Unlike in Mongolia, where there were large numbers of wild horses available for capture, it seems that most Native Americans on the Plains were reliant on trade or horse-raiding (that is, stealing horses from their neighbors) to maintain good horse stocks initially. In the southern plains (particularly areas under the Comanches and Kiowas), the warm year-round temperature and relatively infrequent snowfall allowed those tribes to eventually raise large herds of their own horses for hunting and as a trade good. While Mongolian horses know to dig in the snow to get the grass underneath, western horses generally do not do this, meaning that they have to be stall-fed in the winter. Consequently in the northern plains, horses remained a valuable trade good and a frequently object of warfare. In both cases, horses were too valuable to be casually eating all of the time and instead Isenberg notes that guarding horses carefully against theft and raiding was one of the key and most time-demanding tasks of life for those tribes which had them.

So to be clear, the Great Plains Native Americans are not living off of their horses, they are using their horses to live off of the bison. The subsistence system isn’t horse based, but bison-based.

At the same time, as Isenberg (op. cit. 70ff) makes clear that this pure-hunting nomadism still existed in a narrow edge of subsistence. From his description, it is hard not to conclude that the margin or survival was quite a bit narrower than the Eurasian Steppe subsistence system and it is also clear that group-size and population density were quite a bit lower. It’s also not clear that this system was fully sustainable in the long run; Pekka Hämäläinen argues in The Comanche Empire (2008) that Comanche bison hunting was potentially already unsustainable in the very long term by the 1830s. It worked well enough in wet years, but an extended drought (which the Plains are subjected to every so often) could cause catastrophic decline in bison numbers, as seems to have happened the 1840s and 1850s. A sequence of such events might have created a receding wave phenomenon among bison numbers – recovering after each dry spell, but a little less each time. Isenberg (op. cit., 83ff) also hints at this, pointing out that once one factors for things like natural predators, illness and so on, estimates of Native American bison hunting look to come dangerously close to tipping over sustainability, although Isenberg does not offer an opinion as to if they did tip over that line. Remember: complete reliance on bison hunting was new, not a centuries tested form of subsistence – if there was an equilibrium to be reached, it had not yet been reached.

In any event, the arrival of commercial bison hunting along with increasing markets for bison goods drove the entire system into a tailspin much faster than the Plains population would have alone. Bison numbers begin to collapse in the 1860s, wrecking the entire system about a century and a half after it had started. I find myself wondering if, given a longer time frame to experiment and adapt the new horses to the Great Plains if Native American society on the plains would have increasingly resembled the pastoral societies of the Eurasian Steppe, perhaps even domesticating and herding bison (as is now sometimes done!) or other animals. In any event, the westward expansion of the United States did not leave time for that system to emerge.

Consequently, the Native Americans of the plains make a bad match for the Dothraki in a lot of ways. They don’t maintain population density of the necessary scale. Isenberg (op. cit., 59) presents a chart of this, to assess the impact of the 1780s smallpox epidemics, noting that even before the epidemic, most of the Plains Native American groups numbered in the single-digit thousands, with just a couple over 10,000 individuals. The largest, the Sioux at 20,000, far less than what we see on the Eurasian Steppe and also less than the 40,000 warriors – and presumably c. 120-150,000 individuals that implies – that Khal Drogo alone supposedly has [in Game of Thrones]. They haven’t had access to the horse for nearly as long or have access to the vast supply of them or live in a part of the world where there are simply large herds of wild horses available. They haven’t had long-term direct trade access to major settled cities and their market goods (which expresses itself particularly in relatively low access to metal products). It is also clear that the Dothraki Sea lacks large herds of animals for the Dothraki to hunt as the Native Americans could hunt bison; there are the rare large predators like the hrakkar, but that is it. Mostly importantly, the Plains Native American subsistence system was still sharply in flux and may not have been sustainable in the long term, whereas the Dothraki have been living as they do, apparently for many centuries.

Bret Devereaux, “That Dothraki Horde, Part II: Subsistence on the Hoof”, A Collection of Unmitigated Pedantry, 2020-12-11.

May 7, 2023

QotD: The long-term instability of bison hunting on the Great Plains

April 27, 2023

M1908 Mondragon Semiauto Rifle

Forgotten Weapons

Published 24 Nov 2014The M1908 Mondragon is widely acknowledged to have been the first self-loading rifle adopted as a standard infantry arm by a national military force. There are a couple of earlier designs used by military forces, but the Mondragon was the first really mass-produced example and deserves its place in firearms history.

