org/fashionable.htmlAll that said, this is a fine book, beautifully and pithily written, scholarly, well-observed, and superbly illustrated, much in colour. However, it is a very large tome (290 x 248 mm), and extremely heavy, so can only be read with comfort on a table or lectern. The captions give the bare minimum of information, and it would have been far better to have had extended descriptive captions under each illustration, rather than having to root about in the text, mellifluous though that undoubtedly is.

What is perhaps the most important aspect of the book is to reveal Gillray’s significance as a propagandist in time of war, for the images he produced concerning the excesses of what had occurred in France helped to stiffen national resolve to resist the revolutionaries and defeat them and their successor, Napoléon, whose own model for a new Europe was in itself profoundly revolutionary. What he would have made of the present gang of British politicians must remain agreeable speculation.

September 3, 2022

Napoleon Defeats Russia: Friedland 1807

Epic History TV

Published 28 Sep 2018Napoleon brings his war against Russia and Prussia to an end with victory at Friedland, leading to the famous Tilsit conference, after which Napoleon stood at the peak of his power.

(more…)

July 25, 2022

QotD: Napoleon Bonaparte, the Great Man’s Great Man

The point is, a culture can survive an incompetent elite for quite a while; it can’t survive a self-loathing one. This is because the Great Man theory of History, like everything in history, always comes back around. History is full of men whose society doesn’t acknowledge them as elite, but who know themselves to be such. Napoleon, for instance, and isn’t it odd that as much as both sides, Left and Right, seem to be convinced that some kind of Revolution is coming, you can scour all their writings in vain for one single mention of Bonaparte?

That’s because Napoleon was a Great Man, possibly the Great Man — a singularly talented genius, preternaturally lucky, whose very particular set of skills so perfectly matched the needs of the moment. There’s no “social” explanation for Napoleon, and that’s why nobody mentions him — the French Revolution ends with the Concert of Europe, and in between was mumble mumble something War and Peace. The hour really did call forth the man, in large part, I argue, because the Directory was full of men who were philosophically opposed to the very idea of elitism, and couldn’t bear to face the fact that they themselves were the elite.

Since our elite can’t produce able leaders of itself, it will be replaced by one that can. When our hour comes — and it is coming, far faster than we realize — what kind of man will it call forth?

Severian, “The Man of the Hour”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2019-05-22.

July 17, 2022

QotD: When “the revolution” is in danger, resort to whatever will energize the masses

Fast forward to the French Revolution. They made it clear from the very beginning that this was an ideological going out of business sale — everything must go! The Enlightened believed in nothing but Enlightenment, which meant that even the very notion of “France” had to go — “France” being a benighted relic of the two most un-Enlightened things ever, feudalism and the Catholic Church. That this attitude is just shit-flinging nihilism in pretty Voltairean prose isn’t just the judgment of History; pretty much everyone less insane than Marat and Robespierre saw it right away. Hence the Cult of Reason (soon replaced by the Cult of the Supreme Being) and all the other spiritual-but-not-religious grotesqueries of The Terror.

The problem with that, of course, is that Revolutionary France immediately found herself at war with the rest of Europe. Europe’s crowned heads have rarely been brainiacs, but again, anyone marginally saner than Robespierre saw immediately where the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen was heading. They did the smart thing and invaded, which put the Enlightened in a real bind — war being the third most un-Enlightened thing ever. But they’d rather be hypocrites than dead, the Enlightened, so they had to knock together a new set of national symbols on the fly, ones men would fight and die for (absolutely no one was willing to bleed for “Reason”; whaddaya know).

To their credit, they did a hell of a job. La Marseillaise, Lady Liberty, La patrie en danger! … good stuff. It was part of Napoleon’s singular genius that he could turn these Roman Republic-inspired symbols into first his “consulship”, then his emperorship, but it didn’t have to go that way; Revolutionary France might’ve held out had the Littlest Corporal been killed in action. The important thing here is to note how effective such explicitly nationalist, indeed rabidly jingoist, symbols are, even when pushed by guys who not five minutes ago were proclaiming the Brotherhood of Man.

The Soviets did the same thing, and for the same reasons — look how fast “Workers of the world, unite!” became first the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, then the Great Patriotic War for the Fatherland – but they, too, went through an incredibly fecund period of inventing unifying symbols. Even though History has passed few clearer judgments than she has on Communism, you have to admit that as a symbol, the Soviet hammer-and-sickle is world class.

