The history of “education”, of the university system, whatever you want to call it, is long and complicated and fascinating, but not really germane. Like all human institutions, “educational” ones grew organically around what were originally very different foundations, the way coral reefs form around shipwrecks. Oversimplifying for clarity: back in the day, “schools” were supposed to handle education […] while universities were for training. That being the case, very few who attended universities emerged with degrees — a man got what training he needed for his future career, and unless that future career was “senior churchman”, the full Bachelor of Arts route was pretty much pointless.

(At the risk of straying too far afield, let’s briefly note that “senior churchman” was a common, indeed almost traditional, career path for the spare sons of the aristocracy. Well into the 18th century, every titled parent’s goal was “an heir and a spare”, with the heir destined for the title and castle and the spare earmarked for the church … but not, of course, as some humble parish priest. It was pretty common for bishops or abbots, and sometimes even cardinals, to be ordained on the day they took over their bishoprics. See, for example, Cesare Borgia. Meanwhile the illiterate, superstitious, brutish parish priest was a figure of satire throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance. A guy like Thomas Wolsey was hated, in no small part, precisely because he was a commoner who leveraged his formal education into a senior church gig, taking a bunch of plum positions away from the aristocracy’s spare sons in the process).

That being the case — that schools were for education, universities for training — the fascinating spectacle of some 18 year old fop fresh out of Eton being sent to govern the Punjab makes a lot more sense. His character, formed by his education (in our sense), was considered sufficient; he’d pick up such technical training as he needed on the job … or employ trained technicians to do it for him. So too, of course, with the army, and the more you know about the British Army before the 20th century, the more you’re amazed that they managed to win anything, much less an empire — the heir’s spare’s spare traditionally went into the army, buying his commission outright, which meant that quite senior commands could, and often did, go to snotnosed teenagers who didn’t know their left flank from their right.

Alas, governments back in the days were severely under-bureaucratized, meaning that the aristocracy lacked sufficient spares to fill all the technician roles the heirs required in a rapidly urbanizing, globalizing world… which meant that talented commoners had to be employed to fill the gaps. See e.g. Wolsey, above. The problem with that, though, is that you can’t have some dirty-arsed commoner, however skilled, wiping his nose on his sleeve while in the presence of His Lordship, so universities took on a socializing function. And so (again, grossly oversimplifying for clarity) the “bachelor of arts” was born, meaning “a technician with the social savvy to work closely with his betters”. A good example is Thomas Hobbes, whose official job title in the Earl of Devonshire’s household was “tutor”, but whose function was basically “intellectual technician” — he was a kind of man-of-all-work for anything white collar …

At that point, if there had been a “system” of any kind, what the system’s designers should’ve done is set up finishing schools. The “universities” of Oxford, Cambridge, etc. are made up of various “colleges” anyway, each with their own rules and traditions and house colors and all that Harry Potter shit. Their Lordships should’ve gotten together and endowed another college for the sole purpose of knocking manners into ambitious commoners on the make (Wolsey might actually have had something like this in mind with Cardinal College … alas).

But they didn’t, and so the professors at the traditional colleges were forced into a role for which they were not designed, and unqualified. That tends to happen a lot — have you noticed? It actually happened to them twice, once with the need for technicians-with-manners became apparent, and then again when the realization dawned — as it did by the 1700s, if not earlier — that some subjects, like chemistry, require not just technicians and technician-trainers, but researchers. Hard to blame the “system” for this, since of course there is no “system”, but also because such a thing would be ruinously expensive.

Hence by the time an actual system came into being — in Prussia, around 1800 — the professors awkwardly inhabited the three roles we started with. The Professor of Chemistry, say, was supposed to conduct research while training technicians-with-manners. As with the pre-machinegun British army, the astounding thing is that they managed to pull it off at all, much less to such consistently high quality. They were real men back then …

Severian, “Education Reform”, Rotten Chestnuts, 2020-11-17.

August 8, 2023

QotD: The British imperial educational “system”

May 1, 2023

Britain’s first embassy to India

In The Critic, C.C. Corn reviews Courting India: England, Mughal India and the Origins of Empire by Nandini Das, a look at the first, halting steps of the East India Company at the court of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir early in the seventeenth century:

The late Sir Christopher Meyer, the closest thing modern British diplomacy has produced to a public figure, enjoyed comparing his trade to prostitution. Both are ancient trades, and neither enjoys a wholly favourable reputation. Any modern diplomat will discreetly confirm that the profession is far from the anodyne, flag-emoji civility and coyly embarrassed glamour they project on Twitter.

Whilst none of our modern representatives are working in quite the same conditions as their predecessor Sir Thomas Roe, they may well find uncanny parallels with his unfortunate mission.

The fledgling and precarious East India Company, founded in 1600, had sent representatives to the Mughal court before, but they were mere merchants and messengers. The stern rebuff they received called for a formal representative of the King.

After the company persuaded James I of the necessity, Thomas Roe (a well-connected MP, friend to John Donne and Ben Jonson, and already an experienced traveller after an attempt to reach the legendary El Dorado) was dispatched to the court of Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1615. He remained there until 1619, in an embassy that the cultural historian, Nandini Das, describes in Courting India as “infuriatingly unproductive”.