Designed by Mexican general Manuel Mondragon (who had a number of other arms development successes under his belt by this time), the rifles were manufactured by SIG in Switzerland. They are very high quality guns, if a bit clunky in their handling.

The design used a long-action gas piston and a rotating bolt to lock. Interestingly, the bolt had two full sets of locking lugs; one at the front and one at the rear as well as two set of cams for the operating rod and bolt handle to rotate the bolt with. The standard rifle used a 10-round internal magazine fed by stripper clips, but they were also adapted for larger detachable magazines and drums.

Unfortunately, the rifle required relatively high-quality ammunition to function reliably, and Mexico’s domestic production was not up to par. This led to the rifles having many problems in Mexican service, and Mexico refused to pay for them after the first thousand of their 4,000-unit order arrived. The remaining guns were kept by SIG, and ultimately sold to Germany for use as aircraft observer weapons.

(more…)

April 10, 2023

US Army and Marine Corps deployments other than with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF)

Another excerpt from John Sayen’s Battalion: An Organizational Study of United States Infantry currently being serialized on Bruce Gudmundsson’s Tactical Notebook shows where US infantry units (US Army and USMC) were deployed aside from those assigned to Pershing’s AEF on the Western Front in France:

Apart from the war in Europe, the principal military concern of the Wilson administration during 1917-18 was the protection of resources and installations considered vital to the war effort. The threat of German sabotage in the United States was taken very seriously. In addition, Mexico was still unstable politically and sporadic border clashes continued to occur into 1919. Mexican oil was also regarded as an essential resource and the troops stationed on the Mexican border were prepared to invade in order to keep it flowing. However, all the National Guard, National Army, and even the Regular Army regiments raised for wartime only were reserved for duty with the AEF. (The National Army 332nd and 339th Regiments did deploy to Italy and North Russia, respectively, but both remained under AEF command.) This left non-AEF assignments in the hands of the pre-war Regular Army regiments.

Out of 38 Regular infantry regiments available in 1917, 25 were on guard duty within the Continental United States or on the Mexican border and 13 garrisoned U.S. possessions overseas. Local defense forces raised in Hawaii and the Philippines eventually freed the pre-war regiments stationed in those places for duty elsewhere. By the end of the war the 15th Infantry in China, the 33rd and 65th (Puerto Rican) Infantry in the Canal Zone, and the 27th and 31st Infantry (both under the AEF tables) in Siberia were the only non-AEF regiments still overseas. Inside the United States state militia (non-National Guard) units and 48 newly raised battalions of “United States Guards” (recruited from men physically disqualified for overseas service) had freed 20 regiments from stateside guard duties, but not in time for any of them to fight in France.

Only twelve pre-war regiments actually saw combat in the AEF. Nine of them served with the early-arriving 1st, 2nd, and 3rd AEF Divisions. The other three were with the late arriving 5th and 7th Divisions. One more reached France with the 8th Division, but only days ahead of the Armistice. By this time, the Regular Army regiments had long ago been stripped of most of their pre-war men to provide cadre for new units. They were refilled with so many draftees that their makeup scarcely differed from those of the National Army.*

The situation with the Marines was similar to that of the Regular Army. Most Marine regiments had to perform security and colonial policing duties that kept them away from the “real” war in France. Also like the Army, the Marines made Herculean efforts to accommodate a flood of recruits, acquiring training bases at Quantico Virginia and Parris Island South Carolina, as their existing facilities became too crowded. The Second Regiment (First Provisional Brigade) continued to police Haiti while the Third and Fourth Regiments (Second Provisional Brigade) did the same for the Dominican Republic. The First Regiment remained at Philadelphia as the core of the Advance Base Force (ABF) but its role soon became little more than that of a caretaker of ABF equipment.

Although there was little danger from the German High Seas Fleet ABF units might still be needed in the Caribbean to help secure the Panama Canal and a few other critical points against potential attacks by German surface raiders or heavily armed “U-cruisers.” Political unrest was endangering both the Cuban sugar crop and Mexican oil. To address such concerns, the Marines raised the Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Regiments as infantry units in August, October, and November 1917, respectively. The Seventh, with eight companies went to Guantanamo, Cuba, to protect American sugar interests. The Ninth Regiment (nine companies) and the headquarters of the Third Provisional Brigade followed. The Eighth Regiment with 10 companies, meanwhile, went to Fort Crockett near Galveston, Texas to be available to seize the Mexican oil fields with an amphibious landing, should the situation in Mexico get out of hand.

