My cynical concerns, to be sure, are not about Kondo herself. I assume that she is sincere in what she offers, and indeed I expect some might find her counsel truly useful. It is the nature of her attraction to Westerners that gives me pause. This registers most powerfully for me when I re-imagine what she offers in a distinctly American guise. Before I became a professor, I sometimes earned my keep as a maid. And this class-conscious part of me is more oppositional still where the fascinations of “tidying” are concerned.

In more fanciful moments, I think about decluttering the KonMari method itself, stripping it of the middle-class respectability its exoticism confers. In place of Kondo herself, I imagine a tired maid (maids are always tired) using her years of “tidying” to counsel a family on managing their too-abundant stuff. She appeals to her experience both in cleaning and in life – invoking, say, that time she had to downsize from a double-wide trailer to a single-wide. (Long before the “tiny house movement” – another pop-culture fascination for those suffocated by their own stuff – many people already lived in tiny homes, and these are called trailers.) My sage maid uses her organisational competency, hard-earned from years of picking up after others, and her long practice in the art of making do without the new or the shiny. Most of all, she is full of plain good sense. But what she will not promise, cannot promise, is that cleaning house will bring you contentment. Nor will she suggest that you discard belongings that don’t “spark joy”. And that really is the rub.

My wise maid will forgo soft talk of joy, and use instead a harder, plain-speaking language to assess all that stuff: does it still have use in it? Most of it probably does, and what does not was probably pretty useless to begin with. After all, usefulness is not the prime criterion for many people’s buying habits. But finding that you have a house overstuffed with things useful but never used would promise its own kind of wisdom. It won’t spark joy to see it, but then the quest to find joy in all that stuff was never a good strategy to begin with. This, too, is about everything all at once.

Amy Olberding, “Tidying up is not joyful but another misuse of Eastern ideas”, Aeon, 2019-02-18.

April 7, 2022

QotD: The KonMari message without Marie Kondo

March 13, 2019

Marie Kondo as a “Mr. Miyagi for the anxious, late-capitalist, consumerist age”

At Aeon, Amy Olberding is not impressed with the pseudo-philosophy of the Marie Kondo cult:

Inspired by an episode of Tidying Up with Marie Kondo on Netflix, I cleaned my dresser drawers this weekend. It was a generally satisfying way to shirk work duties (the reason I watched Netflix in the first place). Yet, despite my neater bureau, I find the popularity of Kondo’s ‘tidying’ unbearable. We are awash in stuff, and apparently so joyless that the promise of joy through house-cleaning appeals to us. The cultural fascination sparked by Kondo strikes me as deeply disordered.

As a scholar of East Asian philosophies, one pattern in the Kondo mania is all too familiar: the susceptibility of Americans to plain good sense if it can but be infused with a quasi-mystical ‘oriental’ aura. Kondo is, in several ways, a Mr Miyagi for the anxious, late-capitalist, consumerist age. Unlike the Karate Kid, we are bedevilled by our own belongings rather than by bullies – but just as Mr Miyagi could make waxing cars a way to find one’s strength and mettle, so too Marie Kondo can magically render folding T-shirts into a path toward personal contentment or even joy. The process by which mundane activities transmute into improved wellbeing is mysterious, but the mystery is much of the allure, part of what makes pedestrian wisdom palatable. Folding clothes as an organisational strategy is boring. But folding clothes as a mystically infused plan of life is alluring. It’s not about the clothes. It’s about everything, all at once.

Popular uses of East Asian philosophies often tend this way: toward making the circumscribed expansive, toward making small wisdoms carry water for all the wisdom. This is how the ancient military theorist Sun Tzu might end up guiding your retirement savings, coaching your kid’s football team, improving your marriage, or even raising your kids. Sun Tzu’s Art of War has been leveraged into self-help advice on all of these subjects and more. Superficially, and also for trained scholars of early Chinese military history, it might seem that Sun Tzu is in fact only really interested in managing violent conflict well. But at a deeper level – which is to say, at the level of what might be marketed to gullible Western consumers – he is actually addressing all of life’s mysteries. What reads like straightforward instruction on wartime espionage might yet have something to teach us about our children. To access this deeper meaning, we need to assume that ‘oriental’ wisdom is never about this or that, but always about everything. And importantly, at root, it is reassuring.

