Ontario Regiment Museum

Published Jan 26, 2022This multi-part series was originally created in support of our friends at D-Day Conneaut for presentation during their live stream in 2020.

In part 5 the Museum’s Operation Manager Dan Acre details the history of a Canadian-made WWII vehicle, the Universal Carrier. (Please forgive the sound quality, it was one of the first videos we produced in the early stages of the pandemic.)

(more…)

March 25, 2024

WWII Allied Vehicles – Universal Carrier

March 9, 2024

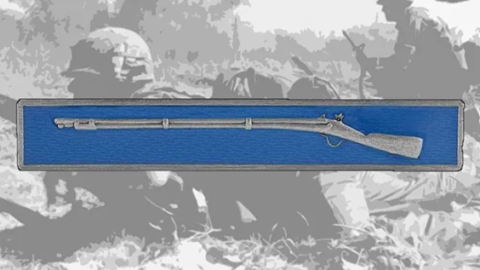

1871 Spencer Rifle Conversion

Forgotten Weapons

Published Nov 12, 2014The Spencer repeating rifle was a major leap forward in infantry firepower, and more than one hundred thousand of them were purchased by the US military during the Civil War. The Spencer offered a 7-round magazine of rimfire .56 caliber cartridges in an era when the single-shot muzzle-loading rifle was still predominant. This particular Spencer is a long rifle which was one of roughly 1100 rebuilt from damaged carbines in 1871 at Springfield Arsenal.

(more…)

March 2, 2024

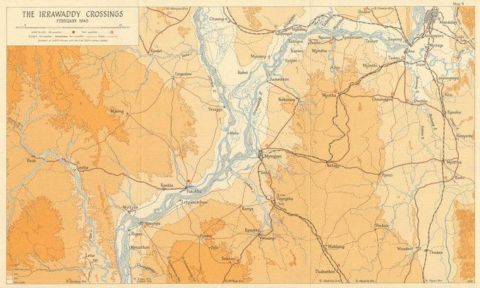

Crossing the Irrawaddy

Dr. Robert Lyman is on a visit to the site of a very significant event in the battle for Burma in 1945:

On 13-14 February 1945, 79-years ago this month the 7th Indian Division commanded by Major General Geoffrey Evans secured crossings over the Irrawaddy at Pakkoku and Nyaung-U/Bagan. The northern crossing (Pakkoku) was designed to allow Punch Cowan’s 17th Indian Division, and the Sherman tanks of 255 Indian Tank Brigade, to race across country to seize Meiktila. The southern ones, at Nyaung-U and Bagan (a few miles to the south still), were designed to prevent the enemy from interfering with the operations against Meiktila, and to make him believe that securing the Irrawaddy as a route to Rangoon — and not Meiktila — was Slim’s primary objective. In 2005, for the 60th anniversary of the Irrawaddy crossings, I was privileged to walk the battlefield with three veterans of these crossings, John Chiles (Probyn’s Horse), Manny Curtis (South Lancashire Regiment) and Bert Wilkins (RA, in support of the South Lancs). During that trip we travelled along the Irrawaddy from Bagan, anxiously scouring the maps in the South Lancs’ War Diary searching for B4 beach, where on the early morning of 14 February 1945 two hundred men of 2nd Battalion South Lancashire Regiment had rowed silently across the river to form the vanguard of the 7th Indian Division beachhead. I remember vividly the excitement as we found B4 — it was much easier than I had thought — disembarked from the boat and climbed to the top of the cliffs to find old trenches from the battle. It was an emotional event for the veterans as they recalled the battle and found trenches left by the defenders decades before.