The company kept rigorous records, and Roe meticulously kept a daily diary. Professor Das uses these and the reports of other English travellers to narrate Roe’s journey, as well as contemporary literature and, more importantly, their Indian equivalents. It is not so much the diplomatic success that fascinates Das about Roe’s embassy, but the mindset of the early modern encounter between England and India.

In a boom time for histories of British colonialism, this is an intelligent and gripping book with a thoughtful awareness of human relationships and frailties, and a model approach to early modern cross-cultural encounters.

The privations suffered by Roe’s embassy are striking. Only three in ten people had a chance of coming home alive from the voyage to India. Das’s recreation of the journey out is as intense and claustrophobic as Das Boot, with rotten medicine, cruel maritime punishments and untrained boys acting as surgeons. Dead bodies onboard would have their toes gnawed off by rats within hours.

In India, the English sailors excelled themselves as uncouth Brits abroad: drinking, fighting and baiting local customs, such as killing a calf. A chaplain was notorious for “drunkenly dodging brothel-keepers and engaging in half-naked brawls”. For most of his time, Roe — seeking to keep costs down — lived with merchants and factors already in India, in a cramped, filthy, dangerous house.

April 30, 2023

David Howarth’s history of the East India Company

Robert Lyman reviews David Howarth’s recent work Adventurers: The Improbable Rise of the East India Company:

It is the human detail of the EIC and the ultimate triumph of its trading endeavours despite the best efforts of Portugal, the Dutch Republic and of the vicissitudes of Neptune that holds great fascination for me, and which is the triumph of Howarth’s intimate and intricate portrayal of the EIC in the first century of its existence. His great achievement is both to bring the dusty tomes of the Company back to life, not just to humanise one of the greatest trading ventures of all of human history, but to interpret the early years of the Company (his book spans 1600 to 1688, though most of the narrative is pre-1650) as a peculiarly human rather than an institutional endeavour. Is this important? Yes. Humans have agency; institutions consume or act upon the determining agency of human beings, not the other way around. Too much of modern (post 1880) history is based upon determining the perspective of organisations and movements (as interpreted by later historians, many with their own ideological baggage) rather than of actual, real live people making decisions for themselves in the peculiar and particular context of their lives and times.

The means through which Howarth paints his story is by the decisions, actions and activities of actual people, some influential decision-makers and many others who were not, all of which makes up a remarkably vivid tapestry of human intercourse. Each chapter, for instance, is constructed around a person or group of people. One powerfully tells the story of the men of the Peppercorn, an EIC East Indiaman, as it seeks out the riches of a world on the extreme periphery of the consciousness of most Europeans. The ultimate triumph of European expansion into Asia is not difficult to comprehend. Europe was pursuing an adventure, aggressively, relentlessly and determinedly, to bring the riches of the world back to its own shores. At no time did the Chinese, Japanese, Indians or inhabitants of the Spice Islands return the favour. The energetic persistence of Sir Thomas Roe, for instance, the Company’s ambassador to the Mughal court (1615-1619), is easily compared to the intellectual (and alcoholic) indolence of the Great Mughal with whom Roe was attempting to interact. Roe was there, in India: Europeans were interested in the “East” and with travelling to the other side of the world for purposes of human engagement, adventure, patriotism and, yes, greed and selfish self-interest. The Great Mughal, by contrast, was also driven by greed and self-interest, but he just wasn’t interested in exploring. He certainly wasn’t interested in Europe. He was already, in his view, at the top of the human tree and had no need for either the ideas or the money of the red-haired barbarians who came from across the sea, a sea that incidentally few Mughal emperors had (amazingly) ever even seen. Fascinatingly, the Mughal shared with King James I an abhorrence with “trade”, though James knew he needed grubby merchants like Sir John Lyman [the reviewer’s ancestor] as they gave him coin. It wasn’t just about the merchants: Kings and governments needed the money that the merchants delivered by the bucket load because they couldn’t create it themselves. Howarth astutely observes that the “EIC belonged to the globe of politics as much as it did to the sphere of commerce”. Indeed, something of a symbiosis between the two in Tudor and Stewart England created a sense of nationhood – in the face of the resistance of others, in Europe and further afield – for the first time. The Mughal Empire was ultimately swallowed up as a result of a dynamism by European politicians and merchants working in unison which it never bothered to replicate by undergoing the reverse journey.

And power? No. Howarth is remarkably clear that the primary task of the EIC was to make money, not to accrue territory, create power in foreign territories or aggrandise native populations. The role of the executive arm of the EIC (its ships, sailors and factors) was to make money for its investors, many of whom were the very merchant adventurers in the little ships travelling east over vast oceans. The great game of mercantile expansion took place because those who had most to lose were also sailing the ships, negotiating with foreign emissaries, fighting the Portuguese and the Dutch and placing their lives on the line. Amazingly, in 1570 England had only 58,000 tons of marine tonnage compared with Spain’s 300,000, and was very definitely the minnow in the rush to conquer the seas. The men who built and sailed its boats came from a long way behind, and yet in time were to build a seagoing commercial empire which more than rivalled all its competition. Its early growth was fuelled by the wealth provided by spice rather than slaves and, in contradistinction to what some modern historical moralists are keen to tell us, by a “reluctance to use violence and vigilance to avoid land commitments”. Indeed, unlike that of the Dutch, and despite what one might assume if we were to read the British national anthem back into history, “expansion in England happened with no appeal whatever to national glory”.