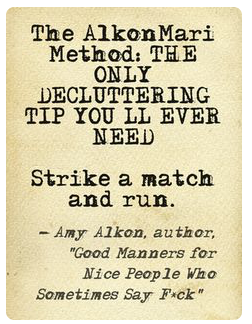

H/T to Amy Alkon, who offers her own take on tidying:

February 6, 2016

QotD: The addict’s political worldview

Writing about those rioters who in the summer of 2011 smashed, burned and looted shops across Britain, [Russell] Brand writes that their actions were no worse than the consumerism which he describes as having been “imposed” upon them. And this, I cannot help thinking, is an especially revealing phrase — entirely at one with a popular world view. That view sees “us” as poor victims of forces and temptations which are not only pushed upon us, but to which, when they are pushed upon us long enough, we will inevitably and necessarily succumb. If you are in a “consumerist” society long enough how could you be expected to just not buy crap you can’t afford when you don’t need it? No — the answer must be that of course you will succumb. And from there any bad behaviour — even looting and burning — will be excused because it will be someone else’s fault.

This is the world view of an addict. And the answer to all our society’s problems of the addict Brand is one answer which some addicts seek for their addiction — which is that everyone is to be blamed for their failings except themselves. Grand conspiracy theories and establishment plots offer great promise and comfort to such people. They suggest that when we fail or when we fall we do so never because of any conceivable failing or inability of our own, but because some bastard — any bastard — made us do it, has been planning to do it and perhaps always intended to do so. Of course the one thing missing in all this — the one thing that doesn’t appear in either of these books or in any of their conspiratorial and confused demagogic world view — is the only thing which has saved anyone in the past and the only thing which will save anybody in the future: not perfect societies, perfectly engineered economies and perfectly equal, flattened-out collective-based societies, but human agency alone.

Douglas Murray, “Don’t Listen to Britain’s Designer Demagogues”, Standpoint, 2015-01.

September 15, 2013

Back to school shopping fails to rescue the clothing chains

We all spent less than we were supposed to last quarter, and the clothing business is feeling tight:

Fantasies about a strong back-to-school shopping season had already gotten slammed when teen retailer American Eagle Outfitters, back in August, chopped its second-quarter earnings in half and confessed to lousy sales — down 2% overall and 7% on a comparable-store basis. CEO Robert Hanson blamed weak traffic and women who hadn’t bought enough of the stuff on the shelf. “The domestic retail environment remains challenging,” he concluded.

Competitor Abercrombie & Fitch reported its quarterly results the same day. While total sales were down “only” 1% year over year, booming international sales — up 15% overall and up 60% in China on a comparable store basis — papered over a debacle in the US, where sales plunged 8%. CEO Michael Jeffries summed up the US phenomenon: a “challenging environment,” “weaker traffic,” and “softness in the female business.” While “consumers in general” might be feeling better, he ventured, “that’s not the case for the young consumer.”

Alas, by today, his “consumers in general” had gotten the blues too, according to the University of Michigan/Thomson Reuters consumer-sentiment index. It plunged from 82.1 in August to 76.8 in September, the lowest since April. “Economists” on average had expected a flat 82 — they don’t get out much, do they? Particularly brutal was the collapse of the economic outlook index from 73.7 to 67.2, the lowest since January. So, a retail recovery in the second half? Maybe not so much.

March 15, 2013

Britain’s class system may have changed, but the snobbery is still all-pervasive

Tim Black reviews Consumed: How Shopping Fed the Class System, by Harry Wallop.

In short, class has stopped being the basis for a political identity; it has become a form of identity politics. As Wallop puts it: ‘Class is no longer what we do with our hands nine to five, it is what we do with our wallets at the weekend. How that money arrives in our wallets must play a part, but how we define ourselves and how others view us mostly comes down to the weekly drive to the local retail park, rather than the daily trudge to the factory.’

Consumed is a snarking and sniping attempt by Wallop, a consumer affairs writer at the Daily Telegraph, to anatomise these new consumerist class identities. At the upper end are the super-rich Portland Privateers, named after the private Portland Hospital in central London, where pregnancies come to fruition with the obligatory C-section at the cost of several grand and the toiletries are Molton Brown. Then in descending order come: the Rockabillies, defined by their love of a British holiday, ideally in the Cornish town of Rock; the Wood-Burning Stovers, who love a wood-burning stove almost as much as they love the Guardian; the Middleton Classes, who – like Carole Middleton, the Duchess of Cambridge’s mother – have vaulted up the social ladder, usually taking in a grammar school en route; the Sun Skittlers, a resolutely old-school working-class identity devolving upon reading the Sun, playing skittles, and earning enough to have bought one’s own home; the Asda Mums, who spend wisely, but take safety in big, well-known brands; and the Hyphen-Leighs, whose much sneered-at social aspiration is marked out by the unusually spelled double-barrelled names and the commitment to high-status brands, from Burberry to Paul’s Boutique. Other monikers crop up throughout, but these are the main ones.