At Nyaung-U the first wave of a company of the 2nd Bn South Lancs (including Manny Curtis) managed to seize the high ground above B4 in the early morning of 14 February. It was the longest opposed river crossing in any theatre of the Second World War. The beaches had been recced by a Sea Reconnaissance Unit and a Special Boat Section. However, subsequent waves of troops from the remainder of the South Lancs, the 4th Battalion 14th Punjab Regiment and the 4th Battalion 1st Gurkha Rifles were mauled by enemy machine gun fire as the leaky canvas boats and temperamental outboard motors failed to cope with the distance they had to cover and the strength of the river’s flow. The enemy? Pagan and Nyaungu were defended not by the Japanese but by three battalions of the Indian National Army’s 4th Guerrilla Regiment, some 2,000 men in well-sited positions overlooking the Irrawaddy. This was the only major engagement of the war when troops of the Indian Army fought in direct combat against the INA. To subdue the enemy positions causing casualties on the water, Sherman tanks of the Gordon Highlanders sniped the enemy positions, and an artillery bombardment by 25-pdrs and a Hurribomber strike pummelled the east bank of the river. Together these actions succeeded in forcing the INA to surrender. Further to the west, at Pagan, the INA’s 9th Battalion took a heavy toll of the assaulting 1/11th Sikh Regiment, before they withdrew to Mount Popa to the rear. River crossing are dangerous, especially for troops with little training in boatmanship, across one of the world’s greatest rivers. But this time the 7th Indian Division succeeded with little training or preparation. By the end of the day the east bank was in its hands. Amazingly, a cinematographic unit were available to film some of the crossings at Nyaung-U. An 8-minute reel of the landings can be seen in the IWM on JFU35.

Today I was able to revisit B4. Not much had changed in nearly 20-years. The size of the Irrawaddy even in the dry season is astonishing, the task given to the men of 33 Brigade enormous. In 2005 we climbed the cliffs that Manny and his friends had raced up in 1945. Looking at them again today, I realised just how Gallipoli-like was the terrain. In the hands of of better trained enemy, 33 Brigade should never have managed to get off the beachhead. Rippling rows of gullies flow behind the initial landing site: if these had all been defended, a position of great depth and near impregnability could have been achieved. These photos look down on B4 and across to the position up which the men of 2nd South Lancs scrambled.

December 28, 2023

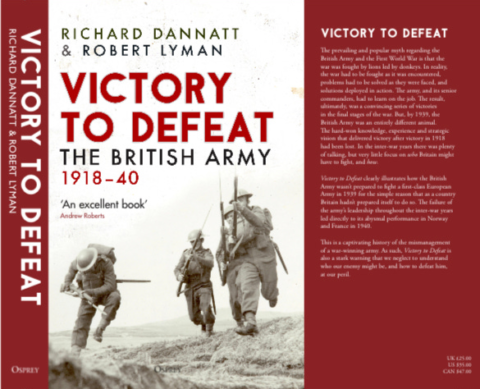

War-winning expertise of 1918, completely forgotten by 1939

Dr. Robert Lyman writes about the shocking contrasts between the British Army (including the Canadian and Australian Corps) during the Hundred Days campaign of 1918 and the British Expeditionary Force that was driven from the continent at Dunkirk:

There was a fleeting moment during the One Hundred Days battles that ended the First World War in France in which successful all-arms manoeuvre by the British and Commonwealth armies, able to overturn the deadlock of previous years of trench stalemate, was glimpsed. But the moment, for the British Army at least, was not understood for what it was. With hindsight we can see that it was the birth of modern warfare, in which armour, infantry, artillery and air power are welded together able successfully to fight and win a campaign against a similarly-equipped enemy. Unfortunately in the intervening two decades the British Army simply forgot how to fight a peer adversary in intensive combat. It did not recognise 1918 for what it was; a defining moment in the development of warfare that needed capturing and translating into a doctrine on which the future of the British Army could be built. The tragedy of the inter-war years therefore was that much of what had been learned at such high cost in blood and treasure between 1914 and 1918 was simply forgotten. It provides a warning for our modern Army that once it goes, the ability to fight intensively at campaign level is incredibly hard to recover. The book that General Lord Dannatt and I have written traces the catastrophic loss of fighting knowledge after the end of the war, and explains the reasons for it. Knowledge so expensively learned vanished very quickly as the Army quickly adjusted back to its pre-war raison d’etre: imperial policing. Unsurprisingly, it was what many military men wanted: a return to the certainties of 1914. It was certainly what the government wanted: no more wartime extravagance of taxpayer’s scarce resources. The Great War was seen by nearly everyone to be a never-to-be-repeated aberration.

The British and Commonwealth armies were dramatically successful in 1918 and defeated the German Armies on the battlefield. Far from the “stab in the back” myth assiduously by the Nazis and others, the Allies fatally stabbed the German Army in the chest in 1918. The memoirs of those who experienced action are helpful in demonstrating just how far the British and Commonwealth armies had moved since the black days of 1 July 1916. The 27-year old Second Lieutenant Duff Cooper, of the 3rd Battalion The Grenadier Guards, waited with the men of 10 platoon at Saulty on the Somme for the opening phase of the advance to the much-vaunted Hindenburg Line. His diaries show that his experience was as far distant from those of the Somme in 1916 as night is from day. There is no sense in Cooper’s diaries that either he or his men felt anything but equal to the task. They were expecting a hard fight, but not a slaughter. Why? Because they had confidence in the training, their tactics of forward infiltration, their platoon weapons and a palpable sense that the army was operating as one. They were confident that their enemy could be beaten.