Three other rifle companies (possibly the ones missing from the Seventh and Ninth Regiments) occupied the Virgin Islands against possible raids by German submarines. In August 1918, the Seventh and Ninth Regiments expanded to 10 companies each. The situation in Cuba having subsided, the Marine garrison there was reduced to just the Seventh Regiment. The Ninth Regiment and the Third Brigade headquarters joined the Eighth at Fort Crockett.**

* Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War op cit pp. 310-314 and 1372-1379. A battalion of United States Guards was allowed 31 officers and 600 men. These units were recruited mainly from draftees physically disqualified for overseas service. The 27th and 31st Infantry when sent to Siberia were configured as AEF regiments, though they were never part of the AEF. Large numbers of men had to be drafted out of the 8th Division to build these two regiments up to AEF strength. This seriously disrupted the 8th Division’s organization.

** Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the World War op cit pp. 1372-78; Truman R. Strobridge, A Brief History of the Ninth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; revised version 1967) pp. 1-2; James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the Eighth Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; 1976) pp. 1-3; and James S. Santelli, A Brief History of the Seventh Marines (Washington DC, Historical Division HQ US Marine Corps; 1980) pp. 1-5.

April 5, 2023

Justin Trudeau chooses the Argentinian model over the Canadian model

In The Line, Matt Gurney considers the proposition that “Canada is broken”:

To the growing list of articles grappling with the issue of whether Canada is broken — and how it’s broken, if it is — we can add this one, by the Globe and Mail‘s Tony Keller. I can say with all sincerity that Keller’s is one of the better, more thoughtful examples in this expanding ouevre. Keller takes the issue seriously, which is more than can be said of some Canadian thought leaders, whose response to the question is often akin to the Bruce Ismay character from Titanic after being told the ship is doomed.

(Spoiler: it sank.)

But back to the Globe article. Specifically, Keller writes about how once upon a time, just over a century ago, Canada and Argentina seemed to be on about the same trajectory toward prosperity and stability. If anything, Argentina may have had the edge. Those with much grasp of 20th-century history will recall that that isn’t exactly how things panned out. I hope readers will indulge me a long quote from Keller’s piece, which summarizes the key points:

By the last third of the 20th century, [Argentina] had performed a rare feat: it had gone backward, from one of the most developed countries to what the International Monetary Fund now classifies as a developing country. Argentina’s economic output is today far below Canada’s, and consequently the average Argentinian’s income is far below that of the average Canadian.

Argentina was not flattened by a meteor or depopulated by a plague. It was not ground into rubble by warring armies. What happened to Argentina were bad choices, bad policies and bad government.

It made no difference that these were often politically popular. If anything, it made things worse since the bad decisions – from protectionism to resources wasted on misguided industrial policies to meddling in markets to control prices – were all the more difficult to unwind. Over time the mistakes added up, or rather subtracted down. It was like compound interest in reverse.

And this, Keller warns, might be Canada’s future. As for the claim made by Pierre Poilievre that “Canada is broken”, Keller says this: “It’s not quite right, but it isn’t entirely wrong.”

I disagree with Keller on that, but I suspect that’s because we define “broken” differently. We at The Line have tried to make this point before, and it’s worth repeating here: we think a lot of the pushback against the suggestion that Canada might be broken is because Canada is still prosperous, comfy, generally safe, and all the rest. Many, old enough to live in paid-off homes that are suddenly worth a fortune, may be enjoying the best years of their lives, at least financially speaking. Suggesting that this is “broken” sometimes seems absurd.

But it’s not: it’s possible we are broken but enjoying a lag period, spared from feeling the full effects of the breakdown by our accumulated wealth and social capital. The engines have stopped, so to speak, but we still have enough momentum to keep sailing for a bit. Put more bluntly, “broken” isn’t a synonym for “destroyed”. A country can still be prosperous and stable and also be broken — especially if it was prosperous and stable for long enough before it broke. The question then becomes how long the prosperity and stability will last. Canada is probably rich enough to get away with being broken for a good long while. What’s already in the pantry will keep us fed and happy for years to come.