If Consumed sounds rife with all forms of snobbery, from the inverse to the outright, that’s because it is. And this ought to be expected, too. In a society in which how you consume has been allowed to determine your identity, then snobbery, which was always a vice of the consuming class par excellence, the non-productive aristocracy, is bound to flourish. It allows groups to include initiates and to exclude the vulgar. Hence, as Wallop relentlessly details, the consumption choices of other people (and it is always other people) have now become objects of mockery and often condemnation.

[. . .]

As Wallop records, eating out in the 1950s was for many limited to Lyons Corner Houses or fish-and-chip shops. And it wasn’t just the high-cost of restaurants that deterred many; the arcane rituals of the hotel dining experience were equally off-putting. This is why, argues Wallop, the British embraced the classless, ritual-free environs of the fast-food joint, first in the form of Wimpy and latterly in the shape of McDonald’s or Burger King. ‘Of course, eating out in fast-food places, or indeed any places, never became a classless activity’, writes Wallop. ‘Classless merely became a euphemism for working class. No more so than with fast food, which over time took on a demonic quality, at least in the eyes of those who refused to eat it. Junk food for the junk classes.’

Junk food for the junk classes. In that one sentence, Wallop touches upon the crucial conflation of the object of consumption with those consuming. When Wood-Burning Stovers complain about McDonald’s, they are really complaining about the type of people that eat there.

March 12, 2013

If consumers were 10% better off … why did they call it a “disease”?

In Maclean’s, Stephen Gordon illustrates the classic case of burying the lede for popular economics:

So Dutch consumers are roughly 10% better off than they would have been, but companies have been able to compete only by paring their profit margins.

“The Dutch disease,” The Economist, November 26, 1977

Talk about burying the lede. That sentence appears at the end of the 10th paragraph of the much-referred-to but rarely read article in The Economist that coined the phrase “Dutch Disease.” In the normal course of things, a 10 per cent increase in consumers’ purchasing power would be the stuff of banner headlines, but, for some reason, The Economist chose to hide that point deep into the story and qualify it with a caveat about how hard it had become for companies to compete. (The answer to that, by the way, is: “So what if producers are struggling?” What really matters is consumer welfare.)

My take on the Dutch Disease debate can be summed up as follows: Why are we calling it a disease?

August 2, 2012

The real reason behind the war on the humble plastic bag

Tom Bailey explains that the reasons we’ve been given for the renewed attacks on plastic bags are not the real reason for the ongoing struggle:

Individually, a plastic bag weighs about eight grams. In total, we use about 10 billion of them a year, adding up to around 80,000 tonnes of plastic bags. A large number, perhaps, but not when compared with total municipal waste. The total amount of household waste produced each year is 29.6million tonnes. This means that plastic bags make up a mere 0.27 per cent of what we all throw away every year. This percentage would become even smaller if we were to include commercial and industrial waste in our calculations.

The total amount of oil used to produce plastic bags is also exaggerated, considering that most plastic bags are made using naphtha, a part of crude oil that isn’t used for much else and would probably be burnt away otherwise.

So what’s going on here? Why the panic about a simple little bag? The assault on plastic bags is really an assault on consumerism. There is a prevailing view among the green and mighty that consumerism is bad. It is portrayed as being a modern-day vice, devoid of meaning, something which atomises society, corrupting us through crude materialism and distracting us from more important issues.

Plastic bags are an outward reflection of the ease with which people can buy goods and take them home. People now have the disposable income to enter a shop unexpectedly and buy a load of stuff, and plastic bags mean they can rest assured they they will have the means to carry their purchases. How often do people returning home from work decide, on a whim, to make a quick stop at Tesco Express to buy a few items of food? How frequently, perhaps on a journey past Oxford Street, are we drawn into a sale by a piece of attractive clobber? Such nonchalant consumption would be made more difficult, perhaps more expensive, without shops’ provision of handy, free plastic bags.

I guess I must be a puppet of “Big Plastic”, as I’ve posted about this issue a few times already.

July 19, 2012

Choice: re-evaluating the notion that too much choice is a bad thing

There was a famous study several years ago that supposedly “proved” that providing too many choices to consumers was worse than providing fewer choices. At the time, I thought there must have been something wrong with the study.

The study used free jam samples in a supermarket, varying between offering 24 samples and only six, to test whether people were more likely to purchase the products (they were given a discount coupon in both variants). The result was that people who sampled from the smaller selection were more likely to actually buy the jam than those who had the wider selection to choose from. This was taken to prove that too many choices were a bad thing (and became a regular part of anti-consumer-choice advocacy campaigns).