[…]

It would take the next war for dynamic warfare to be fully developed. It would be mastered in the first place by the losers in 1918 – the German Army. The moment the war ended the ideas and approaches that had been developed at great expense were discarded as irrelevant to the peace. They weren’t written down to be used as the basis for training the post-war army. Flanders was seen as a horrific aberration in the history of warfare, which no-right thinking individual would ever attempt to repeat. Combined with a sudden raft of new operational commitments – in the remnants of the Ottoman Empire, Russia and Ireland – the British Army quickly reverted to its pre-1914 role as imperial policemen. No attempt was made to capture the lessons of the First World War until 1932 and where warfighting was considered it tended to be about the role of the tank on the future battlefield. This debate took place in the public arena by advocates writing newspaper articles to advance their arguments. These ideas were half-heartedly taken up by the Army in the later half of the 1920s but quietly dropped in the early 1930s. The debates about the tank and the nature of future war were bizarrely not regarded as existential to the Army and they were left to die away on the periphery of military life.

The 1920s and 1903s were a low point in national considerations about the purpose of the British Army. The British Army quickly forgot what it had so painfully learnt and it was this, more than anything else, that led to a failure to appreciate what the Wehrmacht was doing in France in 1940 and North Africa in 1941-42.

December 21, 2023

The Battle of Ortona

Army University Press

Published 20 Dec 2023Between 20 and 28 December 1943, the idyllic Adriatic resort town of Ortona, Italy was the scene of some of the most intense urban combat in the Mediterranean Theater. Soldiers of the First Canadian Infantry Division fought German Falschirmjager for control of the city, the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line. The Army University Films Team is proud to present, The Battle of Ortona, as told by Major Jayson Geroux of the Canadian Armed Forces.

December 18, 2023

Battle Taxis | Evolution of the Armoured Personnel Carrier

The Tank Museum

Published 8 Sept 2023Tanks and infantry need to operate together. Tanks provide firepower and protection, the infantry support and protect the tanks. In this video, we look at that vital component of the equation, the Armoured Personnel Carrier and its transition into the modern Infantry Fighting Vehicle.

(more…)

November 30, 2023

Men and Morale: Canadian Army Training in the Second World War

WW2TV

Published 1 Feb 2023Men and Morale: Canadian Army Training in the Second World War

Part of Canadian Week on WW2TV With Megan HamiltonThe Canadian Army of the Second World War spent more time preparing and training their citizen soldiers then they did in sustained action. This chiefly took place across Canada and in the United Kingdom. Adequate training functioned as a cradle for collective action, morale, empowerment, self-confidence, and, ultimately, success in battle. Yet, due to a number of factors, a sufficient standard of training was not always achieved by all.

There were limits to the Canadian Army’s ability to control the morale of its men as it created a vast organization from scratch. Training camp experiences varied, influenced by factors such as food, weather, comfort, group cohesion, leadership, skill level, discipline, social activities, and interactions with local civilians. In fact, it required a constant negotiation between camp leadership and the rank and file. Drawing from her research on both the Canadian and wider Commonwealth armies, Megan’s presentation will explain why soldiers’ morale in training was a difficult, yet vital, balancing act.

Originally from Vernon, British Columbia, Megan Hamilton is a social and military historian of the 20th century. She has an Honours Bachelor of Arts degree from Wilfrid Laurier University and a Master of Arts degree from the University of Waterloo. Her federally-funded master’s research focused on the Canadian experience of the Second World War, specifically the Vernon Military Camp. Megan’s work has been published by a number of platforms and in 2022 she won the Tri-University History Program’s top essay prize for master’s students.

She is currently located in London, England, where she has begun a fully-funded PhD at King’s College London and the Imperial War Museum, supervised by Dr. Jonathan Fennell. Her dissertation is a study of Second World War army training across the Commonwealth.