But not indefinitely.

March 5, 2023

The clear drawbacks of depending too much on oral history

In The Line, Jen Gerson explains why you need to exercise caution when dealing with oral traditions:

Lac La Croix Indian Pony stallion – Mooke (Ojibway for – he comes forth), October 2008.

Photo by Llcips09 via Wikimedia Commons.

A BBC travel feature published several weeks ago had the hallmarks of a classic progressive narrative. It was the tale of the “endangered Ojibwe spirit horse; the breed, also known as the Lac La Croix Indian pony, is the only known indigenous horse breed in Canada.”

The spirit horse was reduced to near extinction by European settlers who treat these magical creatures, deemed “guides and teachers”, as a mere nuisance to be culled and eliminated in favour of more profitable animals like cattle, or so the telling goes. A native breed of a beloved animal struggling to survive in the face of voracious colonial settlers.

Someone call James Cameron.

Unless you know a little evolutionary history, that is. In which case, you will already be aware that this story is pure pseudoscientific hokum.

Look, no one likes to be disrespectful about sensitive matters where the legitimately oppressed and aggrieved claims of First Nations peoples are concerned. This is a nation that is struggling to come to terms with its own horrific colonial past. This process is taking on many forms: witness the applause granted to singer Jully Black, who recently amended the national anthem “our home on native land”. Or, perhaps, the calls by one NDP MP to combat residential school denialism by passing new laws on hate speech — which would make questioning certain narratives not only an act of heresy, but also a literal crime.

Listening to stories, and respecting lived experiences and oral histories Indigenous people at the core of Canadian history and identity has given a new credibility to the traditional knowledge of First Nations people in academia, media, and in society at large.

But the story of the Ojibwe spirit horse is a clear example of the limits of oral history.

The horses now roaming the plains of North America are not a native species. The horse did evolve on this continent before migrating to Asia and Europe. However, the North American breed is believed to have been extirpated about 10,000 years ago (or thereabouts) during a mass extinction event that wiped out almost all large land mammals.

There is some evidence that isolated pockets of a native horse breed may have survived in North America much later than this, but the horses roaming about today are descended from those that were brought from Europe after the 15th century.

Of course, science is always evolving, but the overwhelming bulk of genetic and archeological evidence to date supports this theory. The native North American horse is long, long gone. The bands of horses freely wandering the backcountry are not wild, but feral; they’re the product of escaped or abandoned horse stock of distant European origin.

March 4, 2023

Corruption? In Arizona? It’s more disturbing than you think

Elizabeth Nickson digs into the allegations of massive corruption in the state of Arizona:

Governor Katie Hobbs speaking with attendees at a Statehood Day ceremony in the Old Senate Chambers at the Arizona State Capitol building in Phoenix, Arizona on 14 February, 2023.

Photo by Gage Skidmore via Wikimedia Commons.

One always likes a unifying theory, particularly one that explicates a thorny mystery rigorously ignored by the super-culture, by which I mean the world that the educated and financially secure occupy.

For instance: why was the preponderance of evidence of election fraud ignored by the courts? How did corruption in city and county governments take hold? Why are desperate people flooding the borders unchecked? Why is human and child sex trafficking so prevalent and not stopped? Why are we permitting our fellow citizens to become human wrecks in open-air drug markets? Why are our biggest cities degrading? Why, in so many cities, is middle class housing out of reach for the middle class?

The answer may be because a significant number of elected and appointed officials have been bribed by cartels and other criminal enterprises like the CCP or Asian gangs, like the ones operating in Vancouver, Seattle and San Francisco. And they are bribed through single family housing, bidding up and up and up the price of real estate.

Late last week, an extraordinary hearing took place in the Arizona Senate, whiphanded by Liz Harris, the chair of the committee investigating election fraud in Arizona. Only Harris expected the last presentation, and it was given by a woman we have all met in the nether worlds of finance when we are re-mortgaging, insuring, reinsuring, or investing in a local enterprise.

She is competent, reductionist, modest, and honest to a fault. She knows the paperwork she slides in front of you for signature, willing to describe every phrase in exhaustive detail.

One of those invisible people upon whom the entire system relies.

Jacqueline Breger was a single mother who owns her own insurance company, has multiple degrees, in accounting, an MBA, and various other necessary finance-industry certifications. She works with her husband1, an investigative attorney named John Thaler.

