… given this general lack of geographical knowledge, try to imagine embarking on a voyage of discovery. To an extent, you might rely on the skill and experience of your mariners. For England in the mid-sixteenth century, however, these would not have been all that useful. It’s strange to think of England as not having been a nation of seafarers, but this was very much the case. Its merchants in 1550 might hop across the channel to Calais or Antwerp, or else hug the coastline down to Bordeaux or Spain. A handful had ventured further, to the eastern Mediterranean, but that was about it. Few, if any, had experience of sailing the open ocean. Even trade across the North Sea or to the Baltic was largely unknown – it was dominated by the German merchants of the Hanseatic League. Nor would England have had much to draw upon in the way of more military, naval experience. The seas for England were a traditional highway for invaders, not a defensive moat. After all, it had a land border with Scotland to the north, as well as a land border with France to the south, around the major trading port of Calais. Rather than relying on the “wooden walls” of its ships, as it would in the decades to come, the two bulwarks in 1550 were the major land forts at Calais and Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Anton Howes, “The House of Trade”, Age of Invention, 2019-11-13.

April 22, 2024

QotD: Before England could rely on the “wooden walls” of the Royal Navy

April 19, 2024

The Führerbunker – Hitler’s Grave

World War Two

Published 18 Apr 2024The man who once conquered Europe, Adolf Hitler, now cowers underground in the Führerbunker as bombs and artillery rain down on the ruins of the Reich. Today Sparty gives you a tour of the damp and claustrophobic concrete maze that will soon become the dictator’s coffin.

(more…)

April 18, 2024

What to do if Romans Sack your City

toldinstone

Published Jan 12, 2024Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:34 Progress of a siege

1:55 Looting and violence

3:42 Recorded atrocities

4:45 Captives

5:27 BetterHelp

6:36 Surviving a Roman sack

7:13 Where to hide

8:27 What to do if you’re captured

9:20 Advice for women

10:09 The fate of captives

(more…)

March 27, 2024

The Volkssturm – a Million men to save the Reich?

World War Two

Published 26 Mar 2024The Volkssturm is the last-ditch people’s army of the Third Reich. Sure, on paper, there are millions of old men and boys ready to defend Germany. But how will they be armed? Are they truly willing to die for Hitler? Will they make any difference at all?

(more…)

March 23, 2024

The Roman Army’s Biggest Building Projects

toldinstone

Published Dec 15, 2023The greatest achievements of the Roman military engineers.

Chapters:

0:00 Introduction

0:38 Marching camps

1:36 Bridges

2:40 Siegeworks

3:26 PIA VPN

4:32 Permanent forts

5:49 Roads

6:24 Frontier defenses

7:41 Canals

8:21 Civilian projects

8:54 The aqueduct of Saldae

(more…)

March 2, 2024

QotD: Early siege warfare

Now the besieger’s side of the equation may seem like an odd place to start a primer on fortifications, but it actually makes a fair bit of sense, because the capabilities of a potential attacker is where most thinking about fortification begins. Siegecraft, both offensive and defensive, is a case of “antagonistic co-evolution“, a form of evolution through opposition where each side of the relationship evolves new features in response to the other: neither offensive siege techniques nor fortifications evolve in isolation but rather in response to each other.

In many ways the choice of where to begin following that process of evolution is arbitrary. We could in theory start anywhere from the very distant past or only very recently, but in this case I think it makes sense to begin with the early Near Eastern iron age because of the nature of our evidence. While it is clear that siege warfare must have been an important part of not only bronze age warfare but even pre-bronze age warfare, sources for the details of its practice in that era are sparse (in part because, as we’ll see, siege warfare was a sort of job done by lower status soldiers who often didn’t figure much into artwork focused on royal self-representation and legitimacy-building).