(more…)

November 28, 2023

QotD: The tactical problem of attacking WW1 trenches

The trench stalemate is the result of a fairly complicated interaction of weapons which created a novel tactical problem. The key technologies are machine guns, barbed wire and artillery (though as we’ll see, artillery almost ought to be listed here multiple times: the problems are artillery, machine guns, trenches, artillery, barbed wire, artillery, and artillery), but their interaction is not quite straight-forward. The best way to understand the problem is to walk through an idealized, “platonic form” of an attack over no man’s land and the problems it presents.

[…]

So, the first problem: artillery. Neither side starts the war in trenches. Rather the war starts with large armies, consisting mostly of infantry with rifles, backed up by smaller amounts of cavalry for scouting duties (who typically fight dismounted because this is 1914, not 1814) and substantial amounts of artillery, mostly smaller caliber direct-fire1 guns, maneuvering in the open, trying to do fancy things like flanking and enveloping attacks to win by movement rather than by brute attrition (though it is worth noting that this war of maneuver is also the period of the highest casualties on a per-day basis). The tremendous lethality of those weapons – both rifles that are accurate for hundreds of yards, machine guns that can deny entire areas of the battlefield to infantry and the artillery, which is utterly murderous against any infantry it can see and by far the most lethal part of the equation – all of that demands trenches. Trenches shield the infantry from all of that firepower. So you end up with parallel trenches, typically a few hundred yards apart as the armies settle in to defenses and maneuver breaks down (because the armies are large enough to occupy the entire front from the Alps to the Sea).

The new problem this creates, from the perspective of the defender, is how to defend these trenches. If enemies actually get close to them, they are very vulnerable because the soldier at the top of the trench has a huge advantage against enemies in the trench: he can fire down more easily, can throw grenades down very easily and also has an enormous mechanical advantage if the fight comes to bayonets and trench-knives, which it might. If you end up fighting at the lip of your trench against massed enemy infantry, you have almost certainly already lost. The defensive solution here, of course, are those machine guns which can deploy enough fire to prohibit enemies moving over no man’s land: put a bunch of those in strong-points in your trench line and you can prevent enemy infantry from reaching you.

Now the attacker has the problem: how to prevent the machine guns from making approach impossible. The popular conception here is that WWI generals didn’t “figure out” machine guns for a long time; that’s not quite true. By the end of 1914, most everyone seems to have recognized that attacking into machine guns without some way of shutting them down was futile. But generals who had done their studies already had the ready solution: the way to beat infantry defenses was with artillery and had been for centuries. Light, smaller, direct-fire guns wouldn’t work2 but heavy, indirect-fire howitzers could! Now landing a shell directly in a trench was hard and trenches were already being zig-zagged to prevent shell fragments flying down the whole line anyway, so actually annihilating the defenses wasn’t quite in the cards (though heavy shells designed to penetrate the ground with large high-explosive payloads could heave a hundred meters of trench along with all of their inhabitants up into the air at a stretch with predictably fatal results). But anyone fool enough to be standing out during a barrage would be killed, so your artillery could force enemy gunners to hide in deep dugouts designed to resist artillery. Machine gunners hiding in deep dugouts can’t fire their machine guns at your approaching infantry.

And now we have the “race to the parapet”. The attacker opens with a barrage, which has two purposes: silence enemy artillery (which could utterly ruin the attack if it isn’t knocked out) and second to disable the machine guns: knock out some directly, force the crews of the rest to flee underground. But attacking infantry can’t occupy a position its own artillery is shelling, so there is some gap between when the shells stop and when the attack arrives. In that gap, the defender is going to rush to set up their machine guns while the attacker rushes to get to the lip of the trench:first one to get into position is going to inflict a terrible slaughter on the other.

Now the defender begins to look for ways to slant the race to his advantage. One option is better dugouts and indeed there is fairly rapid development in sophistication here, with artillery-resistant shelters dug many meters underground, often reinforced with lots of concrete. Artillery which could have torn apart the long-prepared expensive fortresses of a few decades earlier struggle to actually kill all of the infantry in such positions (though they can bury them alive and men hiding in a dugout are, of course, not at the parapet ready to fire). The other option was to slow the enemy advance and here came barbed wire. One misconception to clear up here: the barbed wire here is not like you would see on a fence (like an animal pen, or as an anti-climb device at the top of a chain link fence), it is not a single wire or a set of parallel wires. Rather it is set out in giant coils, like massive hay-bales of barbed wire, or else strung in large numbers of interwoven strands held up with wooden or metal posts. And there isn’t merely one line of it, but multiple lines deep. If the attacker goes in with no preparation, the result will be sadly predictable even without machine guns: troops will get stuck at the wire (or worse yet, on the wire) and then get shot to pieces. But even if troops have wire-cutters, cutting the wire and clearing passages through it will still slow them down … and this is a race.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part I: The Trench Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-17.