Tim Harford explores more recent attempts to reproduce the study’s outcome:

But a more fundamental objection to the “choice is bad” thesis is that the psychological effect may not actually exist at all. It is hard to find much evidence that retailers are ferociously simplifying their offerings in an effort to boost sales. Starbucks boasts about its “87,000 drink combinations”; supermarkets are packed with options. This suggests that “choice demotivates” is not a universal human truth, but an effect that emerges under special circumstances.

Benjamin Scheibehenne, a psychologist at the University of Basel, was thinking along these lines when he decided (with Peter Todd and, later, Rainer Greifeneder) to design a range of experiments to figure out when choice demotivates, and when it does not.

But a curious thing happened almost immediately. They began by trying to replicate some classic experiments – such as the jam study, and a similar one with luxury chocolates. They couldn’t find any sign of the “choice is bad” effect. Neither the original Lepper-Iyengar experiments nor the new study appears to be at fault: the results are just different and we don’t know why.

After designing 10 different experiments in which participants were asked to make a choice, and finding very little evidence that variety caused any problems, Scheibehenne and his colleagues tried to assemble all the studies, published and unpublished, of the effect.

December 20, 2011

Next on the protest agenda: Occupy Xmas

Patrick Hayes talks about the new agenda item for the self-declared 99%:

At a time when Occupy protesters are closing up camps the world over — either due to force by the authorities or because it’s too cold to protest outside — the widely acknowledged founders of the Occupy movement, Vancouver-based magazine AdBusters has claimed protesters’ next move should be to ‘Occupy Christmas’. The rationale for this, is as follows: ‘You’ve been sleeping on the streets for two months pleading peacefully for a new spirit in economics. And just as your camps are raided, your eyes pepper-sprayed and your head’s knocked in, another group of people are preparing to camp-out. Only these people aren’t here to support Occupy Wall Street, they’re here to secure their spot in line for a Black Friday bargain at Super Target and Macy’s.’

What bastards the 99 per cent are! Occupy protesters have experienced an ordeal akin to Christ being nailed to the cross, and all the greedy, selfish, Judas-like masses want to do is shop! The new Occupy protests began on Black Friday (the day after Thanksgiving) in the US last month, where goods are heavily discounted in shops in an attempt to kick-start spending and get shops’ P&L sheets ‘into the black’ in the run-up to Christmas. Occupy protesters left their tents and headed to the malls to tell consumers — or ‘cum-sumer whores’ as some protesters put it in their leaflets — to stop buying Christmas presents at discounted prices for their loved ones.

The idea behind this, as AdBusters — renowned also for founding Buy Nothing Day — noted is that ‘Occupy gave the world a new way of thinking about the fat cats and financial pirates on Wall Street. Now let’s give them a new way of thinking about the holidays, about our own consumption habits… This year’s Black Friday will be the first campaign of the holiday season where we set the tone for a new type of holiday culminating with #OCCUPYXMAS.’

December 4, 2011

“Scratch a Walmart-basher and you’ll find a snotty elitist, a person who hates capitalism and consumption and deep down thinks the Wrong People have Too Much Stuff”

ESR shares his thoughts about WalMart bashing:

I find that, as little as I like excess and overconsumption, voicing that dislike gives power to people and political tendencies that I consider far more dangerous than overconsumption. I’d rather be surrounded by fat people who buy too much stuff than concede any ground at all to busybodies and would-be social engineers.

But there’s more than that going on here . . .

Rich people going on about the crassness of materialism, or spouting ecological pieties, often seem to me to me to be retailing a subtle form of competitive sabotage. “There, there, little peasant . . .” runs the not-so-hidden message “. . .it is more virtuous to have little than much, so be content with the scraps you have.” After which the speaker delivers a patronizing pat on the head and jets off to Aruba to hang with the other aristos at a conference on Sustainable Eco-Multiculturalism or something.

I do not — ever — want to be one of those people. And just by being a white, college-educated American from an upper-middle-class SES, I’m in a place where honking about overconsumption sounds even to myself altogether too much like crapping on the aspirations of poorer and browner people who have bupkis and quite reasonably want more than they have.

November 28, 2011

Megan McArdle reviews some recent scolding books on thrift

Megan McArdle admits right up front that she recently splurged on a very spendy kitchen appliance, so you know she does not number herself among the community of scolds on the topic of thrift:

For decades, Americans have wallowed in credit, shunned savings and delighted in debt. In 1982, the personal savings rate was 10.9% of disposable income, by 2005 it had fallen to just 1.5%. It has since rebounded, but remains a measly 5%.

