In the Continental Telegraph, Tim Worstall explains that the US tax system is already drawing too much in tax and any hope of increasing the total revenue will hinge on reducing the tax rate:

“washdc040208-02” by carencey is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

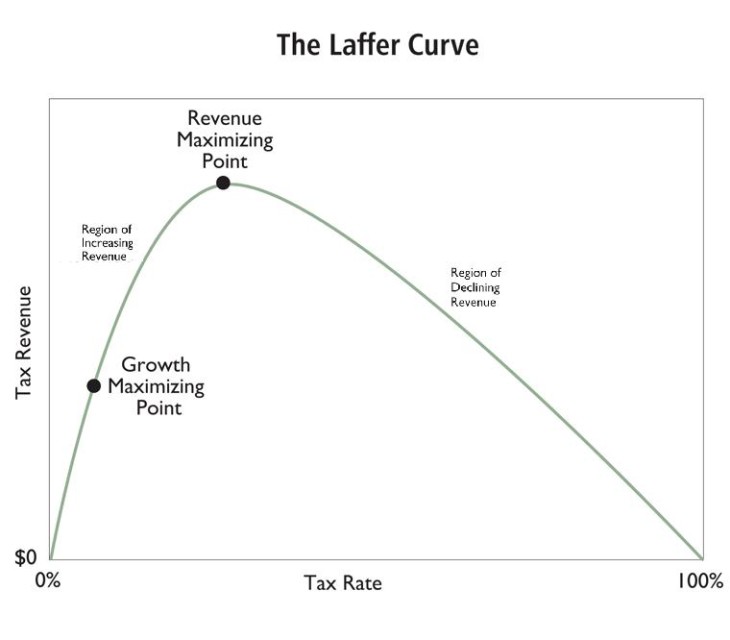

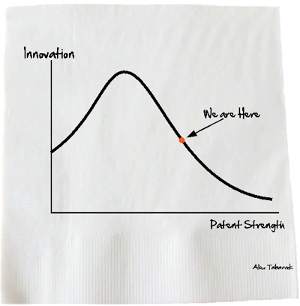

It is often stated that the rate [the Laffer Curve peak rate] discovered here is 75 to 80%. This is not so – that could be the rate if only we entirely and wholly changed the taxation system in a mass of highly undesirable ways. If we remain with roughly what we’ve got in structure and intent then the peak of the Laffer Curve is 54%. That is not income tax, that is taxes upon income. That means we add together all Federal and State taxes upon income, including “employer paid” portions of Social Security, Medicaid, special amounts for this and that and so on and on. Anyone even vaguely familiar with the US taxation system will note that top earners are, already in many states, paying this or more.

There is something else though. The Laffer Curve is not about taxes upon high earners. It is about taxes upon income. It’s true that there will be slight differences in what the peak rate on lower incomes should be, or what the peak of the curve is there. The income effect will be higher than the substitution at lower incomes than it is at higher. We don’t know how much so let’s just stick with what we’ve got – 54%.

At which point:

The U.S. has a plethora of federal and state tax and benefit programs, each with its own work incentives and disincentives. This paper uses the Fiscal Analyzer (TFA) to assess how these policies, in unison, impact work incentives. TFA is a life-cycle, consumption-smoothing program that incorporates household borrowing constraints and all major federal and state fiscal policies. We use TFA in conjunction with the 2016 Federal Reserve Survey of Consumer Finances to calculate Americans’ remaining lifetime marginal net tax rates. Our findings are striking. One in four low-wage workers face marginal net tax rates above 70 percent, effectively locking them into poverty.

This includes the withdrawal of welfare benefits as income rises – as it should – and so is compatible with the Universal Credit idea that the peak tax and withdrawal rate should be 60%. Or is it 66%?

As we can see that rate is hugely above the Laffer Curve peak. It should, therefore, be lower.

It’s possible to extend the taper. Withdraw benefits at slower rates as income rises. This is, however, hugely, vastlylily, expensive. So it’s not going to happen to any significant degree and if it does then it will be financed by reducing the overall amount of benefit being paid. Which would mean taking money off the truly low income in order to soften the blow to the marginally low income – not the way we want to be doing things.

The only other way to do this is to reduce the taxation of the income of those low income folks. This has been done, a bit, by the Trump tax reforms and the much larger personal deduction. A further bite could be taken by FICA taxation only applying to the income above the personal deduction, not from dollar $1 of income as now. In fact that would be the simplest manner of at least beginning to get to grips with this problem. FICA only starts at $12,000 a year or so. Or even, if all are to be sensible, starting income tax and FICA only at the poverty line, currently $14,000 or so a year for a single adult.