1. Direct fire here means the guns fire on a low trajectory; you are more or less pointing them where you want the shell to go and shooting straight at it, as you might with a traditional firearm.

2. The problem with direct-fire artillery here is that you cannot effectively hide it in a trench (because it’s direct fire) and you can’t keep it well concealed, so in the event of an attack, the enemy is likely to begin by using their artillery to disable your artillery. The limitations of direct-fire guns hit the French particularly hard once the trench stalemate set in, because it reduced the usefulness of their very effective 75mm field gun (the famed “French 75” after which the modern cocktail is named [Forgotten Weapons did a video covering both]). That didn’t make direct-fire guns useless, but it put a lot more importance on much heavier indirect-fire artillery.

November 16, 2023

QotD: Infantry soldiers in the age of pike and shot

The pike and the musket shifted the center of warfare away from aristocrats on horses towards aristocrats commanding large bodies of non-aristocratic infantry. But, as comes out quite clearly in their writing, those aristocrats were quite confident that the up-jumped peasants in their infantry lacked any in-born courage at all. Instead, they assumed (in their prejudice) that such soldiers would require relentless synchronized drilling in order to render the complex sequence of actions to reload a musket absolutely mechanical. As Lee points out [in Waging War], this training approach wasn’t necessary – other contemporary societies adapted to gunpowder just fine without it – but was a product of the values and prejudices of the European aristocracy of the 1500 and 1600s.

Such soldiers were, in their ideal, to quickly but mechanically reload their weapons, respond to orders and shift formation more or less oblivious to the battle around them. Indeed, uniforms for these soldiers came to favor high, starched collars precisely to limit their field of vision. This is not the man who, in Tyrtaeus’ words (elsewhere in his corpus), “bites on his lip and stands against the foe” but rather a human who, in the perfect form, was so mechanical in motions and habits that their courage or lack thereof, their awareness of the battlefield or lack thereof, didn’t matter at all. But at least, the [Classical] Greek might think, at least such men still ought not quail under fire but instead stood tall in the face of it.

After all, as late as the Second World War, it was thought that good British officers ought not duck or take cover under fire, in order to demonstrate and model good coolness under fire for their soldiers. The impression I get from talking to recent combat veterans (admittedly, American ones rather than British, since I live in the United States) is that an officer who behaved in that same way on today’s battlefield would be thought reckless (or stupid), not brave. Instead, the modern image of courage under fire is the soldier moving fast, staying low, moving to and through cover whenever possible – recklessness is discouraged precisely because it might put a comrade in danger.

Instead, the courage that is valued in many of today’s armies is the courage to stay calm and make cool, rational decisions. It is, to borrow the first line in Rudyard Kipling’s “If-“, “If you can keep your head when all about you/Are losing theirs and blaming it on you.” Which is not at all what was expected of the 17th century infantryman, whose officers trusted him to make nearly no decisions at all! But, as we’ve discussed, the modern system of combat demands that lots of decisions be devolved down further and further in the command hierarchy, with senior officers giving subordinates (often down to NCOs) the freedom to alter plans on the fly at the local level so long as they are following the general mission instructions (a system often referred to by its German term, auftragstaktik).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Universal Warrior, Part IIa: The Many Faces of Battle”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-02-05.

November 6, 2023

The Army Door Knocker | Pak 35/36 | Anti-Tank Chats

The Tank Museum

Published 14 Jul 2023In this video, we look at the Pak 35/36, the German Army’s first anti-tank gun. Obsolete by 1941, it picked up the nickname Heeresanklopfgerat – the army door knocker – after its inability to penetrate tank armour. In spite of this, it carried on in service until 1945. Chris Copson talks you through the gun and its history.

(more…)

November 5, 2023

Military “institutional racism” and the Expert Infantry Badge

Chris Bray on a recent article in which a USAF Colonel lectures other “white colonels” about institutional racism in America’s military services:

Thoughts about the Air Force colonel who delivers sanctimonious lectures about institutional racism to his fellow “white colonels”.

