Our parents had learned some wrong lessons from the ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s. They learned to love government too well. They learned that government was what rescued you from depression and war. Our parents were very trusting of large governmental institutions. The liberalism that was a seed of the radicalism to come was in our parents, even when our parents were Republicans. They had taken large government for granted.

P.J. O’Rourke, interviewed by Scott Walter, “The 60’s Return”, American Enterprise, May/June 1997.

April 19, 2024

QotD: The “Greatest Generation”

March 13, 2024

The History of the Chocolate Chip Cookie – Depression vs WW2

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published Dec 5, 2023WWII ration-friendly chocolate chip cookies made with shortening, honey, and maple syrup

City/Region: United States of America

Time Period: 1940sDuring WWII, everyone in the US wanted to send chocolate chip cookies to the boys at the front. With wartime rationing in effect, we get a recipe that doesn’t use butter or sugar, but shortening, honey, and maple syrup instead.

The dough is much softer than the original version, and the cookies spread out a lot more as they bake. They bake up softer than the crunchy originals, with a light pillowy texture. They aren’t as sweet, but still have a really lovely flavor. It kind of reminds me of Raisin Bran, but with chocolate. All in all, I was pleasantly surprised.

Check out the episode to see a side-by-side comparison with the original recipe.

(more…)

February 1, 2024

Newfoundland – “We used to be a country”

In The Line, James McLeod outlines a difficult period for the Dominion of Newfoundland which ended up narrowly voting to join Canada rather than resume self-rule that they’d had up to 1934 when the Newfoundland House of Assembly abolished itself:

Great Riot of 1932 in front of the legislature, the Colonial Building, in Newfoundland.

Provincial Archives of Newfoundland and Labrador (Reference PANL A2-160), via Wikimedia Commons.

Before 1933, Newfoundland was proudly a dominion within the British empire. Under the Statute of Westminster, Newfoundland had the same legal status as Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and the Irish Free State.

Newfoundland was its own country. But it was a country in rough shape.

A year before the Amulree Report was published, a mob of about 10,000 people had gathered outside the Colonial Building in St. John’s. Families were living in destitution on six-cents-a-day government dole, and the government’s finance minister had just resigned and accused Prime Minister Richard Squires of personally lining his pockets with government funds.

The mob turned into a riot, which ultimately barged into the government building. Notably, the rioters briefly paused to observe a respectful silence when a brass band began playing “God Save The King”, but then they went back to rioting.

Squires fled on foot and went into hiding, and then emerged to call an election, which he lost in a landslide. During the campaign, one of his longtime allies, the prominent leader of the Fishermen’s Protective Union, openly wished for fascism.

“What is required for Newfoundland and what is most essential for the present conditions is a Mussolini,” said William Coaker.

Months later, with a new government, Newfoundland was on the verge of defaulting on its debt, and the British stepped in.

The vastly oversimplified version is that the British government was concerned that a member of the British Commonwealth defaulting on its debt could have major implications for the whole empire. So the British government bailed out Newfoundland, on the condition that a commission would be struck to investigate the island’s political and economic affairs. Lord Amulree, a British politician, was appointed as chair.

A year later, with the Dominion still teetering on the verge of bankruptcy, the Amulree Report was delivered. It contained this passage, with my emphasis added: “That it was essential that the country should be given a rest from politics for a period of years was indeed recognised by the great majority of the witnesses who appeared before us, many of whom had themselves played a prominent part in the political and public life of the Island.”

Amulree considered the possibility of some sort of national unity government, but could not get past the conclusion that, “Even if a National Government could be established on a basis which led to a suspension of political rivalry, the underlying influences which do so much to clog the wheels of administration and to divert attention from the true interests of the country would continue to form an insuperable handicap to the rehabilitation of the Island.”

In 1934, the Newfoundland House of Assembly voted itself out of existence. It was replaced by a “Commission of Government” which was just six unelected men, appointed by the British. Fifteen years later, Newfoundlanders narrowly voted to join Canada, although to this day conspiracy theories still linger about how democratic the referendum really was.

I am not a Newfoundlander, and I’m hesitant to make any sweeping statements about how Newfoundlanders relate to their own history. But for a decade, I worked as a journalist in St. John’s, covering politics and public affairs. The collapse of democratic self-rule in the 1930s still looms large in the collective identity of the province.

