If your initial reaction to the headline is to assume this is because of the amazingly unsettled history of mainland China over the last several hundred years and the totally understandable fear of famines, I’m with you, but we’d both be wrong, as John Psmith explains:

One sunny December morning years ago, Jane and I were on holiday in the South of China. Far from the city, a little temple had been hewn out of a seaside grotto so that it partially flooded when the tide came in. We stood inside and gazed up at a statue of 觀音, “Guan Yin”, the lady to whom the temple was dedicated. Her legend originated in India, where she was known as the bodhisattva Avalokitasvara, but she’d been absorbed and appropriated by Chinese folk religion many centuries ago, and in this statue there was no trace to be found of her South Asian origins. A minute or two into our reverie, a local came over to us and, seeing that we looked out of place, helpfully explained in unaccented English, “This is one of the most important Christian goddesses.”

The Chinese are almost as bad as the Romans were about pilfering the deities of their neighbors, so you really can’t blame them when they occasionally get confused about who they stole them from. As with goddesses, so with food: earlier that day a different helpful local had steered us towards a restaurant specializing in “Western cuisine”. The menu listed steaks “French style”, “German style”, and “Barbecue style”. Soup options included minestrone and borscht, both of them with the surprise addition of prawns. Their pride and joy, however, was their breakfast menu which included roughly seventy different varieties of toast. The chef told me that there were restaurants in Europe and America that did not have so many kinds of toast, and beamed with pride when I nodded gravely. One of the diners, delighted to see real living and breathing Westerners in her local Western restaurant, told me: “The thing I love about this place is that it’s so authentic.”

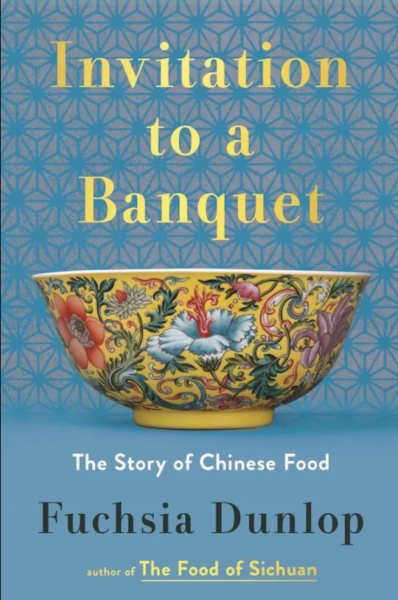

This “Western” restaurant may sound ridiculous to you, but it’s only as ridiculous as most of the “Chinese” restaurants you’ve encountered in the West. First of all, there’s no such thing as “Chinese” food. China is a country, but it’s the size of a continent, and it boasts a culinary diversity which exceeds that of many actual continents. Second, the dishes you encounter in the average Chinese restaurant over here bear about as much resemblance to real Chinese food as the seventy varieties of toast and the barbecue steaks do to French cuisine. “American Chinese food” is an interesting topic in its own right, and there are some good books about it, but now that I’m through the mandatory throat-clearing you have to do when writing about Chinese cuisine for a Western audience, I’m never going to mention it again.

China is a food-obsessed society. People are always talking about their next meal. People talk about it incessantly. The Chinese equivalent of talking about the weather, a way of making polite chitchat with strangers, is to mention a restaurant that you like, or a meal that you’re looking forward to. A standard way of saying “hello” in Mandarin is “你吃饭了吗?” In Cantonese it’s “你食咗飯未呀?” Both of them literally translate as something like “have you eaten yet?” and produce a natural conversational opening to begin immediately discussing food. Perhaps most uncanny to foreigners, Chinese people will sometimes discuss their next meal while they are in the middle of eating a fancy dinner. Dozens of gorgeous little dishes spread around them, chomping or slurping away at exquisite cuisine, and happily chattering about what they plan to eat tomorrow.

None of this is remotely new. If anything, between the Revolution and the famines, Chinese food culture is actually tamer than it used to be.1 We know this from literary and historical accounts, from archeological evidence (China had fancy restaurants about a thousand years before France did), and from the structure of the language itself. They say the Eskimos have an improbable number of words for snow,2 but the Chinese actually do have a zillion words for obscure cooking techniques. What’s more, many of the words are completely different from region to region, which is hardly surprising since the food itself is bewilderingly different from one side of the country to the other.

How food-obsessed are the Chinese? One of the most priceless artifacts belonging to the imperial family, the one thing the fleeing Nationalists made sure to grab as communist artillery leveled Beijing, now the most highly-valued object in the National Palace Museum in Taipei is … The Meat-Shaped Stone.3 A single piece of jasper carved into a lifelike hunk of luscious pork belly, complete with crispy skin and layers of subcutaneous fat and meat. Feast your eyes upon it.

1. Ferran Adrià, the legendary chef of El Bulli, once said that Mao was the most consequential figure in the history of cooking because: “[Spain, France, Italy and California] are only competing for the top spot because Mao destroyed the pre-eminence of Chinese cooking by sending China’s chefs to work in the fields and factories. If he hadn’t done this, all the other countries and all the other chefs, myself included, would still be chasing the Chinese dragon.”

2. I once tried searching Google to find out whether Eskimos really have a lot of words for snow. The top results were all places like BuzzFeed and the Atlantic denouncing this as an outmoded racist stereotype … followed by a Wikipedia article patiently explaining that no it’s actually true.

3. The Meat-Shaped Stone is not some weird aberration. The runner-up most valuable items in the museum are a piece of jadeite carved to look like a cabbage and a very fancy cooking vessel.