In you’re an infantry soldier in the US Army, you can distinguish yourself by earning an Expert Infantry Badge. To do that, you have to qualify as an expert with the rifle, then complete a series of skills tests like “set headspace and timing on a caliber .50 machine gun” and “operate as a station in a radio net with SINCGARS radio single channel”. Then, finally, you have to complete a 12-mile road march. You can read the standards for that event here: carry a rifle and magazines, wear a helmet at all times, carry a rucksack weighing at least 35 pounds, and so on. When the person with the stopwatch says that three hours have elapsed, you’re either standing behind the finish line or in front of it; you either earn the EIB or you don’t.

The test isn’t subjective — the judges don’t award you style points. If you crawl across the finish line in a pool of blood and urine, sobbing for mommy, but you do it in less than three hours, and you still have your rucksack and your rifle and everything else at the end, you get the EIB.

Nor is it weighted. If you’re a fourth-generation VMI graduate with a fine old family name that can be found on the rolls of the Mayflower Society, you get the EIB if you cross the finish line on time. If you’re an E-2 who grew up in a trailer park and barely made it out of high school and doesn’t remember the names of all your so-called stepdads, you get the EIB if you cross the finish line on time. Officers and enlisted work to exactly the same standard. The credential comes from the task, full stop. This fact is the core of every credential you can earn in the military: If you’re authorized to wear the Parachutist Badge, you went to Fort Benning, or whatever they call it now, and jumped out of the plane five times without missing the ground. You did the thing. Doing the thing is who you are, in a growing list of things.

As a set of organizations built on task competence, for plainly measurable tasks that can’t be faked or fudged, the armed forces have been America’s first meritocracy. The first black West Point graduate was commissioned in 1877; the first black Medal of Honor recipient was born into slavery. Even in the segregated military, credentials obtained through task competence bore weight, as the court-martial of Jackie Robinson suggests with its outcome: In 1944, in Texas, a black officer was correct to harshly demand respect from a white enlisted soldier.

If you’ve served in the military, you’ve seen this. In my first posting as an infantryman, my company commander, first sergeant, platoon sergeant, and squad leader were black, a fact that I never heard anyone even mention. Rank, profession, and authority come from doing, without socioeconomic or racial chutes or ladders: If you can fly the plane, you’re a pilot. Up to the boundaries of the flag ranks, politics and identity don’t matter. (Regarding those flag ranks, see the late David Hackworth’s discussion of “perfumed princes”.)

And so the descent of the American military into the performative politics of DEI and equity and Robin DiAngelo books just blindly shits on the core value of the American military, which is that you get the rank and the status for what you do, full stop.

November 3, 2023

Understanding Combined Arms Warfare

Army University Press

Published 24 Mar 2023Designed to support the U.S. Army Captains Career Course, “Understanding Combined Arms Warfare” defines and outlines the important aspects of modern combined arms operations. This is not a complete history of combined arms warfare. It is intended to highlight the most important aspects of the subject.

The beginning of the documentary establishes a common understanding of combined arms warfare by discussing doctrinal and equipment developments in World War I. The second part compares the development of French and German Army mechanization during the interwar period and describes how each country fared during the Battle of France in 1940. The film concludes by showing how the United States applied combined arms operations in the European Theater in World War II.

(more…)

October 22, 2023

QotD: The changes in Roman legionary equipment attributed to the “Marian reforms”

There only two parts of this narrative unambiguously suggested by our sources are equipment changes: that Marius introduced a new type of pilum (Plut. Mar. 25) and that he standardized legionary standards around the aquila, the eagle standard (Plin. NH 10.16).

For the pilum, Plutarch says that Marius designed it to incorporate a wooden rivet where the long metal shank met the heavy wooden shaft, replacing one of the two iron nails with a wooden rivet that would break on impact, in order to better disable the shield. The problem is that the pilum is actually archaeologically one of the best attested Roman weapons with the result that we can follow its development fairly closely. And the late, great Peter Connolly did exactly that in a series of articles in the Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies1 and while the design of the pilum does develop over time, there’s simply no evidence for what Plutarch describes. The “broad tanged” pilum type could have been modified this way, but we’ve never found one actually so modified; instead the pila of this type we find all have rivets (two of them) in place (where rivets are preserved at all). Moreoever, most pila of that “broad tanged” type, both before and after Marius, have the edges of that broad tang bent over at the sides, which would prevent the sort of sliding action Plutarch describes even if one of the rivets broke. Meanwhile, by the first century there are three types of pila around (socketed, broad-tanged and spike-tanged) only one of which could be modified in this way (the broad-tanged type), and that type doesn’t dominate during the first century when one might expect Marius’ new-style pila to be in use. In practice then the conclusion seems to be that Plutarch made up or misunderstood this “innovation” in the pilum or, at best, the design was adopted briefly and then abandoned.