But as we move into the iron age, the dominant power that emerges in the Near East is the (Neo-)Assyrian Empire, the rulers of which make a point of foregrounding their siegecraft as part of a broader program of discouraging revolt by stressing the fearsome abilities of the Assyrian army (which in turn had much of its strength in its professional infantry). Consequently, we have some very useful artistic depictions of the Assyrian army doing siege work and at the same time some incomplete but still very useful information about the structure of the army itself. Moreover, it is just as the Assyrian Empire’s day is coming to a close (collapse in 609) that the surviving source base begins to grow markedly more robust (particularly, but not exclusively, in Greece), giving us dense descriptions of siege work (and even some manuals concerning it) in the following centuries, which we can in turn bring to the Assyrian evidence to better understand it. So this is a good place to start because it is the earliest point where we are really on firm ground in terms of understanding siegecraft in some detail. This does mean we are starting in medias res, with sophisticated states already using complex armies to assault fairly complex, sophisticated fortifications, which is worth keeping in mind.

That said, it should be noted that this is hardly beginning at the beginning. The earliest fortifications in most regions of the world were wooden and probably very simple (often just a palisade with perhaps an elevated watch-post), but by the late 8th century, well-defended sites (like walled cities) already sported sophisticated systems of stone walls and towers for defense. That caveat is in turn necessary because siegecraft didn’t evolve the same way everywhere: precisely because this is a system of antagonistic co-evolution it means that in places where either offensive or defensive methods (or technologies) took a different turn, one can end up with very different results down the line (something we’ll see especially with gunpowder).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part I: The Besieger’s Playbook”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-10-29.

March 1, 2024

Was JUNO BEACH The Deadliest On D Day? | Canadian Army | Normandy WW2

The History Explorer

Published Oct 27, 2023During the invasion of Fortress Europe the casualty figures sustained on Omaha beach were terrifying; approximately 2,500 US casualties were sustained of which around 800 were killed, depending on which source you use. The ratio was said to be 1 in 19 soldiers would become a casualty.

But it was at Juno beach where the fighting Canadians landed that the casualties were 1 in 18. The fighting on Juno beach resembled modern urban warfare – silencing fortified residential houses, clearing rooms and bunker busting. So was this the more deadly beach? This is the story, of Juno beach and the brave sons of Canada.

On June 6th, 1944, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 2nd Armoured Brigade were tasked with establishing a bridgehead on the beach codenamed “Juno”. This was an eight-kilometre long stretch of beach between Sword beach to the East and Gold beach to the West.

Come with me as we walk the beaches and take a look at what made this beach so well defended.

(more…)

February 28, 2024

Why Germany Lost the First World War

The Great War

Published Nov 10, 2023Germany’s defeat in the First World War has been blamed on all kinds of factors or has even been denied outright as part of the “stab in the back” myth. But why did Germany actually lose?

(more…)

February 10, 2024

“Ukraine is running out of soldiers to man the front”

In the second part of his review of the situation in the Russo-Ukrainian War, Niccolo Soldo discusses why the plight of Ukraine’s military is getting worse, not better:

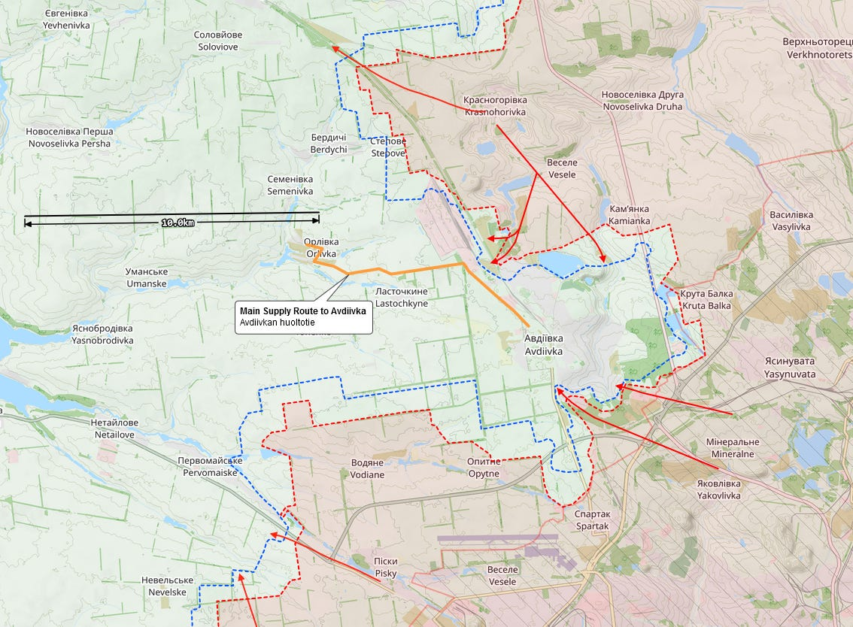

Since the previous entry was published, several key developments continue to make the outlook for Ukraine even gloomier than it already was then. The Ukrainian-held city of Avdiivka is now falling to Russian forces. This city is right next to Donetsk, the largest city in the Donbass. It is from Avdiivka that the Ukrainian Armed Forces (UAF) have been shelling that city for almost a decade now. It is considered by many to be the location with the strongest fortifications along the entire front line. Its capture by the Russians would be a significant victory, not just because of the size of the battle, but especially because it would spare the city of Donetsk from any future artillery barrages from the Ukrainian side.

Since the last entry, the ongoing fight between President Zelensky and his top general, Valeri Zaluzhny, has broken out into the open. Zelensky has indicated that he will be replacing Zaluzhny (and others) in order to “shake up” Ukraine’s war effort, a move that the general refuses to accept. The two Z’s do not see eye-to-eye, with observers informing us that Zaluzhny has called for the UAF to pull out of Avdiivka in order to buy time and not lose more men and arms in defending a city that they would lose in due time. [NR: Zelensky announced that Oleksandr Syrsky has replaced Zaluzhny on February 9th.]

Making matters even worse for the Ukrainians, the US Senate failed to agree to send more money to Kiev to help them in their fight against the Russians. Ukrainian officials told the Guardian that the failure in the US Senate “… will have real consequences in terms of lives on the battlefield and Kyiv’s ability to hold off Russian forces on the frontline”. US Aid For Ukraine President Yuriy Boyechko sounded an even gloomier note:

Everyone was hoping that US won’t let us down, and now we find ourselves at a very difficult place. People are losing hope little by little. We don’t have time for this because we see what’s going on at the front. The more time we give for the Russians to build up their stockpiles, even if the aid is going to show up it might be too little too late.

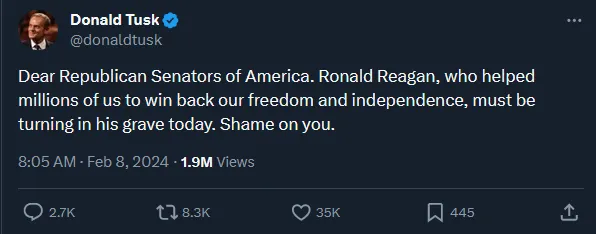

Newly-elected Polish Premier Donald Tusk criticized Senate Republicans by invoking the memory of Ronald Reagan:

And not to be outdone, Politico is blaming who else but Donald Trump.

The EU did finally manage to convince Hungary to agree to a new 50 Billion EUR package for Ukraine, but European leaders all agree that it is “nowhere near enough”, and requires the USA to chip in just as much as a minimum to sustain the war effort. This package is to be spread out until 2027, but Ukraine faces a funding shortfall of 40 Billion USD this year alone! From the linked article:

“Everyone realizes that €50 billion is not enough,” said Johan Van Overtveldt, a Belgian conservative who chairs the European Parliament’s Budget Committee. “Europe realizes that it needs to step up its efforts.” And by that, he means finding money from elsewhere.

World Bank estimates put Ukraine’s long-term needs for reconstruction at $411 billion.

Money is one thing (and a very, very important thing at that), but all the money in the world doesn’t address the elephant in the room: Ukraine is running out of soldiers to man the front.

February 1, 2024

The Kohima Epitaph: Britain’s Forgotten Battle That Changed WW2

The History Chap

Published 9 Nov 2023What is the Kohima Epitaph and what has it got to do with Britain’s forgotten battle that changed the Second World War? Well, those of you living in the UK and who attend Remembrance Sunday services will probably know the words even if you don’t know the story behind them:

“When you go home, tell them of us and say,

For your tomorrow, We gave our today.”The memorial which bears those powerful words, stands in a cemetery containing the graves over over 1,400 British servicemen and memorials to over 900 Indian troops who died alongside them. They died in one of the bloodiest, toughest, grimmest battles of the Second World War. A battle sometimes called the “Stalingrad of the East.”