The story she told had half of America transfixed. Her testimony was based on that of a whistleblower from the Sinaloa cartel given during an application for witness protection, and the subsequent acquisition of 120,000 court documents that prove the case.

Nobody could believe it. Even those who would benefit by it if it were true, didn’t believe it. In the dozen or so interviews that followed the testimony, questions were barked at her and her employer with no small measure of hostility. Rick Santelli of CNBC looked as if all his hair was standing on end.

It starts this way:

In 2006, members of the Sinaloan cartel were arrested, tried and convicted for money laundering through single family homes in Illinois, Iowa and Indiana.

In 2014, Berger’s partner, John Thaler was asked to review the Sinaloan cases in Illinois, Indiana and Iowa and investigate whether the cartel had moved its enterprise to Arizona. Currently, the couple are working with several States Attorneys, the Attorneys General of New Mexico and California, and members of the FBI.

So this is a theory that requires attention.

1. Thaler and Berger are married. Thaler’s ex-wife was the Sinaloan cartel member who requested witsec, and decanted the evidence which triggered the acquisition of the thousands of forged and fake documents. Much of the story is focused on the domestic drama, as if domestic drama were not a part of everyone’s life at one time or another. I am more interested in discovering the truth of the matter.

February 1, 2023

Surviving on Leather

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 31 Jan 2023

(more…)

January 26, 2023

Indigenous Weapons and Tactics of King Philip’s War

Atun-Shei Films

Published 20 Jan 2023Native American living historians Drew Shuptar-Rayvis and Dylan Smith help me explore the military history of King Philip’s War from the indigenous perspective.

(more…)

January 8, 2023

Caesar Salad and Satan’s Playground

The History Guy: History Deserves to Be Remembered

Published 7 Sep 2022The rare example of a food fad that has maintained its popularity, the tangy dressing on romaine lettuce salad has a history as rich as a coddled egg, involving multiple nations, a bevy of movie stars, an infamous American divorcee, a disputed origin story, and, prominently, alcohol. And, perhaps surprising to many, is unrelated to the notorious Roman dictator.

(more…)

December 10, 2022

United States Empire – The Spanish-American War

The Great War

Published 9 Dec 2022The Spanish-American War (fought in Cuba and the Philippines) kickstarted US global ambitions and expanded their influence far beyond the borders of the United States. At the same time the war marked the endpoint of the decline of Spain as a global power.

(more…)

November 22, 2022

The real story of the First Thanksgiving

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 15 Nov 2022

(more…)

November 21, 2022

City Minutes: Colonial America

Overly Sarcastic Productions

Published 22 Jul 2022Colonial-era North America was a busy place, so let’s take a quick look through some of the major players from the perspective of the lands & cities they inhabited.

SOURCES & Further Reading: Lectures from The Great Courses: “1759 Quebec – Battle For North America” from The Decisive Battles of World History by Gregory Aldrete, “The American Revolution” from Foundations of Western Civilization II by Robert Bucholz, “North American Peoples and Tribes” from Big History of Civilizations by Craig Benjamin, “The Iroquois and Algonquians Before Contact” from Ancient Civilizations of North America by Edwin Barnhart, “Iroquoia and Wendake in the 1600s”, “Indian-European Encounters 1700-1750”, “The Seven Years War in Indian Country” and “The American Revolution Through Native Eyes” from Native Peoples of North America by Daniel M. Cobb, Britannica articles “New York” & “Boston” https://www.britannica.com/place/New-… & https://www.britannica.com/place/Bost…

(more…)

November 17, 2022

A History of Tacos

Tasting History with Max Miller

Published 5 Jul 2022

(more…)

November 7, 2022

“We are the descendants of good team players”

Rob Henderson considers the Male-Warrior hypothesis:

The male-warrior hypothesis has two components:

- Within a same-sex human peer group, conflict between individuals is equally prevalent for both sexes, with overt physical conflict more common among males

- Males are more likely to reduce conflict within their group if they find themselves competing against an outgroup

The idea is that, compared with all-female groups, all-male groups will (on average) display an equal or greater amount of aggression and hostility toward one another. But when they are up against another group in a competitive situation, cooperation increases within male groups and remains the same among female groups.

Rivalries with other human groups in the ancestral environment in competition for resources and reproductive partners shaped human psychology to make distinctions between us and them. Mathematical modeling of human evolution suggests that human cooperation is a consequence of competition.