December 24, 2023

QotD: Dreaming of George Bailey’s world while living in Pottersville

George Bailey, the hero of It’s a Wonderful Life, missed the two events that made the ideal man of his time, place, and social class: going to college and serving (as an officer, of course) in the Second World War. Instead of doing those things, either of which would have sent him out into the world beyond the limits of Bedford Falls, he remained at home, taking care of his family, his business, and his community. In other words, the hero of America’s favorite exercise in Yuletide nostalgia epitomized a way of life that, in the season of the film’s cinematic debut (the summer of 1946), was already on its way to the dustbin of history.

This, the most enduring of the many works of Frank Capra, became the Atlantis myth of post-war America. That is, those who, over the course of the last half-century, saw It’s a Wonderful Life on television, knew well that the age of community and connection depicted on their screens had already passed into the realm of legend. Moreover, to add injury to insult, they also knew that, if they wished to enjoy the fruits of a middle-class existence, they would have to live in the manner of vagabonds.

In the movie, slum-lord Henry Potter tries, but fails, to turn the provincial paradise of Bedford Falls into a run-down haunt of spinsters, drunks, and floozies. In the real world, it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who put the kibosh on the original Main Street, USA. To be more precise, the principal achievements of America’s greatest tyrant, the Great Depression and the Second World War, undermined the financial, legal, and cultural foundations of the “wonderful life”. Thus, by the time this process had run its course, inflation had made a fool’s game of simple thrift, the replacement of law with regulation had hobbled private enterprise, and people who had left home for the sake of college, work, or military service found themselves lost in a sea of strangers.

In response to these changes, colleges and universities stepped up to the proverbial plate, happy to offer substitutes for the things that had been lost. They gave young people a chance to obtain certificates that would attest to both their suitability for service in the ranks of corporate minions and their social respectability. At the same time, these institutions gave older people a way to convert their value-losing cash into an asset that promised to pay dividends that would benefit their children (and, indeed, their grandchildren) for decades to come.

Thus arose the people I have come to call the MICE (Mobile, Individualistic, College Educated) people. Bereft of regional accents, productive property, and deep connections to friends and relations, they wandered the world, building networks, acquiring degrees, and padding resumés. However, after two generations of such peripatetic solipsism, the age of the MICE people is coming to an end.

Young men of parts, who realize that college has nothing to do with either liberal learning or vocational training, are simultaneously taking up skilled trades and stocking their MP3 players with learned podcasts. At the same time, young women of quality are beginning to think that the traditional troika of Kirche, Küche, und Kinder offers better odds of deep satisfaction than life as a hormone-hobbled, Starbucks swilling, girl boss.

So, if you know young people like the ones I’ve just described, do posterity a favor, and put them in contact with each other. After all, they deserve a life as wonderful as that of George and Mary Bailey.

Bruce Ivar Gudmundsson, “College, Class, and Christmas”, Extra Muros, 2023-08-06.

October 11, 2023

Art Deco in 9 Minutes: Why Is It The Most Popular Architectural Style? 🗽

Curious Muse

Published 3 Sept 2021What comes to your mind when you think of the 1920s? For most people, the 1920s conjures up images of jazz, flappers, Old Hollywood, the Great Gatsby, and the Chrysler Building in New York City. It was a time of prosperity, exorbitant spending, and entertainment that gave rise to one of the most popular decorative arts and architecture movements — known as Art Deco.

Characterized by exquisite craftsmanship, lavish decoration, and rich materials, the style has become synonymous with the Roaring Twenties. So, what was the Art Deco movement all about and what differentiates it from other major movements? Finally, despite its popularity today, what makes Art Deco so closely associated with the 1920s?

In this week’s video, we’ll dive into the history of the era and learn about Art Déco, the style that continues to inspire designers and architects around the world!

(more…)

June 13, 2023

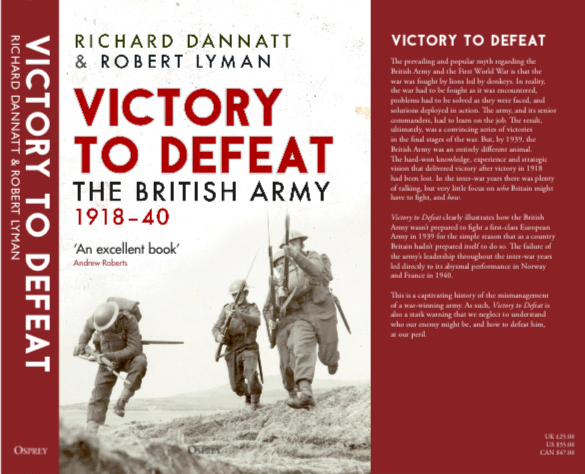

After the Great War, the British army failed to plan for future conflicts

Robert Lyman outlines why Britain in general and the British army in particular were so materially and intellectually unready for the war that broke out in 1939:

… the British Army was catastrophically unprepared for war in 1939. But it wasn’t just the Army that was unprepared. Despite a last-minute rush to re-arm, so too was the whole country. In Britain a deep-seated passivity had set in following the end the Great War. This belied the reality that in Europe the ending of the war in fact opened the door to unheralded political chaos and instability that was in time to overcome the forces of stability and would lead directly to yet another devastating war. In the years immediately following the arrival of peace in 1918 Britain hoped it could close the door on any future European or continent commitment and return to the halcyon days when its only security commitments were the defence of its widely flung Empire.

The weakness at the heart of British planning for war was a direct reflection of Britain’s strategic, political, societal and economic situation during the inter-war period. Britain – both the British public and the country’s various governments – simply wasn’t mentally prepared to go to war again so soon after the trauma of the Great War. As a result, it made no proper preparation for another full-on industrial war against a peer opponent on the continent. This was fundamentally a failure of political and military imagination; the inability to think through what a potential war might look like and to prepare for this possibility accordingly.

We have identified five primary causes of the decline of British military effectiveness in 1939. In the first place there was no clear strategic plan for the Army. Strategies are determined by having a clear understanding of who a future enemy might be. Following the end of the Great War, until the late 1930s no one seemed bothered to define this essential point of direction. There was a remarkably inadequate grand strategic conversation (i.e., at a national, governmental level) about the purpose, structure, and nature of the Army. There was plenty of talking, but very little of it focused on realistic determination as to who it might have to fight, and how. This was a problem, because it meant that Britain was unable to determine the precise structure its armed forces needed to be, and its cost. Was the focus of the army to be the continent, or the Empire, or both? No one knew. As a result, the last known plan reasserted itself – Imperial defence, à la 1914. This meant that the army wasn’t structured or equipped to fight a specified enemy in a defined set of circumstances. Instead, the British Army and its cousin, the Indian Army, was expected to be a generic jack-of-all-trades, without the structure, doctrine, training, or equipment to fight the type of war it had become the master of in 1918. While there was some doctrine, and considerable doctrinal debate, little was anchored in a clear definition of what future war was expected to look like. There was no operational design for the British Army derived directly from an analysis of the threat it faced. If it had done, the BEF would have been thoroughly prepared for the German Blitzkrieg in France and the Low Countries in 1940 or the similar Japanese Kirimoni Sakusen in 1941 and 1942. The British Army wasn’t prepared to fight a first-class European Army in 1939 for the simple reason that Britain hadn’t prepared itself to do so. Likewise, when it came to fighting the Japanese in 1941 and 1942 in Malaya and Burma, the British found that not only had it failed to prepare adequately for a potential Japanese invasion of its vulnerable Far Eastern colonies, but that it had no idea as to how to fight the Imperial Japanese Army. There were two connected failures here. The first was one of strategic preparedness, the blame for which was both governmental and strategic. The second was of training, doctrine and military preparedness by the British Army in Europe and Asia to fight. When they emerged out of their assault boats at Kota Bahru on the morning of 8 December 1942 the Japanese could as well have come from Mars, given how little the British knew about them and their warfighting methods.

Second, as a country, Britain was unprepared both politically and culturally for another war so soon after the last. In 1919 the country seemed to want to look backward to embrace the days of peace that had preceded the cataclysm of war, to drape itself with Edwardian comfort. It was tired and disillusioned, and felt no victor’s triumph. The country looked to itself, and to its Empire, eschewing the complications of commitments on continental Europe that had recently resulted in the loss of so much blood. The losses sustained in the Great War resulted in the overwhelming national sentiment that war must never again be undertaken as a form of politics. Clausewitz was dead. Part of this sentiment evidenced itself in the rise of pacifism. In the army, a pervasive belief existed that the Great War was an aberration, and nothing like it would again afflict western civilisation. Any lessons from the war were therefore irrelevant to the future structures or doctrine of the British Army, for whom the defence of the Empire was the crucial issue. But whether it liked it or not, the world was changing fast, in ways that Britain struggled to comprehend and from which it could not ultimately escape. The Russian Revolution, the rise of fascist dictators in Europe, isolationism in the USA (except for a new American assertiveness in Asia) and the increasing militancy of Japan, began changing the global landscape in ways that were hard to understand for a country seemingly once in total charge of the certainties of statecraft. Now it struggled to find its way in a new world of tension, turmoil and rapid change.

