Tim Worstall explains why the headline-friendly numbers in a recent ILO report are nothing to be surprised at:

“Nearly half of all global pay is scooped up by only 10% of workers, according to the International Labour Organization, while the lowest-paid 50% receive only 6.4%.

“The lowest-paid 20% – about 650 million workers – get less than 1% of total pay, a figure that has barely moved in 13 years, ILO analysis found. It used labour income figures from 189 countries between 2004 and 2017, the latest available data.

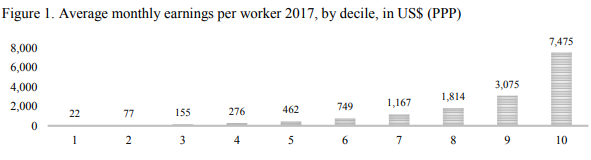

“A worker in the top 10% receives $7,445 a month (£5,866), while a worker in the bottom 10% gets only $22. The average pay of the bottom half of the world’s workers is $198 a month.”

[…]

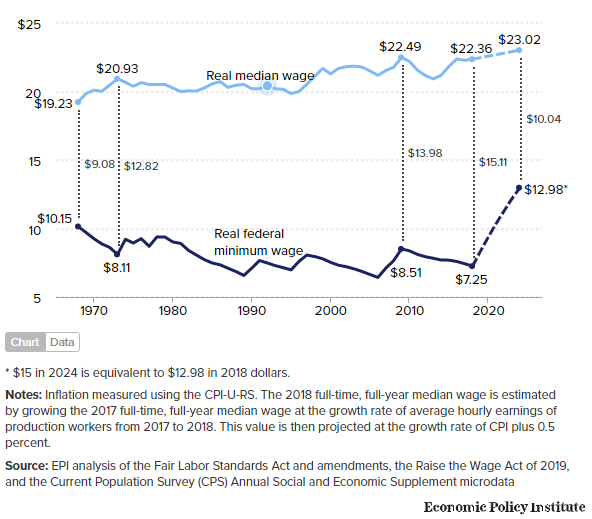

The explanation? To be in the top 10% of the global pay distribution you need to be making around and about minimum wage in one of the rich countries. Via another calculation route, perhaps median income in those rich countries. No, that £5,800 is the average of all the top 10%.

Note that this is in USD. About £2,000 a month puts you in the second decile, that’s about UK median income of 24,000 a year.

And as it happens about 20% of the people around the world are in one of the already rich countries. So, above median in a rich country and we’re there. Our definition of rich here not quite extending as far as all of the OECD countries even. Western Europe – plus offshoots like Oz and NZ, North America, Japan, S. Korea and, well, there’s not much else. Sure, it’s not exactly 10% of the people there but it’s not hugely off either.

So, what is it that these places have in common? They’ve been largely free market, largely capitalist, economies for more than a few decades. The most recent arrival, S. Korea, only just managing that few decades. It is also true that nowhere that hasn’t been such is in that listing. It’s even true that nowhere that is such hasn’t made it – not that we’d go to the wall for that last insistence although it’s difficult to think of places that breach that condition.