All this profligacy supports a rather vibrant cottage industry in polemics against consumerism. Authors as varied as the economist Robert H. Frank (1999’s “Luxury Fever”) and the political theorist Benjamin R. Barber (2007’s “Consumed”) have ganged up on what they see as the particularly unequal and excessive American spending habits. Unsurprisingly considering their abhorrence of waste, they are avid recyclers; the same arguments, behavioral economics studies and anecdotes appear time and time again. Access to credit makes consumers overspend. Materialistic people are anxious and unhappy. The conspicuous-consumption arms race is unwinnable. Down with status competition! Down with long work weeks, grueling commutes and McMansions! Up with family time, reading and walkable neighborhoods! The effect is rather like strolling down the main tourist strip in a beach town: Each merchant rushes out of his shop, gesticulating wildly and showing you exactly the same thing that you saw at all the previous stores.

The latest person to open up shop on this boardwalk is Baylor marketing professor James A. Roberts. “Shiny Objects: Why We Spend Money We Don’t Have in Search of Happiness We Can’t Buy” runs mostly true to form, its main innovation being to add financial self-help advice to the usual lectures. The book includes not only exhortations but actual instructions—how to make a budget, get out of debt and save for retirement.

It’s a thorough survey of both academic research on consumerism and basic finance advice. Still, I first ran into an argument I hadn’t seen before somewhere around page 200 — that the perfect surfaces of modern products hasten the replacement cycle because they show wear so badly — and well before then Mr. Roberts had fallen into some of the terrible habits of the genre. Though less openly contemptuous of the spendthrift masses than many of his fellow scolds, he still exudes that particular sanctimonious anti-materialism so often found among modestly remunerated professors and journalists.

Here are some of the things that upset him and that “document our preoccupation with status consumption”: Lucky Jeans, bling, Hummers, iPhones, 52-inch plasma televisions, purebred lapdogs, McMansions, expensive rims for your tires, couture, Gulfstream jets and Abercrombie & Fitch. This is a fairly accurate list of the aspirational consumption patterns of a class of folks that my Upper West Side neighbors used to refer to as “these people,” usually while discussing their voting habits or taste in talk radio. As with most such books, considerably less space is devoted to the extravagant excesses of European travel, arts-enrichment programs or collecting first editions.

December 8, 2009

The downside to “ethical” shopping

There are some odd results of changing your shopping habits to be more environmentally conscious, says a recent study:

As the owner of several energy-efficient light bulbs and a recycled umbrella, I’m familiar with the critiques of “ethical consumption.” In some cases, it’s not clear that ostensibly green products are better for the environment. There’s also the risk that these lifestyle choices will make us complacent, sapping the drive to call senators and chain ourselves to coal plants. Tweaking your shopping list, the argument goes, is at best woefully insufficient and maybe even counterproductive.

But new research by Nina Mazar and Chen-Bo Zhong at the University of Toronto levels an even graver charge: that virtuous shopping can actually lead to immoral behavior. In their study (described in a paper now in press at Psychological Science), subjects who made simulated eco-friendly purchases ended up less likely to exhibit altruism in a laboratory game and more likely to cheat and steal.

[. . .]

It would be foolish to draw conclusions about the real world from just one paper and from such an artificial scenario. But the findings add to a growing body of research into a phenomenon known among social psychologists as “moral credentials” or “moral licensing.” Historically, psychologists viewed moral development as a steady progression toward more sophisticated decision-making. But an emerging school of thought stresses the capriciousness of moral responses. Several studies propose that the state of our self-image can directly influence our choices from moment to moment. When people have the chance to demonstrate their goodness, even in the most token of ways, they then feel free to relax their ethical standards.

H/T to Radley Balko for the link.

October 24, 2009

New cult

Lore Sjoberg has a new religion to offer:

There are many strange religions in this mixed-up, modern world — Discordianism, Pastafarianism, the Church of the Subgenius — but one of strangest and most popular is the Cult of the New.

People will pay more than twice as much to see a first-run movie compared to seeing it in a second-run theater or renting it and watching it at home. They’ll pay $50 for a videogame that will clearly be a $20 “greatest hits” game before too long.

They buy novels in hardback, comic books in their original run rather than waiting for the anthology. And then there are all those people paying $600 for video cards that, six months from now, will cost less than the shiny, full-bleed folding pamphlets currently being used to advertise the hardware.

It seems to me that the best way to instantly raise your standard of living is to live in the past. If you subsist entirely on two-year-old entertainment, and the corresponding two-year-old technology used to power it, you’re cutting your fun budget in half, freeing up that money for more exciting expenditures like parking meters and postage.