The amazing thing about the EIC was just how chaotic and disorganised it was. There was nothing inevitable about its rise as a monolithic mercantile overlord destined for instance, in the due course of time, to rule India. Second guessing history is only possible for historians able to look backwards and identify trends and features, convictions that didn’t exist for those when history was happening trying to make their way through the fog of an uncertain and troublesome future. The EIC proved simply to be better organised than the Portuguese, and not distracted as the Dutch were in their long war against Spain. Luck and serendipity played as much a role on the eventual survival of the EIC as did its ability to raise massive amounts of money from venturers in England (every raise or round of financing was heavily over-subscribed) for its adventures and to recruit adventurers to take its ships to sea. The EIC was phenomenally successful in raising voluntary capital to fund its ventures relative to other European states. By comparison, “although Iberian barns might have looked well built and better stocked, once they were given a good kick the rusted hinges flew off”.

April 22, 2023

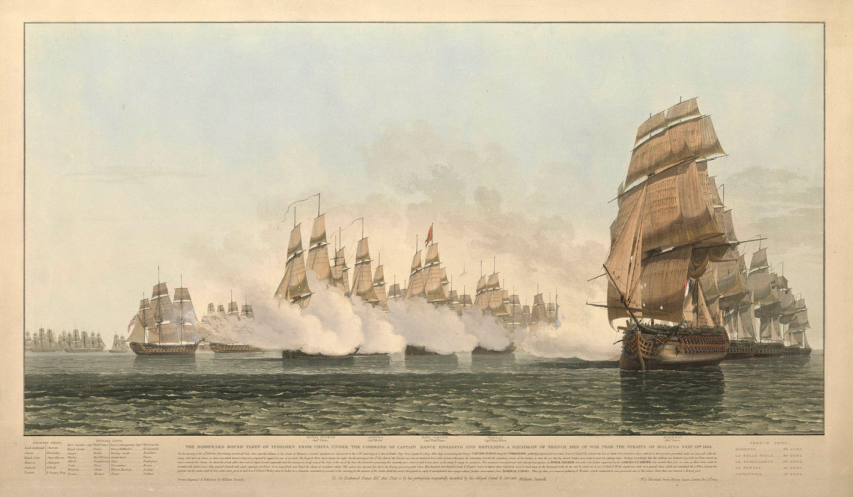

The action off Pula Aura, February 1804

Ned Donovan recounts a very dangerous moment for the British East India Company — and the larger British economy — as a French naval squadron threatened the EIC’s China Fleet carrying a cargo that would be the rough equivalent of £750 million in today’s money:

It will not be surprising to any reader that the East India Company was arrogant. A company that, as William Dalrymple describes, had become “an empire within an empire”. It controlled much of India, had its own army, and its revenues kept Britain afloat. Its navy was also not to be sniffed at, made up of large, well-built ships (known as Indiamen) capable of being as armed as any British warship, but its commercial arrogance prevented this. Rather than fill these Indiamen with cannons and the hundreds of sailors needed to man them, it instead filled its gun ports with dummy cannons and its decks with luxurious cabins and storage for trade goods, maintaining crews only large enough to sail these ships and be stewards to its paying passengers.

Commodore Dance would have been pondering those dummy cannons as the ships he had sent to look at the four strange sail in the southwest reported back that it was four French warships, Linois’s squadron. He was practically defenceless. To protect his 30 ships and their precious cargo, he had one small armed brig named the Ganges with around a dozen guns. Up against him were the 186 guns of the French squadron, 74 in Marengo, 40 in Belle Poule, 36 in Semillante, 20 in Berceau and 16 in Aventurier. As Dance watched through his telescope, the French ships hoisted their colours, and the admiral’s flag of Linois broke out above Marengo. He needed a plan. Fast.

After a night of cat and mouse between the French and British, Dance ordered his convoy into a long single line and at the front put four of the largest Indiamen – the Royal George, Earl Camden, Warley, and Alfred. He then commanded that these four hoist blue ensigns, the sign of Royal Navy ships. This wasn’t the most absurd plan; the East India Company, in their arrogance, had a policy of painting their Indiamen to look like Royal Navy ships – as Dance records in his despatch: “We hoisted our colours and offered him battle.” But Linois and his ships continued to approach the convoy slowly, with Dance realising that the French intended to separate the convoy and take it apart piece by piece. It was now or never, and Dance took the initiative. At 1 pm, he ordered the Ganges, Royal George, Earl Camden, Warley and Alfred to turn and intercept the French. All the ships turned perfectly and crossed Linois, and at 1:15 pm, the French opened fire on the Royal George. In the preceding night, the convoy had put all the guns they had on these five ships and filled them with as many brave volunteers as they could. All five returned fire on the French warships, and one sailor on the Royal George was killed. I will let Dance take over here:

“But before any other ship could get into action, the enemy hauled their wind and stood away to the east under all the sail they could set. At 2 pm, I made the signal for a general chase and we pursued them until 4 pm.”

In around 40 minutes, Dance and his handful of real guns and dummy cannons had forced the French warships to withdraw under the belief it had engaged an elite squadron of Royal Navy ships. Not content with this victory, he then ordered his ships to chase the French down and stop them from returning. By the later afternoon, it was clear Linois had run, and Dance ordered his convoy to regroup and make for the safety of Malacca.

In the Straits of Malacca, Dance met the ships the Royal Navy had sent to escort him on the outbreak of war but would have been too late had the commodore not thought fast. The China Fleet passed the rest of its voyage without incident, returning to Britain in the summer of 1804.