Third, no one in the British Army thought to capture the reasons for operational success in 1918. The dramatic reduction in troops numbers at the end of the Great War meant that those best able to convert the learning from 1918 into doctrine left for civilian life, taking their knowledge and experience with them. It was never recovered. There was therefore no template in the years afterward on which to build a successful military doctrine based on the successful warfighting experience that had culminated in the victories of 1918.

Fourth, political naivety led to a dramatic economic stringency being applied, including the underlying Treasury assumption in the early 1920’s of the ‘Ten Year Rule’, an assumption that kept rolling over, year after year. This meant that there wasn’t enough money to do what was necessary to protect British interests from impending harm. The Army butter was thinly spread on the imperial bread, with the result that insufficient investment was made in the core of the army’s warfighting capability. This stringency was exacerbated by the impact of the Great Depression at the end of the 1920s into the early years of the next decade.

March 1, 2023

School Lunch from the Great Depression

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 28 Feb 2023

(more…)

January 11, 2023

Al Capone’s Soup Kitchen

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 10 Jan 2023

(more…)

September 2, 2022

The winner in 1932 campaigned against high taxes, big government, and more debt. Then he turned all those up to 11

At the Foundation for Economic Education, Lawrence W. Reed notes that we often get the opposite of what we vote for, and perhaps the best example of that was the 1932 presidential campaign between high-taxing, big-spending, government-expanding Republican Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who ran against all of Hoover’s excesses … until inauguration day, anyway:

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: FDR (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) was responsible for the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal’s WPA program.

Wikimedia Commons.

If you were a socialist (or a modern “liberal” or “progressive”) in 1932, you faced an embarrassment of riches at the ballot box. You could go for Norman Thomas. Or perhaps Verne Reynolds of the Socialist Labor Party. Or William Foster of the Communist Party. Maybe Jacob Coxey of the Farmer-Labor Party or even William Upshaw of the Prohibition Party. You could have voted for Hoover who, after all, had delivered sky-high tax rates, big deficits, lots of debt, higher spending, and trade-choking tariffs in his four-year term. Roosevelt’s own running mate, John Nance Garner of Texas, declared that Republican Hoover was “taking the country down the path to socialism”.

Journalist H.L. Mencken famously noted that “Every election is a sort of advance auction sale of stolen goods.” If you agreed with Mencken and preferred a non-socialist candidate who promised to get government off your back and out of your pocket in 1932, Franklin Roosevelt was your man — that is, until March 1933 when he assumed office and took a sharp turn in the other direction.

The platform on which Roosevelt ran that year denounced the incumbent administration for its reckless growth of government. The Democrats promised no less than a 25 percent reduction in federal spending if elected.

Roosevelt accused Hoover of governing as though, in FDR’s words, “we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible.” On September 29 in Iowa, the Democrat presidential nominee blasted Hooverism in these terms:

I accuse the present Administration of being the greatest spending Administration in peace times in all our history. It is an Administration that has piled bureau on bureau, commission on commission, and has failed to anticipate the dire needs and the reduced earning power of the people. Bureaus and bureaucrats, commissions and commissioners have been retained at the expense of the taxpayer.

Now, I read in the past few days in the newspapers that the President is at work on a plan to consolidate and simplify the Federal bureaucracy. My friends, four long years ago, in the campaign of 1928, he, as a candidate, proposed to do this same thing. And today, once more a candidate, he is still proposing, and I leave you to draw your own inferences. And on my part, I ask you very simply to assign to me the task of reducing the annual operating expenses of your national government.

Once in the White House, he did no such thing. He doubled federal spending in his first term. New “alphabet agencies” were added to the bureaucracy. Nothing of any consequence in the budget was either cut or made more efficient. He gave us our booze back by ending Prohibition, but then embarked upon a spending spree that any drunk with your wallet would envy. Taxes went up in FDR’s administration, not down as he had promised.