On to the aquila. Now, it is absolutely true that the aquila, the legionary eagle, became a key standard for the Roman legions. Pliny the Elder notes that before Marius it was merely the foremost of five standards, the others being the wolf, minotaur, horse and boar (Plin. HN 10.16). But even a brief glance as legionary standards into the early empire (see Keppie (1984), 205-213 for an incomplete and somewhat dated list) shows that bulls, boars and wolves remained pretty common legionary emblems (alongside the eagle) into the empire. The eagle seems to have been something of a personal totem for Marius (e.g. Plut. Mar. 36.5-6) so it is hardly surprising he’d have emphasized it, the same way that legions founded by Caesar – or which wanted to be seen as founded by Caesar – adopted the bull emblem, quite a lot. But this is a weak accomplishment, since Pliny already notes that the eagle was, even before Marius, already prima cum quattuor aliis (“first among four others”), and so it remained: first among a range of other emblems and standards. Though of all of the things we may credit Marius with instituting, this perhaps gets the closest, if we believe Pliny that Marius further elevated the eagle into its particular position.

Then there is the institution of the Roman marching pack and the furca to carry it, such that Marius’ soldiers became known as “Marius’ mules” because he made them carry all of their own kit rather than, as previous legions had supposedly done, carrying it all on mules. Surely this extremely famous element of the narrative cannot be flawed? And Plutarch sort of says this, he notes that, “Setting out on the expedition, he laboured to perfect his army as it went along, practicing the men in all kinds of running and in long marches, and compelling them to carry their own baggage and to prepare their own food. Hence, in after times, men who were fond of toil and did whatever was enjoined upon them contentedly and without a murmur, were called Marian mules” (Plut. 13.1; trans. B. Perrin). Except that doesn’t say anything about instituting the classic Roman pack that we see, for instance, depicted on Trajan’s column, does it? It just says Marius made his men carry their baggage and prepare their own food, leading to the nickname for men who did toil without complaint.

The problem is that those two things – making soldiers carry their baggage and cook their own food (along with kicking out camp followers) – are ubiquitous commonplaces of good generalship with instances that pre-date Marius. P. Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus does exactly this – getting rid of camp servants, wagons and pack animals, making soldiers cook their own food and kicking out the camp followers – according to Appian in 134 when he besieged Numantia (which fell in 133, App. Hisp. 85). And then Q. Caecilius Metellus, Marius’ own former commander, does the exact same thing in 109 when he takes command against Jugurtha in North Africa, kicking the sutlers out of the camp, getting rid of pack animals and private servants, making soldiers cook their own food, carry their own rations and their own weapons (Sall. Iug. 42.2; note that Sallust dies in in the 30s BC, 80-odd years before Plutarch is born, so Plutarch may well be getting this trope from Sallust and then attributing it to the wrong Roman). Critiques of generals who issued rations rather than making their soldiers cook or praise for generals who didn’t remained standard into the empire (e.g. Tac. Hist. 2.88; Hdn. 4.7.4-6; Dio Cass. 62.5.5). In short this trope was not new to Marius nor was it new to Plutarch’s version of Marius; it was a standard trope of generals restoring good discipline to their soldiers. Plutarch even hedges noting another story that the term “Marius’ mules” might actually have come how well Marius as a junior officer got along with animals (Plut. Mar. 13.2)!

Well, fine enough, but what about the idea that state-issued equipment is emerging in this period? Well, it might be but our evidence is not great. As noted when we discussed the dilectus, Polybius implies – and his schematic for conscription makes little sense otherwise – that the Romans are in that period buying their own equipment. He also notes that the quaestors deduct from a soldier’s pay the price of their rations (if they are Romans; socii eat for free), their clothing and any additional equipment they need (Polyb. 6.39.14). It makes sense; if a fellow forgot a sword or his breaks, you need to get that replaced, so you fine him the value of it and then issue him one from the common store.