To say the country was ecstatic would be an understatement. If the China Fleet and its £8 million had been taken, as Linois would have been perfectly able to do, it is evident that both the East India Company and Lloyds of London would have faced bankruptcy and collapse. Nathaniel Dance was knighted by George III and given a fantastic sword by Lloyds worth 100 guineas. With the sword came £5,000 (£403,000 today) from the Bombay Insurance Company and £500 a year (£40,000 today) from the East India Company, along with a share in the £50,000 given to all who sailed in convoy. Sir Nathaniel retired immediately and never took to the sea again, dying peacefully in 1827.

Poor Admiral Linois, on the other hand, never lived down the fracas, with Napoleon writing after the event, “[Linois] has shown want of courage of mind, that kind of courage which I consider the highest quality in a leader”. Despite that, Linois remained in the French navy … only to once again run into the fickleness of fate:

It is worth remarking that following the defeat at Pulo Aura, Linois had a similarly pathetic rest of the war that ended in a wonderfully ironic way. In 1806, the admiral was captured when he mistook a British squadron of warships for a merchant convoy.

Irony? That’s cosmic level stuff.

March 4, 2023

Nigel Biggar’s Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning

In The Critic, Robert Lyman reviews a recent book offering a rather more nuanced view of the British empire:

The book is a careful analysis of empire from an ethical perspective, examining a set of moral questions. This includes whether the British Empire was driven by lust or greed; whether it was racist and condoned, supported or encouraged slavery; whether it was based on the conquest of land; whether it entailed genocide and or economic exploitation; whether its lack of democracy made it illegitimate; and whether it was intrinsically or systemically violent.

Biggar’s proposition is simple: that we look at Britain’s history without assuming the zero-sum position that imperialism and colonialism were inherently bad, that motives and agency need to be considered and that good did flow from bad, as well as bad from good.

Whether he succeeds depends on the reader’s willingness to appreciate these moral or ethical propositions, and to re-evaluate accordingly. In my view, he has mounted a coolly dispassionate defence of his proposition, challenging the hysteria of those who suggest that the British Empire was the apotheosis of evil. Biggar’s calm dissection of these inflated claims allows us to see that they say much more about the motivations, assumptions and political ideologies of those who hold these views than they do about what history presents to us as the realities of a morally imperfect past.

He reminds us that British imperialism had no single wellspring. Most of us can easily dismiss the notion that it was a product of an aggressive, buccaneering state keen to enrich itself at the expense of peoples less able to defend themselves. Equally, it is untrue that economic motives drove all imperialist or colonial endeavour, or that economics (business, trade and commerce) was the primary force sustaining the colonial regimes that followed.

As Biggar asserts, both imperialism and colonialism were driven from different motivations at different times. Each ran different journeys, with different outcomes depending on circumstances. The assertion that there is a single defining imperative for each instance of imperial initiative or colonial endeavour simply does not accord with the facts.

Whilst other issues played a part, it was social, religious and political motives which drove the colonial endeavour in the New World from the 1620s: security and religion drove the subjugation of Catholic (and therefore Royalist) Ireland in the 1650s; social and administrative factors led to the settlement in Australia from 1788; and social and religious imperatives drove the colonisation of New Zealand in the 1840s.

In circumstances where trade and the security of trade was the primary motive for imperialism — think of Clive in the 1750s, for example — a wide variety of outcomes ensued. Some occurred as a natural consequence of imperialism. In India, Clive’s defeat of the Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah in 1757 was in support of a palace coup that put Siraj’s uncle Mir Jafar on the throne of Bengal, thus allowing the East India Company the favoured trading status that Siraj had previously rejected.

This led in time to the Company taking over the administrative functions of the Bengal state (zamindars collected both rents for themselves and taxes for the government). Seeking to protect its new prerogatives, it provided security from both internal (civil disorder and lawlessness) and external threats (the Mahratta raiders, for example). The incremental, almost accidental, accrual of power that began in the early 1600s stepped into colonial administration 150 years later, leading to the transfer of power across a swathe of the sub-continent to the British Crown in 1858.

Biggar’s argument is that, running in parallel with this expansion came a host of other consequences, not all of which can be judged “bad”. We may not like what prompted the colonial enterprise at the outset (not all of which was morally contentious, such as the need to trade), but we cannot deny that good things, as well as bad, followed thereafter.

March 6, 2022

Lugers for the Dutch East Indies Army

Forgotten Weapons

Published 3 Nov 2021http://www.patreon.com/ForgottenWeapons

https://www.floatplane.com/channel/Fo…

Cool Forgotten Weapons merch! http://shop.forgottenweapons.com

Note: When I say the double magazine pouch is unique for this model, I was not thinking about those issued with LP-08 Artillery Lugers.

While the Dutch Army dithered over new pistol adoption, the Dutch East Indies Army (KNIL) took more decisive action and adopted the Luger as the M11 in 1911 after a few years of testing. They ordered the first batch of 4,181 from DWM in the years before World War One. After the Treaty of Versailles, German companies were barred from military production, and so the KNIL bought a batch of 6,000 Lugers from the Vickers company in the UK. These were still insufficient for the force, and in 1928 they ordered one final batch of guns.