Outnumbered 6:1 and half of whom were from non-combat units, the multi-national British garrison stood their ground in bloody hand-to-hand fighting, refusing to retreat or surrender for two weeks until relieved. And even then the battle continued for another vicious month. That stand stopped the Japanese invasion of India in its tracks and turned the tide of the war in South East Asia. Both for its ferocity and its turning point in the war, it has been called: “Britain’s greatest battle”.

The Japanese lost 53,000 men from their army of 85,000.

The British (14th Army) lost 4,000 men killed and wounded.This forgotten victory was made possible by General William (Bill) Slim commanding the 14th Army. Rather like the battle and the 14th Army, General Slim has not received the recognition that he is due. And yet, it is almost completely forgotten. Rather like the army that fought against the Japanese in Burma.

So, as we near Remembrance Sunday, I think it is time to reveal the story of the Battle of Kohima in 1944.

(more…)

December 30, 2023

Building the Walls of Constantinople

toldinstone

Published 15 Sept 2023This video, shot on location in Istanbul, explores the walls of Byzantine Constantinople — and describes how they finally fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

(more…)

December 21, 2023

The Battle of Ortona

Army University Press

Published 20 Dec 2023Between 20 and 28 December 1943, the idyllic Adriatic resort town of Ortona, Italy was the scene of some of the most intense urban combat in the Mediterranean Theater. Soldiers of the First Canadian Infantry Division fought German Falschirmjager for control of the city, the eastern anchor of the Gustav Line. The Army University Films Team is proud to present, The Battle of Ortona, as told by Major Jayson Geroux of the Canadian Armed Forces.

December 14, 2023

QotD: The rise of castles in early Medieval Europe

While fortifications obviously had existed a long time, when we talk about castles, what we really mean is a kind of fortified private residence which also served as a military base. This form of fortification really only becomes prominent (as distinct from older walled towns and cities) in 9th century, in part because the collapse of central authority (due in turn to the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire) led to local notables fortifying their private residences. This process was, unsurprisingly, particularly rapid and pronounced in the borderlands of the various Carolingian splinter kingdoms (where there were peer threats from the other splinters) and in areas substantially exposed to Scandinavian (read: Viking) raiding. And so functionally, a castle is a fortified house, though of course large castles could encompass many other functions. In particular, the breakdown of central authority meant that these local aristocrats also represented much of the local government and administration, which they ran not through a civil bureaucracy but through their own households and so in consequence their house (broadly construed) was also the local administrative center.

Now, we can engage here in a bit of a relatable thought experiment: how extensively do your fortify your house (or apartment)? I’ll bet the answer is actually not “none” – chances are your front door locks and your windows are designed to be difficult to open from the outside. But how extensive those protections are vary by a number of factors: homes in high crime areas might be made more resistant (multiple deadbolts, solid exterior doors rather than fancy glass-pane doors, possibly even barred windows at ground level). Lots of neighbors can lower the level of threat for a break-in, as can raw obscurity (as in a house well out into the country). Houses with lots of very valuable things in them might invest in fancy security systems, or at least thief deterring signs announcing fancy security systems. And of course the owner’s ability to actually afford more security is a factor. In short, home defenses respond to local conditions aiming not for absolute security, but for a balance of security and cost: in safe places, home owners “consume” that security by investing less heavily in it, while homeowners who feel less safety invest more in achieving that balance, in as much as their resources allow. And so the amount of security for a house is not a universal standard but a complicated function of the local danger, the resources available and the individual home owner’s risk tolerance. Crucially, almost no one aims for absolute home security.

And I go through this thought process because in their own way the same concerns dictate how castles – or indeed, any fortification – is constructed, albeit of course a fortified house that aims to hold off small armies rather than thieves is going to have quite a bit more in the way of defenses than your average house. No fortification is ever designed to be absolutely impenetrable (or perhaps most correctly put, no wise fortress designer ever aims at absolute impenetrability; surely some foolish ones have tried). This is a fundamental mistake in assessing fortifications that gets made very often: concluding that because no fortification can be built to withstand every assault, that fortification itself is useless; but withstanding every assault is not the goal. The goal is not to absolutely prohibit every attack but merely to raise the cost of an attack above either a potential enemy’s willingness to invest (so they don’t bother) or above their ability to afford (so the attack is attempted and fails) and because all of this is very expensive the aim is often a sort of minimum acceptable margin of security against an “expected threat” (which might, mind you, still be a lot of security, especially if the “expected threat” is very high). This is true of the castle itself, if for no other reason than that resources are scarce and there are always other concerns competing for them, but also for every component of its defenses: individual towers, gates and walls are not designed to be impenetrable, merely difficult enough.