Now Keppie (1984) assumes this system changes during the tribunate(s) of Gaius Gracchus (123-2) and you can see the temptation in this idea. If Gaius Gracchus shifts equipment to being issued at state expense, then suddenly there’s no reason not to recruit the landless proletarii (discussed below) opening the door for Marius to do so (discussed below) and fundamentally transforming the Roman army into the longer-service, professional form we see in the empire. The problem is that, well, it didn’t happen. First, we have no evidence at all that Gaius Gracchus did anything related to soldier’s arms and armor; what we have is a single line from Plutarch that soldiers should be issued clothing at state expense with nothing deducted from their pay to meet this cost (Plut. C. Gracch. 5.1). The assumption here is that this also covered arms and armor, but Plutarch doesn’t say that at all. The more fatal flaw is that we can be very, extremely sure this reform didn’t stick, because we have a bunch of Roman “pay stubs” from the imperial period (from Egypt, naturally) and regular deductions vestimentis, “for clothing” show up as standard.2 Indeed, they show up alongside deductions for food and replacement socks, boots and so on, exactly as Polybius would have us expect. Apart from the fact that this is presumably being done by a procurator instead of a quaestor (a change in the structure of administration in the provinces run directly by the emperor), this is the same system.

Now there are reasons to think that at least some equipment was state supplied or contracted (even if it may have been billed to the accounts of the soldiers who got it). Scipio creates a public armaments production center in Carthago Nova in 210, but this may be a one off. Seemingly more centralized production of arms under contract are more common in the late Republic and by the imperial period we start to see evidence of fabricae which seem to be central production sites for military equipment.3 But we have no hint in the sources of any sudden reform to this system. It may well be a gradual change as the “mix” of personal and state-ordered equipment slowly tilts in favor of the latter; the system Polybius describes could accommodate both situations, so there’s no need for a sudden big shift. Alternately, the preponderance of state-produced equipment might well be connected to the formalization of a long-service professional army under Augustus. Even then, we still find pieces of equipment in Roman imperial sites which were clearly personal; soldiers could still go and get a fancy version of standard kit, stamp their name in it and call it theirs. All I think we can say with any degree of confidence is that self-purchased equipment seems to be the norm in Polybius’ day whereas state-issued equipment seems to be the norm by the end of the first century. But Marius has nothing to do with it, as far as we can tell and no ancient source claims that he did.

Oh and by the by, if you are picking up from all of this (and our discussion of Lycurgus) that Plutarch is a difficult source that needs to be treated with a lot of caution because he never lets the facts get in the way of a good story … well, that’s true.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: The Marian Reforms Weren’t a Thing”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2023-06-30.

1. “Pilum, Gladius and Pugio in the Late Republic”, JRMES 5 (1997), then “The Reconstruction and Use of Roman Weaponry in the Second Century BC”, JRMES 11 (2000) and then “The pilum from Marius to Nero – a reconsideration of its development and function”, JRMES 12/13 (2001/2).

2. On this, see R.O. Fink, Roman Military Records on Papyrus (1971).

3. On all this, see Bishop and Coulston, Roman Military Equipment (2006), 233-240.

October 17, 2023

Why WW1 Cavalry Was Essential On The Battlefield

The Great War

Published 13 Oct 2023The First World War was a catalyst for modern warfare with tanks, poison gas, flamethrowers and more. Cavalry didn’t have a place anymore on the modern battlefield – or so the common misconception goes. In this video we show how useful cavalry still was in WW1.

(more…)

October 11, 2023

QotD: A rational army would run away …

It is a thousand years ago somewhere in Europe; you are one of a line of ten thousand men with spears. Coming at you are another ten thousand men with spears, on horseback. You do a very fast cost-benefit calculation.

If all of us plant our spears and hold them steady, with luck we can break their charge; some of us will die but most of us will live. If we run, horses run faster than we do. I should stand.

Oops.

I made a mistake; I said “we”. I don’t control the other men. If everybody else stands and I run, I will not be the one of the ones who gets killed; with 10,000 men in the line, whether I run has very little effect on whether we stop their charge. If everybody else runs I had better run too, since otherwise I’m dead.

Everybody makes the same calculation. We all run, most of us die.

Welcome to the dark side of rationality.

This is one example of what economists call market failure — a situation where individual rationality does not lead to group rationality. Each person correctly calculates how it is in his interest to act and everyone is worse off as a result.

David D. Friedman, “Making Economics Fun: Part I”, David Friedman’s Substack, 2023-04-02.