This final batch was made by DWM. The Allied Control Commission ceased operation in 1927 and left Germany, and DWM almost immediately resumer Luger production. This final batch consisted of 3,828 more M11 pattern pistols. All three batches were in a single serial number range, starting at 1 and running to 14020. They were chambered for the 9x19mm Parabellum cartridge, with 4 inch (100mm) barrels. Unit marks were engraved originally on the back of the frame, but in 1919 this was replaced with the use of a small brass plaque on the trigger guard. A plaque on the left side of the frame was introduced for unit marks in 1939, as seen on this example.

We also have an original KNIL M11 holster and double magazine pouch to take a look at — accessories that are extremely rare today.

Contact:

Forgotten Weapons

6281 N. Oracle 36270

Tucson, AZ 85740

February 8, 2022

QotD: The East India Company’s rise to power

We still talk about the British conquering India, but that phrase disguises a more sinister reality. It was not the British government that seized India at the end of the 18th century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London, and managed in India by an unstable sociopath – Clive.

In many ways the EIC was a model of corporate efficiency: 100 years into its history, it had only 35 permanent employees in its head office. Nevertheless, that skeleton staff executed a corporate coup unparalleled in history: the military conquest, subjugation and plunder of vast tracts of southern Asia. It almost certainly remains the supreme act of corporate violence in world history. For all the power wielded today by the world’s largest corporations – whether ExxonMobil, Walmart or Google – they are tame beasts compared with the ravaging territorial appetites of the militarised East India Company. Yet if history shows anything, it is that in the intimate dance between the power of the state and that of the corporation, while the latter can be regulated, it will use all the resources in its power to resist.

When it suited, the EIC made much of its legal separation from the government. It argued forcefully, and successfully, that the document signed by Shah Alam – known as the Diwani – was the legal property of the company, not the Crown, even though the government had spent a massive sum on naval and military operations protecting the EIC’s Indian acquisitions. But the MPs who voted to uphold this legal distinction were not exactly neutral: nearly a quarter of them held company stock, which would have plummeted in value had the Crown taken over. For the same reason, the need to protect the company from foreign competition became a major aim of British foreign policy.

The transaction depicted in the painting [Wiki] was to have catastrophic consequences. As with all such corporations, then as now, the EIC was answerable only to its shareholders. With no stake in the just governance of the region, or its long-term wellbeing, the company’s rule quickly turned into the straightforward pillage of Bengal, and the rapid transfer westwards of its wealth.

Before long the province, already devastated by war, was struck down by the famine of 1769, then further ruined by high taxation. Company tax collectors were guilty of what today would be described as human rights violations. A senior official of the old Mughal regime in Bengal wrote in his diaries: “Indians were tortured to disclose their treasure; cities, towns and villages ransacked; jaghires and provinces purloined: these were the ‘delights’ and ‘religions’ of the directors and their servants.”

Bengal’s wealth rapidly drained into Britain, while its prosperous weavers and artisans were coerced “like so many slaves” by their new masters, and its markets flooded with British products. A proportion of the loot of Bengal went directly into Clive’s pocket. He returned to Britain with a personal fortune – then valued at £234,000 – that made him the richest self-made man in Europe. After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, a victory that owed more to treachery, forged contracts, bankers and bribes than military prowess, he transferred to the EIC treasury no less than £2.5m seized from the defeated rulers of Bengal – in today’s currency, around £23m for Clive and £250m for the company.

William Dalrymple, “The East India Company: The original corporate raiders”, Guardian, 2015-03-04.

January 22, 2022

1842 Retreat From Kabul

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 22 Sep 2021On January 13, 1842, a single man on horseback approached the British garrison at Jalalabad, where soldiers were waiting for a retreating army of several thousand. Exhausted, the man had part of his skull shaved off by a sword and his horse was so exhausted that it would soon perish. As he was brought into the walls of the city the lone man was asked where the rest of the army was. “I am the army,” he replied. Thus ended a disastrous retreat from Kabul, where a British force of some 4,500 soldiers and thousands of civilians was almost entirely destroyed.

This is original content based on research by The History Guy. Images in the Public Domain are carefully selected and provide illustration. As very few images of the actual event are available in the Public Domain, images of similar objects and events are used for illustration.

You can purchase the bow tie worn in this episode at The Tie Bar:

https://www.thetiebar.com/?utm_campai…All events are portrayed in historical context and for educational purposes. No images or content are primarily intended to shock and disgust. Those who do not learn from history are doomed to repeat it. Non censuram.

Find The History Guy at:

Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/TheHistoryGuy

Please send suggestions for future episodes: Suggestions@TheHistoryGuy.netThe History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered is the place to find short snippets of forgotten history from five to fifteen minutes long. If you like history too, this is the channel for you.

Awesome The History Guy merchandise is available at:

https://teespring.com/stores/the-hist…Script by JCG

#history #thehistoryguy #Afghanistan

October 11, 2021

The Darien Venture: The Colony that Bankrupted Scotland

Geographics

Published 14 Nov 2019If a Nation’s wealth and power were to be measured in stubbornness, resilience, and inventiveness, rather than GDP, Scotland would be a top-5 superpower. The people that brought to you televisions, refrigerators, penicillin, and gin & tonic have gone through many a rough patch throughout their history. Very often, hard times were related to their rocky relationship with their Southern neighbours, the English.