This is particularly true in castle design because the individuals building these castles often faced fairly sharp limitations in the resources at their disposal. Castles as a style of fortification emerge in a context of political fragmentation, in particular the collapse of the Carolingian Empire, which left even the notional large kingdoms (like the kingdom of France) internally fragmented. Castles were largely being built not by kings but by counts and dukes who held substantial landholdings but nothing like the resources of Charlemagne or Louis the Pious, much less the Romans or Assyrians. Moreover, the long economic and demographic upswing of the Middle Ages was only just beginning to gain momentum; the great cities of the Roman world had shrunk away and the total level of economic production declined, so the sum resources available to these rulers were lower. Finally, the loss of the late Roman bureaucracy (replaced by these fragmented realms running on an economic system best termed “manorialism”) meant that the political authorities (the nobility) often couldn’t even get a hold of a very large portion of the available economic production they did have. Consequently, castle construction is all about producing what security you can with as little labor, money and resources as possible (this is always true of any fortification, mind you, merely that in this period the resource constraints are much tighter).

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part III: Castling”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-10.

December 6, 2023

QotD: What Charles VIII brought back from his Naples vacation

… the basic formula for what would become gunpowder (saltpeter, charcoal, and sulfur in a roughly 75%, 15%, 10% mixture) was clearly in use in China by 1040 when we have our first attested formula, though saltpeter had been being refined and used as an incendiary since at least 808. The first guns appear to be extrapolations from Chinese incendiary “fire lances” (just add rocks!) and the first Chinese cannon appear in 1128. Guns arrive in Europe around 1300; our first representation of a cannon is from 1326, while we hear about them used in sieges beginning in the 1330s; the Mongol conquest and the sudden unification of the Eurasian Steppe probably provided the route for gunpowder and guns to move from China to Europe. Notably, guns seem to have arrived as a complete technology: chemistry, ignition system, tube and projectile.

There was still a long “shaking out” period for the new technology: figuring out how to get enough saltpeter for gunpowder (now that’s a story we’ll come back to some day), how to build a large enough and strong enough metal barrel, and how to actually use the weapons (in sieges? against infantry? big guns? little guns?) and so on. By 1453, the Ottomans have a capable siege-train of gunpowder artillery. Mehmed II (r. 1444-1481) pummeled the walls of Constantinople with some 5,000 shots using some 55,000 pounds of gunpowder; at last Theodosius’ engineers had met their match.

And then, in 1494, Charles VIII invaded Italy – in a dispute over the throne of Naples – with the first proper mobile siege train in Christendom (not in Europe, mind you, because Mehmed had beat our boy Chuck here by a solid four decades). A lot of changes had been happening to make these guns more effective: longer barrels allowed for more power and accuracy, wheeled carriages made them more mobile, trunnions made elevation control easier and some limited degree of caliber standardization reduced windage and simplified supply (though standardization at this point remains quite limited).

The various Italian states, exactly none of whom were excited to see Charles attempting to claim the Kingdom of Naples, could have figured that the many castles and fortified cities of northern Italy were likely to slow Charles down, giving them plenty of time to finish up their own holidays before this obnoxious French tourist showed up. On the 19th of October, 1494, Charles showed up to besiege the fortress at Mordano – a fortress which might well have been expected to hold him up for weeks or even months; on October 20th, 1494, Charles sacked Mordano and massacred the inhabitants, after having blasted a breach with his guns. Florence promptly surrendered and Charles marched to Naples, taking it in 1495 (it surrendered too). Francesco Guicciardini phrased it thusly (trans. via Lee, Waging War, 228),

They [Charles’ artillery] were planted against the Walls of a Town with such speed, the Space between the Shots was so little, and the Balls flew so quick, and were impelled with such Force, that as much Execution was done in a few Hours, as formerly, in Italy, in the like Number of Days.