Don’t take my word for it. It’s all a matter of public record even if your teacher or professor never told you any of this. For details, I recommend these books: Burton Folsom’s New Deal or Raw Deal; Murray Rothbard’s America’s Great Depression; my own Great Myths of the Great Depression; and the two I want to tell you about now, John T. Flynn’s As We Go Marching and The Roosevelt Myth.

For every thousand books written, perhaps one may come to enjoy the appellation “classic”. That label is reserved for a volume that through the force of its originality and thoroughness, shifts paradigms and serves as a timeless, indispensable source of insight.

Such a book is The Roosevelt Myth. First published in 1948, Flynn’s definitive analysis of America’s 32nd president is arguably the best and most thoroughly documented chronicle of the person and politics of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Flynn’s 1944 book, As We Go Marching, focuses on the fascist-style economic planning during World War II and is very illuminating as well.

July 6, 2022

September 27, 2021

QotD: The functions of the state

The great trouble today is that we have too many laws. I believe that primarily a government has but two functions — to protect the lives and property rights of citizens. When it goes further than that, it becomes a burden.

John Nance Garner, Vice President of the United States 1933-1937.

September 2, 2021

Road to WWII: A Basic Causal Analysis

Thersites the Historian

Published 19 Nov 2019This video is a primer for undergraduates in broad history survey courses that will hopefully help make sense of the interwar years between World War I and World War II.

Patreon link: https://www.patreon.com/thersites

PayPal link: paypal.me/thersites

Twitter link: https://twitter.com/ThersitesAthens

Minds.com link: https://www.minds.com/ThersitestheHis…

Steemit/dtube link: https://steemit.com/@thersites/feed

BitChute: https://www.bitchute.com/channel/jbyg…

Backup Channel: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCUrD…

August 10, 2020

FDR’s “New Deal” and the Great Depression

The Great Depression began with the collapse of the stock market in 1929 and was made worse by the frantic attempts of President Hoover to fix the problem. Despite the commonly asserted gibe that Hoover tried laissez faire methods to address the economic crisis, he was a dyed-in-the-wool progressive and a life-long control freak (the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act which devasted world trade was passed in 1930). Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1932 election by promising to undo Hoover’s economic interventions, yet once in office he turned out to be even more of a control freak than Hoover. His economic and political plans made Hoover’s efforts seem merely a pale shadow.

For newcomers to this issue, “New Deal” is the term used to describe the various policies to expand the size and scope of the federal government adopted by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt (a.k.a., FDR) during the 1930s.

And I’ve previously cited many experts to show that his policies undermined prosperity. Indeed, one of my main complaints is that he doubled down on many of the bad policies adopted by his predecessor, Herbert Hoover.

Let’s revisit the issue today by seeing what some other scholars have written about the New Deal. Let’s start with some analysis from Robert Higgs, a highly regarded economic historian.

… as many observers claimed at the time, the New Deal did prolong the depression. … FDR and Congress, especially during the congressional sessions of 1933 and 1935, embraced interventionist policies on a wide front. With its bewildering, incoherent mass of new expenditures, taxes, subsidies, regulations, and direct government participation in productive activities, the New Deal created so much confusion, fear, uncertainty, and hostility among businessmen and investors that private investment, and hence overall private economic activity, never recovered enough to restore the high levels of production and employment enjoyed in the 1920s. … the American economy between 1930 and 1940 failed to add anything to its capital stock: net private investment for that eleven-year period totaled minus $3.1 billion. Without capital accumulation, no economy can grow. … If demagoguery were a powerful means of creating prosperity, then FDR might have lifted the country out of the depression in short order. But in 1939, ten years after its onset and six years after the commencement of the New Deal, 9.5 million persons, or 17.2 percent of the labor force, remained officially unemployed.

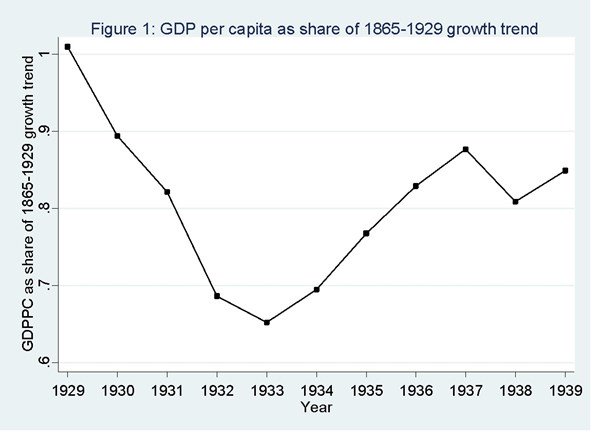

Writing for the American Institute for Economic Research, Professor Vincent Geloso also finds that FDR’s New Deal hurt rather than helped.