Credits:

Host – Simon Whistler

Author – Arnaldo Teodorani

Producer – Jennifer Da Silva

Executive Producer – Shell HarrisBusiness inquiries to admin@toptenz.net

September 13, 2021

How Is Worcestershire Sauce Made? | How Do They Do It?

DCODE by Discovery

Published 25 Sep 2018Worcestershire Sauce was invented in 1835 when a posh army officer went to India to help run the British Empire. He fell in love, not with a woman, but with a fish sauce. DCODE how the iconic sauce is made in England today.

#DCODE, #HowDoTheyDoIt, #WorcestershireSauce

September 12, 2021

Ocean travel without losing half the crew to scurvy

In the most recent Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes discusses the scurvy dogs of the Spanish Main, or any other ocean before Europeans discovered how to fight off scurvy:

An English ship of the late 16th/early 17th century: this is a replica of the Susan Constant at the Jamestown Settlement in Virginia. The original ship was built sometime before 1607 and rented by the Virginia Company of London to transport the original settlers to Jamestown.

Photo by Nicholas Russon, March 2004.

For as long as humans have suffered severe food shortages, scurvy has been known. The first record of it appears to date to ancient Egypt, in 1550BC, and it was especially familiar to the inhabitants of northern climates, with fresh vegetation every winter becoming scarce. Our word for scurvy almost certainly comes from the old Norse skyrbjugr — the skyr being a sort of soured cow’s milk that was thought to have caused the disease by going bad. In mid-sixteenth-century sources, scurvy was often referred to as though it was endemic to the Netherlands — a flat land assailed by the North Sea each winter, that had suffered long sieges and devastation thanks to the Dutch Revolt, and where fishing and merchant shipping employed an especially large proportion of the workforce. The Dutch thus had a perfect storm of factors to make vitamin C deficiencies more common, even though they abounded in fresh-caught fish and imported Baltic grain.

And so, over the centuries, the people of the northern climes had discovered the cure. Or rather, cures. The Iroquois ate the bark, needles or sap of evergreen trees — most likely white cedar, or some other kind of spruce, fir, juniper or pine, all rich in vitamin C. Their remedy saved the lives of Jacques Cartier’s colonists based near modern-day Quebec City in the winter of 1536. It’s the reason white cedar is known as arborvitae, the tree of life. And the Saami of northern Scandinavia prized cabbages and other leafy greens, in the summertime filling up casks of reindeer milk with crowberries and cloudberries, to be ready for winter.

[…]

Still more remedies were discovered by accident, as European ships began to range farther and farther abroad. The very first Portuguese voyagers around the Cape of Good Hope almost immediately discovered the value of orange and lemons — especially effective sources of vitamin C, as their acidity helps to preserve it. The voyage of Vasco da Gama, having been the first to round the Cape and reach the eastern coast of Africa, was then stricken with scurvy. They were only inadvertently saved when they traded with some Arabian ships laden with oranges, before landing at Mombasa. There, the ruler sent them a sheep and some sugar-cane, the gift also happening to include some oranges and lemons. Although the Portuguese couldn’t stay there long — they learned of a conspiracy to capture their ship — one of the voyagers later reported in wonder how the climate there must have been especially healthful to have cured them all.

Fortunately, at least some of the crew suspected the citrus instead. On the return journey from India, after a fatally slow three-month crossing of the Indian Ocean, some of the newly scurvy-ridden sailors asked their captain to procure them some oranges at Malindi. At least a few of the crew must certainly have been saved by this request, though perhaps the excitement of their imminent deliverance induced a few fatal aneurysms: “our sick did not profit”, was the report, “for the climate affected them in such a way that many of them died here.” By the time the fleet limped home back to Lisbon in 1499, scurvy had still managed to claim the lives of over two thirds of the original crew.

Nonetheless, the status of oranges as a scurvy wonder-cure had entered sailors’ lore. When Pedro Alvares Cabral repeated da Gama’s feat of rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1500, his crew purposefully treated their scurvy using oranges. And by the 1560s, if not earlier, the news of the cure had spread beyond the Portuguese. Sailors from the Low Countries, on the eve of the Dutch Revolt from Spain, were said to be staving off scurvy by eating oranges in large quantities, skins and all. (Orange peel is in fact especially rich in vitamin C, so they were onto something.) Their value was certainly appreciated by the Dutch explorer Jacob Corneliszoon van Neck by the time of his second expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1598. Not long after setting out, he purchased 10,000 oranges from a passing ship off the coast of Spain, rationing them out to all his crew. And on the return journey via St Helena they were dismayed when initially “we found no oranges, whereof we had most need, for those that were troubled with the scurvy disease.”

The account of van Neck’s journey was translated into English for the first voyage of the East India Company in 1601, which may be why its commander, James Lancaster, directed his crew to drink three spoonfuls of lemon juice every morning. Lancaster doesn’t appear to have paid any special attention to oranges and lemons ten years earlier, when he first attempted the voyage, although other English mariners like the privateer Sir Richard Hawkins had in the 1590s already been extolling their virtues. We don’t know many of the details of Lancaster’s lemon juice trial, but his flagship’s crew was not entirely saved. Contrary to common report, at least a third of them had died by the time they left their first landing at Table Bay, South Africa — a proportion similar those on the other ships of his fleet, though we don’t know how many actually died of scurvy or of other causes. But upon the expedition’s return, the experience placed lemon juice firmly on the list of known scurvy cures — “the most precious help that ever was discovered against the scurvy” as the East India Company’s surgeon-general put it.