The impacts of the sudden apparent obsolescence of European castles were considerable. The period from 1450 to 1550 sees a remarkable degree of state-consolidation in Europe (broadly construed) castles, and the power they gave the local nobility to resist the crown, had been one of the drivers of European fragmentation, though we should be careful not to overstate the gunpowder impact here: there are other reasons for a burst of state consolidation at this juncture. Of course that creates a run-away effect of its own, as states that consolidate have the resources to employ larger and more effective siege trains.

Now this strong reaction doesn’t happen everywhere or really anywhere outside of Europe. Part of that has to do with the way that castles were built. Because castles were designed to resist escalade, the walls needed to be built as high as possible, since that was the best way to resist attacks by ladders or towers. But of course, given a fixed amount of building resources, building high also means building thin (and European masonry techniques enabled tall-and-thin construction with walls essentially being constructed with a thick layer of fill material sandwiched between courses of stone). But “tall and thin”, while good against ladders, was a huge liability against cannon.

By contrast, city walls in China were often constructed using a rammed earth core. In essence, earth was piled up in courses and packed very tightly, and then sheathed in stone. This was a labor-intensive building style (but large cities and lots of state capacity meant that labor was available), and it meant the walls had to be made thick in order to be made tall since even rammed earth can only be piled up at an angle substantially less than vertical. But against cannon, the result was walls which were already massively thick, impossible to topple over and the earth-fill, unlike European stone-fill, could absorb some of the energy of the impact without cracking or shattering. Even if the stone shell was broken, the earth wouldn’t tumble out (because it was rammed), but would instead self-seal small gaps. And no attacker could hope that a few lucky hits to the base of a wall built like this would cause it to topple over, given how wide it is at the base. Consequently, European castle walls were vulnerable to cannon in a way that contemporary walls in many other places, such as China, were not. Again, path dependence in fortification matters, because of that antagonistic co-evolution.

In the event, in Italy, Charles’ Italian Vacation started to go badly almost immediately after Naples was taken. A united front against him, the League of Venice, formed in 1495 and fought Charles to a bloody draw at Fornovo in July, 1495. In the long-term, French involvement would draw in the Habsburgs, whose involvement would prevent the French from making permanent gains in a series of wars in Italy lasting well into the 1550s.

But more relevant for our topic was the tremendous shock of that first campaign and the sudden failure of defenses which had long been considered strong. The reader can, I’d argue, detect the continued light tremors of that shock as late as Machiavelli’s The Prince (1532, but perhaps written in some form by 1513). Meanwhile, Italian fortress designers were already at work retrofitting old castles and fortifications (and building new ones) to more effectively resist artillery. Their secret weapon? Geometry.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: Fortification, Part IV: French Guns and Italian Lines”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-12-17.

November 28, 2023

QotD: The tactical problem of attacking WW1 trenches

The trench stalemate is the result of a fairly complicated interaction of weapons which created a novel tactical problem. The key technologies are machine guns, barbed wire and artillery (though as we’ll see, artillery almost ought to be listed here multiple times: the problems are artillery, machine guns, trenches, artillery, barbed wire, artillery, and artillery), but their interaction is not quite straight-forward. The best way to understand the problem is to walk through an idealized, “platonic form” of an attack over no man’s land and the problems it presents.

[…]

So, the first problem: artillery. Neither side starts the war in trenches. Rather the war starts with large armies, consisting mostly of infantry with rifles, backed up by smaller amounts of cavalry for scouting duties (who typically fight dismounted because this is 1914, not 1814) and substantial amounts of artillery, mostly smaller caliber direct-fire1 guns, maneuvering in the open, trying to do fancy things like flanking and enveloping attacks to win by movement rather than by brute attrition (though it is worth noting that this war of maneuver is also the period of the highest casualties on a per-day basis). The tremendous lethality of those weapons – both rifles that are accurate for hundreds of yards, machine guns that can deny entire areas of the battlefield to infantry and the artillery, which is utterly murderous against any infantry it can see and by far the most lethal part of the equation – all of that demands trenches. Trenches shield the infantry from all of that firepower. So you end up with parallel trenches, typically a few hundred yards apart as the armies settle in to defenses and maneuver breaks down (because the armies are large enough to occupy the entire front from the Alps to the Sea).

