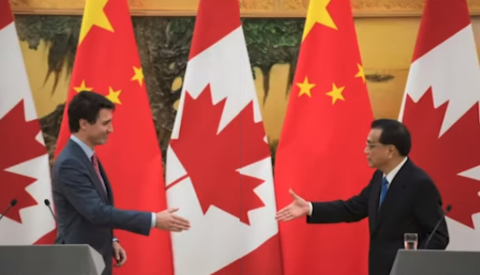

Like it or not, we’re already a few years into a new Cold War, this time with the Chinese Communist Party. The Canadian government seems to be among the last in the world to recognize this change in the geopolitical situation. In The Line, Andrew Potter shows why Justin Trudeau must stop trying to cuddle up to Xi:

The outrageous secret trials in China of Michael Spavor last Friday and Michael Kovrig this Monday are nothing more than punctuation marks on a storyline that has been obvious for some time now.

Which is why it was enormously gratifying to see more than two dozen diplomats show up to seek admittance to Kovrig’s trial. The fact that none was admitted is unfortunate but largely beside the point — what matters is the public display of solidarity. Even more gratifying perhaps is the announcement (by Canadian officials) that the U.S. has promised to treat the two Canadians as if they were American citizens. After all, it was our acquiescence to a U.S. request to arrest Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou at Vancouver International Airport in 2018 that prompted Beijing to nab Spavor and Kovrig in retaliation. While Chinese officials have denied that what this amounts to is hostage diplomacy, they’ve also made it clear that the fate of the Michaels is tied to that of Meng.

What makes the public support from all of these countries so remarkable is that a lot of them — the Czechs, the Finns, the Romanians — have very little to gain from sticking their neck out for Canada. More to the point, every one of these countries has good reason to wonder just how committed Canada itself is to this show of collective strength. After all, it was only five years ago that senior members of the Liberal party were freely — privately, but freely — saying that as far as the Liberal government was concerned, the U.S. was yesterday’s news and China was the horse Canada was going to ride into the future.

And while a lot has changed over the last five years (not least of which is the fact that Donald Trump has come and gone as president of the United States), it remains incomprehensible that it was just last year the Canadian National Research Council placed its disastrous COVID-19 vaccine bet with CanSino Biologics, a Chinese company with close ties to the Chinese military. What are our allies to make of the fact that only last month, the federal granting agency NSERC partnered with Huawei to sponsor computer engineering at Canadian universities. Or that Canada’s visa office in Beijing is owned and staffed by a Chinese police force?

Whether it is a matter of naïveté, bad faith, or outright cravenness, Canada continues to give every indication that it is a country that is still hedging its bets.