September 4, 2021

Recreating the original India Pale Ale

In The Critic, Henry Jeffreys discusses the rebirth of the original IPA:

From an early age Jamie Allsopp had wanted to bring back the beer that made his family name. It was his ancestor Samuel Allsopp who made the very first Burton IPA, and created a style that is now a global phenomenon. Hell, there are even brewers in Germany making IPA these days.

Though IPA is most associated with Burton-on-Trent, it was originally brewed in London by Hodgson’s, the nearest brewery to East India Dock. Here East India Company servants would buy beer to sell at a vast profit in India. The beer of choice was a strong, heavily-hopped ale designed to last through the winter months. On the six-month voyage through the tropics, it was found to have matured splendidly, rather like wine from Madeira did. Shipped in the early-nineteenth century, this was the first India Pale Ale, though it wasn’t known as such.

Frederick Hodgson then got greedy and tried to cut out the East India Company by shipping directly. So, Campbell Majoribanks, a director at the Company, approached Burton brewer Samuel Allsopp to make a rival beer. Allsopp brewed a sample in a teapot which met with approval and the beer was shipped to India from 1823.

Burton-on-Trent had an advantage over London in that the water contained gypsum, calcium sulphate, which made the beer brighter and clearer with a pronounced acidic bite. It suited a pale crisp beer, made possible by the recent invention of pale malt, very different to the heavy dark porter that London was famed for.

Other Burton brewers such as Bass & Ratcliff got in on the act. This new beer wasn’t just a hit in India; it became all the rage back in Britain. Railways meant that Burton beer could be sent to London cheaply, and the porter that had dominated the capital began to die out, displaced by this new refreshing beer. Some time in the 1830s the name IPA began to be used.

It was the drink of the aspirant middle class. It would have sold for twice as much as ordinary beer. So popular were Burton beers that by 1877 the Bass brewery was the largest in the world. Bass had the red triangle trademark whereas Allsopp’s symbol was the red hand.

The Allsopp family, like many of the great brewing families, moved into politics. Samuel’s son Henry was elevated to the peerage as 1st Baron Hindlip. In fact, so great was the political influence of brewing families that they were known as “the beerage”. Gladstone attributed the liberal defeat in the 1874 election to this powerful faction: “We have been borne down in a torrent of gin and beer”, he wrote.

But the Allsopp’s brewing heyday did not last long. According to Jamie Allsopp, in 1897, the family “built a big lager brewery and nobody wanted lager and it finished the company”. They were pushed out in 1911 when the firm went into receivership. It soldiered on before merging with another Burton brewer, Ind Coope, in 1934. Following waves of mergers and acquisitions, the name and the famous red hand disappeared in 1959.

August 29, 2021

The competing English and Dutch East India companies

In his latest Age of Invention newsletter, Anton Howes considers the odd fact that although the Dutch were the last major seafaring power to extend to the East Indies, they quickly became the most powerful European traders and colonialists in the region:

By the mid-seventeenth century, although the trans-Atlantic trades were still almost entirely in the hands of the Spanish, the European trade to the Indian Ocean had come to be dominated by the Dutch — which is quite surprising, as they had arrived so late. The high-value exports of the Indian Ocean — particularly pepper — had anciently arrived via the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf, or overland, and then been bought up in Egypt or Syria by the Venetians and Genoese, who then sold them on to the rest of Europe. It was then the Portuguese who had supplanted that trade in the late fifteenth century by discovering the direct route to the Indian Ocean around the Cape of Good Hope. The Portuguese monopolised the new sea route around Africa for a century, almost totally undisturbed by other Europeans, entrenching their position by building forts — occasionally with the permission of local rulers, but often without.

The Portuguese seem to have spread the rumour in Europe that they had effectively conquered the entire region, presumably to dissuade others from even trying to break their monopoly. Even as late as the 1630s, when other nations were already regularly trading there, foreign writers took the time to mock such assertions. As the Welsh-born merchant Lewes Roberts put it, the Portuguese “brag of the conquest of the whole country, which they are in no more possibility entirely to conquer and possess, than the French were to subdue Spain when they possessed of the fort of Perpignan, or the English to be masters of France when they were only sovereigns of Calais.” Quite.

[…]

But for all their tardiness, the Dutch arrival in the Indian Ocean was dramatic. The English may have been the first to threaten the Portuguese monopoly, but in the whole of the 1590s they sent a mere two expeditions out east, and in 1600-10 sent only a further eight (seven by the newly-chartered East India Company (EIC), with a monopoly over English trade with the region, and another voyage licensed to break that monopoly in 1604 by the king, which unhelpfully spoiled the company’s relations with local rulers by turning pirate and plundering Indian and Chinese ships). What the English sent out over the course of twenty years, the Dutch exceeded in just five. Between just 1598 and 1603, after the successful return of de Houtman’s first voyage, they sent out a whopping thirteen fleets — and this despite their merchants not even pooling their efforts like the English had until the very end of that period, when in 1602 the various small and city-based Dutch companies were merged to form a single, national joint-stock monopoly, the Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC). The founding of the VOC accelerated the divergence. Between 1613 and 1622 the EIC sent out a paltry 82 ships compared to the VOC’s 201.