… let us state clearly what is at stake: did the New Deal halt the slump or did it prolong the Great Depression? … The issue that macroeconomists tend to consider is whether the rebound was fast enough to return to the trendline. … The … figure below shows the observed GDP per capita between 1929 and 1939 expressed as the ratio of what GDP per capita would have been like had it continued at the trend of growth between 1865 and 1929. On that graph, a ratio of 1 implies that actual GDP is equal to what the trend line predicts. … As can be seen, by 1939, the United States was nowhere near the trendline. … Most of the economic historians who have written on the topic agree that the recovery was weak by all standards and paled in comparison with what was observed elsewhere. … there is also a wide level of agreement that other policies lengthened the depression. The one to receive the most flak from economic historians is the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA). … In essence, it constituted a piece of legislation that encouraged cartelization. By definition, this would reduce output and increase prices. As such, it is often accused of having delayed recovery. … other sets of policies (such as the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the National Labor Relations Act and the National Industrial Recovery Act) … were very probably counterproductive.

Here’s one of the charts from his article, which shows that the economy never recovered lost output during the 1930s.

April 20, 2020

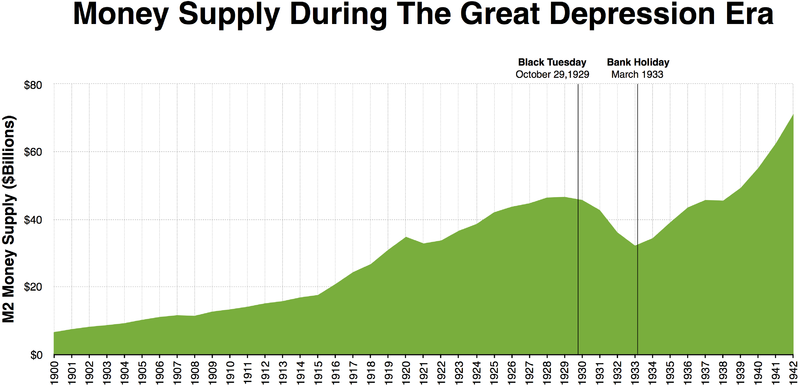

The four distinct phases of the Great Depression in the United States

An older post from Lawrence W. Reed at the Foundation for Economic Education outlines the low points of the Great Depression and debunks a few widely held myths about that cataclysmic economic era:

Phase 1, the Federal Reserve and the end of the Roaring 20’s:

One of the most thorough and meticulously documented accounts of the Fed’s inflationary actions prior to 1929 is America’s Great Depression by the late Murray Rothbard. Using a broad measure that includes currency, demand and time deposits, and other ingredients, Rothbard estimated that the Federal Reserve expanded the money supply by more than 60 percent from mid-1921 to mid-1929. The flood of easy money drove interest rates down, pushed the stock market to dizzy heights, and gave birth to the “Roaring Twenties.”

By early 1929, the Federal Reserve was taking the punch away from the party. It choked off the money supply, raised interest rates, and for the next three years presided over a money supply that shrank by 30 percent. This deflation following the inflation wrenched the economy from tremendous boom to colossal bust.

The “smart” money — the Bernard Baruchs and the Joseph Kennedys who watched things like money supply — saw that the party was coming to an end before most other Americans did. Baruch actually began selling stocks and buying bonds and gold as early as 1928; Kennedy did likewise, commenting, “only a fool holds out for the top dollar.”

Phase 2, Hoover’s interventions and the disaster of Smoot-Hawley:

Willis C. Hawley (left) and Reed Smoot in April 1929, shortly before the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act passed the House of Representatives.

Library of Congress photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Unemployment in 1930 averaged a mildly recessionary 8.9 percent, up from 3.2 percent in 1929. It shot up rapidly until peaking out at more than 25 percent in 1933. Until March 1933, these were the years of President Herbert Hoover — the man that anti-capitalists depict as a champion of noninterventionist, laissez-faire economics.