Severian, “Repost: National Symbols”, Founding Questions, 2021-10-27.

June 20, 2022

Claude Chappe and the Napoleon Telegraph

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 2 Mar 2022The development of technology for speedy long-distance communication dates back to antiquity, and reached its pre-electronic peak in the telegraph before Samuel Morse’s telegraph. Before wires crossed the world, Napoleonic France could send a message from Paris to Lille, a distance of some 250 kilometers, in ten minutes.

Check out our new community for fans and supporters! https://thehistoryguyguild.locals.com/

This is original content based on research by The History Guy. Images in the Public Domain are carefully selected and provide illustration. As very few images of the actual event are available in the Public Domain, images of similar objects and events are used for illustration.

You can purchase the bow tie worn in this episode at The Tie Bar:

https://www.thetiebar.com/?utm_campai…All events are portrayed in historical context and for educational purposes. No images or content are primarily intended to shock and disgust. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Non censuram.

Find The History Guy at:

New community!: https://thehistoryguyguild.locals.com/

Please send suggestions for future episodes: Suggestions@TheHistoryGuy.netThe History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

teespring.com/stores/the-history-guyScript by THG

#history #thehistoryguy #France

June 17, 2022

Napoleon’s Retreat from Moscow – Why He Failed in Russia

Real Time History

Published 16 Jun 2022Sign up for the CuriosityStream + Nebula Bundle: https://curiositystream.com/realtimeh…

Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow and from Russia as a whole is one of the most dramatic scenes in history. Starving and freezing, the French Grande Armée is desperately trying to reach the Berezina River. The revitalized Russian Army is on their heels and almost catches their prey in the 2nd Battle of Krasny. But it wasn’t just “General Winter” that defeated Napoleon in Russia.

» SUPPORT US ON PATREON

https://patreon.com/realtimehistory» THANK YOU TO OUR CO-PRODUCERS

John Ozment, James Darcangelo, Jacob Carter Landt, Thomas Brendan, Kurt Gillies, Scott Deederly, John Belland, Adam Smith, Taylor Allen, Rustem Sharipov, Christoph Wolf, Simen Røste, Marcus Bondura, Ramon Rijkhoek, Theodore Patrick Shannon, Philip Schoffman, Avi Woolf, Emile Bouffard, William Kincade, Daniel L Garza, Stefan Weiß, Matt Barnes, Chris Daley, Marco Kuhnert, Simdoom» SOURCES

Boudon, Jacques-Olivier. Napoléon et la campagne de Russie en 1812 (2021).

Chandler, David. The Campaigns of Napoleon, Volume 1 (New York 1966).

Lieven, Dominic. Russia Against Napoleon (2010).

Mikaberidze A. The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape (Pen&Sword Military, 2010)

Rey, Marie-Pierre. L’effroyable tragédie: une nouvelle histoire de la campagne de Russie. (2012).

Zamoyski, Adam. 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March on Moscow. (2005).

Отечественная война 1812 года. Энциклопедия (Москва: РОССПЭН, 2004)

Безотосный В. М. Россия в наполеоновских войнах 1805–1815 гг. (Москва: Политическая энциклопедия, 2014)

Троицкий Н.А. 1812. Великий год России (Москва: Омега, 2007)

(Прибавление к «Санкт-Петербургским ведомостям» №87 от 29 октября 1812 / http://www.museum.ru/museum/1812/War/…)» OUR STORE

Website: https://realtimehistory.net»CREDITS

Presented by: Jesse Alexander

Written by: Jesse Alexander

Director: Toni Steller & Florian Wittig

Director of Photography: Toni Steller

Sound: Above Zero

Editing: Toni Steller

Motion Design: Toni Steller

Mixing, Mastering & Sound Design: http://above-zero.com

Digital Maps: Canadian Research and Mapping Association (CRMA)

Research by: Jesse Alexander, Sofia Shirogorova

Fact checking: Florian WittigChannel Design: Simon Buckmaster

Contains licensed material by getty images

Maps: MapTiler/OpenStreetMap Contributors & GEOlayers3

All rights reserved – Real Time History GmbH 2022