The sheer quantity of Dutch ships heading for the Indian Ocean meant that they were soon dominant amongst the European merchants there, capturing forts from the Portuguese, founding further bases of their own, and able to forcibly keep the English out — sometimes by attacking the English directly, other times by simply threatening any of their would-be trading partners. The steady stream of Dutch ships also allowed them to resupply and maintain their factors — the key infrastructure of long-distance commerce, as I explained in last week’s post for subscribers. They were able to have a presence, and project force, in a way that the English could not. By 1638, Lewes Roberts, despite often lauding England’s commercial achievements, and being an EIC official himself, had to concede that in the Indian Ocean “the English nation are the last and least”.

That English weakness was reflected in how EIC merchants had to comport themselves in the region so as to have any share in the trade at all. Despite the EIC’s later reputation for bloodthirsty rapaciousness, in the early seventeenth century they were highly reliant on good relations with the locals. Whereas the Dutch could often afford to use force and bear the repercussions, the English more or less only held on in the early days by ingratiating themselves with local rulers — often by finding common cause against the aggressive and domineering Dutch. The infrequently-supplied English factors were often heavily indebted to local merchants too, including the Indo-Portuguese — a group that they often married into, for access to social networks and support. As the historian David Veevers argues in a new overview of the early EIC (a relatively pricey academic book, but compellingly argued and juicy with detail), the English often went further than just friendliness or integration, subordinating themselves to local rulers too. Of the few early forts that the English managed to establish, for example, that at Madras in 1640 was only built because the local ruler encouraged it, treating the English there as his vassals.

July 20, 2021

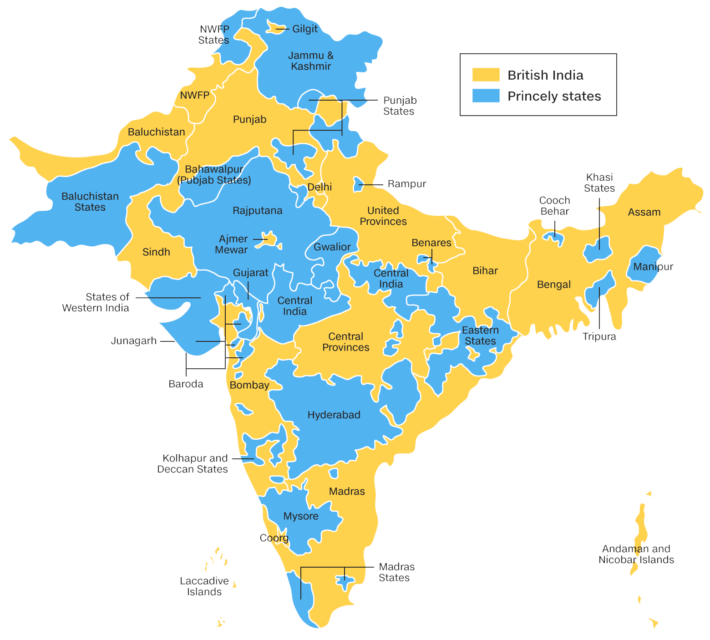

An unlikely survivor in India, His Highness the Prince of Arcot

Ned Donovan explains why there is still a Prince of Arcot, despite the Indian government having abolished all the titles and privileges of the nearly 600 “Maharajas, Maharanas, Rajas, Nawabs, Khans and so on” of the Princely states that were incorporated into modern India after Partition in 1947:

A significant amount of effort was taken during the process of independence to integrate these princely states into the newly independent countries. Almost all of the rulers acceded quickly and peacefully in return for recognition of their symbolic status and titles by the new republics who also promised perpetual large annual payments to sweeten the deal. A handful of princely states were stubborn and were integrated by force, with issues as a result to this day, such as Jammu and Kashmir.

As a result, for the first few decades of independent India, there existed a class of royals recognised within the republic, with privileges and financial support not that different to what they received during the period of British rule. But in 1971 this came tumbling down.

The then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi amended the Indian Constitution to abolish all privileges and titles, along with any financial subsidies. She believed the whole system to be at odds with the secular socialist republic she was attempting to perfect. The move also had financial benefits: the large princely subsidies stopped being a drain on the Indian treasury while much of the royals’ gold and property were seized by the Government in the process. In 1972, Pakistan followed suit and similarly abolished its remaining princes’ titles.

But the title “Prince of Arcot” somehow escaped to carry on to the modern day … thanks to an unusual historical situation and the presentation of letters patent from Queen Victoria:

In 1855, the 13th Nawab of Arcot died without children. The British, influenced by the East India Company, declared the kingdom had lapsed as a result and annexed it entirely. As a token compensation, Queen Victoria in 1870 gave the last Nawab’s uncle a pension and the title of “His Highness the Prince of Arcot” for him and his descendants in perpetuity. This was granted in a type of royal charter, known as letters patent.

As there was no land still to rule, the Princes of Arcot existed in a strange realm of being kings without a kingdom but with significant influence and prestige. The title continued to pass down through the original holder’s family and they built a large palace, Amir Mahal, in Madras that became a centre of culture instead of one of government.

H/T to Colby Cosh for the link.

July 3, 2021

Who were the Mughals? Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire explained

Epimetheus

Published 20 Oct 2019Who were the Mughals? Rise and Fall of the Mughal Empire explained (Documentary)

The Mughal empire’s history from Babur to the fall in 1857.

This video and others like it are sponsored by my Patrons over on patreon.

https://www.patreon.com/Epimetheus1776