The new problem this creates, from the perspective of the defender, is how to defend these trenches. If enemies actually get close to them, they are very vulnerable because the soldier at the top of the trench has a huge advantage against enemies in the trench: he can fire down more easily, can throw grenades down very easily and also has an enormous mechanical advantage if the fight comes to bayonets and trench-knives, which it might. If you end up fighting at the lip of your trench against massed enemy infantry, you have almost certainly already lost. The defensive solution here, of course, are those machine guns which can deploy enough fire to prohibit enemies moving over no man’s land: put a bunch of those in strong-points in your trench line and you can prevent enemy infantry from reaching you.

Now the attacker has the problem: how to prevent the machine guns from making approach impossible. The popular conception here is that WWI generals didn’t “figure out” machine guns for a long time; that’s not quite true. By the end of 1914, most everyone seems to have recognized that attacking into machine guns without some way of shutting them down was futile. But generals who had done their studies already had the ready solution: the way to beat infantry defenses was with artillery and had been for centuries. Light, smaller, direct-fire guns wouldn’t work2 but heavy, indirect-fire howitzers could! Now landing a shell directly in a trench was hard and trenches were already being zig-zagged to prevent shell fragments flying down the whole line anyway, so actually annihilating the defenses wasn’t quite in the cards (though heavy shells designed to penetrate the ground with large high-explosive payloads could heave a hundred meters of trench along with all of their inhabitants up into the air at a stretch with predictably fatal results). But anyone fool enough to be standing out during a barrage would be killed, so your artillery could force enemy gunners to hide in deep dugouts designed to resist artillery. Machine gunners hiding in deep dugouts can’t fire their machine guns at your approaching infantry.

And now we have the “race to the parapet”. The attacker opens with a barrage, which has two purposes: silence enemy artillery (which could utterly ruin the attack if it isn’t knocked out) and second to disable the machine guns: knock out some directly, force the crews of the rest to flee underground. But attacking infantry can’t occupy a position its own artillery is shelling, so there is some gap between when the shells stop and when the attack arrives. In that gap, the defender is going to rush to set up their machine guns while the attacker rushes to get to the lip of the trench:first one to get into position is going to inflict a terrible slaughter on the other.

Now the defender begins to look for ways to slant the race to his advantage. One option is better dugouts and indeed there is fairly rapid development in sophistication here, with artillery-resistant shelters dug many meters underground, often reinforced with lots of concrete. Artillery which could have torn apart the long-prepared expensive fortresses of a few decades earlier struggle to actually kill all of the infantry in such positions (though they can bury them alive and men hiding in a dugout are, of course, not at the parapet ready to fire). The other option was to slow the enemy advance and here came barbed wire. One misconception to clear up here: the barbed wire here is not like you would see on a fence (like an animal pen, or as an anti-climb device at the top of a chain link fence), it is not a single wire or a set of parallel wires. Rather it is set out in giant coils, like massive hay-bales of barbed wire, or else strung in large numbers of interwoven strands held up with wooden or metal posts. And there isn’t merely one line of it, but multiple lines deep. If the attacker goes in with no preparation, the result will be sadly predictable even without machine guns: troops will get stuck at the wire (or worse yet, on the wire) and then get shot to pieces. But even if troops have wire-cutters, cutting the wire and clearing passages through it will still slow them down … and this is a race.

Bret Devereaux, “Collections: No Man’s Land, Part I: The Trench Stalemate”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2021-09-17.

1. Direct fire here means the guns fire on a low trajectory; you are more or less pointing them where you want the shell to go and shooting straight at it, as you might with a traditional firearm.

2. The problem with direct-fire artillery here is that you cannot effectively hide it in a trench (because it’s direct fire) and you can’t keep it well concealed, so in the event of an attack, the enemy is likely to begin by using their artillery to disable your artillery. The limitations of direct-fire guns hit the French particularly hard once the trench stalemate set in, because it reduced the usefulness of their very effective 75mm field gun (the famed “French 75” after which the modern cocktail is named [Forgotten Weapons did a video covering both]). That didn’t make direct-fire guns useless, but it put a lot more importance on much heavier indirect-fire artillery.