Did Hoover really subscribe to a “hands off the economy,” free-market philosophy? His opponent in the 1932 election, Franklin Roosevelt, didn’t think so. During the campaign, Roosevelt blasted Hoover for spending and taxing too much, boosting the national debt, choking off trade, and putting millions of people on the dole. He accused the president of “reckless and extravagant” spending, of thinking “that we ought to center control of everything in Washington as rapidly as possible,” and of presiding over “the greatest spending administration in peacetime in all of history.” Roosevelt’s running mate, John Nance Garner, charged that Hoover was “leading the country down the path of socialism.” Contrary to the modern myth about Hoover, Roosevelt and Garner were absolutely right.

The crowning folly of the Hoover administration was the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, passed in June 1930. It came on top of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff of 1922, which had already put American agriculture in a tailspin during the preceding decade. The most protectionist legislation in U.S. history, Smoot-Hawley virtually closed the borders to foreign goods and ignited a vicious international trade war. Professor Barry Poulson notes that not only were 887 tariffs sharply increased, but the act broadened the list of dutiable commodities to 3,218 items as well.

Officials in the administration and in Congress believed that raising trade barriers would force Americans to buy more goods made at home, which would solve the nagging unemployment problem. They ignored an important principle of international commerce: trade is ultimately a two-way street; if foreigners cannot sell their goods here, then they cannot earn the dollars they need to buy here.

Phase 3, FDR and the New Deal:

Top left: The Tennessee Valley Authority, part of the New Deal, being signed into law in 1933.

Top right: FDR (President Franklin Delano Roosevelt) was responsible for the New Deal.

Bottom: A public mural from one of the artists employed by the New Deal’s WPA program.

Wikimedia Commons.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election in a landslide, collecting 472 electoral votes to just 59 for the incumbent Herbert Hoover. The platform of the Democratic Party whose ticket Roosevelt headed declared, “We believe that a party platform is a covenant with the people to be faithfully kept by the party entrusted with power.” It called for a 25 percent reduction in federal spending, a balanced federal budget, a sound gold currency “to be preserved at all hazards,” the removal of government from areas that belonged more appropriately to private enterprise, and an end to the “extravagance” of Hoover’s farm programs. This is what candidate Roosevelt promised, but it bears no resemblance to what President Roosevelt actually delivered.

In the first year of the New Deal, Roosevelt proposed spending $10 billion while revenues were only $3 billion. Between 1933 and 1936, government expenditures rose by more than 83 percent. Federal debt skyrocketed by 73 percent.

[…] in 1935 the Works Progress Administration came along. It is known today as the very government program that gave rise to the new term, “boondoggle,” because it “produced” a lot more than the 77,000 bridges and 116,000 buildings to which its advocates loved to point as evidence of its efficacy. The stupefying roster of wasteful spending generated by these jobs programs represented a diversion of valuable resources to politically motivated and economically counterproductive purposes.

The American economy was soon relieved of the burden of some of the New Deal’s excesses when the Supreme Court outlawed the NRA in 1935 and the AAA in 1936, earning Roosevelt’s eternal wrath and derision. Recognizing much of what Roosevelt did as unconstitutional, the “nine old men” of the Court also threw out other, more minor acts and programs which hindered recovery.

Phase 4, the Wagner Act:

The stage was set for the 1937–38 collapse with the passage of the National Labor Relations Act in 1935 — better known as the Wagner Act and organized labor’s “Magna Carta.” […] Armed with these sweeping new powers, labor unions went on a militant organizing frenzy. Threats, boycotts, strikes, seizures of plants, and widespread violence pushed productivity down sharply and unemployment up dramatically. Membership in the nation’s labor unions soared; by 1941 there were two and a half times as many Americans in unions as in 1935.

[…]

Higgs draws a close connection between the level of private investment and the course of the American economy in the 1930s. The relentless assaults of the Roosevelt administration — in both word and deed — against business, property, and free enterprise guaranteed that the capital needed to jumpstart the economy was either taxed away or forced into hiding. When Roosevelt took America to war in 1941, he eased up on his antibusiness agenda, but a great deal of the nation’s capital was diverted into the war effort instead of into plant expansion or consumer goods. Not until both Roosevelt and the war were gone did investors feel confident enough to “set in motion the postwar investment boom that powered the economy’s return to sustained prosperity.”

April 15, 2020

When the Fed Does Too Much

Marginal Revolution University

Published 22 Aug 2017In the 2000s, the Fed kept interest rates low to stimulate aggregate demand. But the cheap credit also helped fuel the housing market bubbles. We’ll look at the case of the Great Recession as an example of where the Fed did too much in one area, and perhaps not enough in others.