Humans who did not make this distinction — those who were unwilling to support their group to prevail against other groups — did not survive. We are the descendants of good team players.

It used to be accepted as a given that males were more aggressive toward one another than females. This is because researchers often used measures of overt aggression. For instance, researchers would observe kids at a playground and record the number of physical altercations that occurred and compare how they differed by sex. Unsurprisingly, boys push each other around and get into fights more than girls.

But when researchers expanded their definition of aggression to include verbal aggression and indirect aggression (rumor spreading, gossiping, ostracism, and friendship termination) they found that girls score higher on indirect aggression and no sex differences in verbal aggression.

The most common reasons people give for their most recent act of aggression are threats to social status and reputational concerns.

Intergroup conflict has been a fixture throughout human history. Anthropological and archaeological accounts indicate conflict, competition, antagonism, and aggression both within and between groups. But violence is at its most intense between groups.

A cross-cultural study of 31 hunter-gatherer societies found that 64 percent engaged in warfare once every 2 years.

Men are the primary participants in such conflicts. Human males across societies are responsible for 90 percent of the murders and make up about 80 percent of the victims.

The evolution of coalitional aggression has produced different psychological mechanisms in men and women.

Just as with direct versus indirect aggression, though, homicide might be easier to observe and track with men. When a man beats another man to death, it is clear what has happened. Female murder might be less visible and less traceable.

Here’s an example.

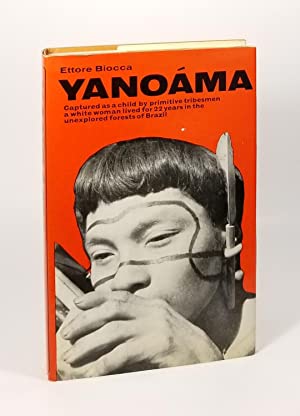

There’s a superb book called Yanoama: The Story of Helena Valero. It’s a biography of a Spanish girl abducted by the Kohorochiwetari, an indigenous Amazonian tribe. She recounts the frequent conflicts between different communities in the Amazon. After decades of living in various indigenous Amazonian communities, Valero manages to leave and describes her experiences to an Italian biologist, who published the book in 1965.

In the book, Helena Valero describes arriving in a new tribe. Some other girls were suspicious of her. One girl gives Valero a folded packet of leaves containing a foul-smelling substance. She tells Valero that it’s a snack, but that if she doesn’t like it she can give it to someone else. Valero finds the smell repulsive and sets it aside. Later, a small child picks up the leaf packet, takes a bite, and falls deathly ill. The child tells everyone that he got the leaf packet from Valero. The entire community accuses Valero of trying to poison the child, and banishes her from the tribe, with some firing arrows at her as she runs deep into the forest.

The girl who gave Valero the poisonous leaf packet formed a win-win strategy in her quest to eliminate her rival:

- Valero eats the leaf packet and dies

- Or she gives it to someone else who dies and she is blamed for it, followed by being ostracized or killed by the community

This is some high-level indirect aggression. Few men would ever think that far ahead (supervillains in movies notwithstanding). For most men, upon seeing a newcomer they view as a potential rival, they would just physically challenge him. Or kill him in his sleep or something, and that would be that.

Point is, this girl would have been responsible for Valero’s demise had she died. But no one would have known. If a man in the tribe, enraged at the death of the small child, had killed Valero, then he would be recorded as her killer. Or if Valero had been mauled by a jaguar while fleeing, then her death wouldn’t have been considered a murder.

Interestingly, the book implies that Valero was viewed as relatively attractive by the men, which likely means the girl who attempted to poison her was also relatively attractive (because she viewed her as a rival). Studies demonstrate that among adolescent girls, greater attractiveness is associated with greater use of aggressive tactics (both direct and indirect) against their rivals.

November 6, 2022

QotD: Thatcher and the Falklands

Mrs Thatcher saved her country — and then went on to save an enervated “free world”, and what was left of its credibility. The Falklands were an itsy bitsy colonial afterthought on the fringe of the map, costly to win and hold, easy to shrug off — as so much had already been shrugged off. After Vietnam, the Shah, Cuban troops in Africa, Communist annexation of real estate from Cambodia to Afghanistan to Grenada, nobody in Moscow or anywhere else expected a western nation to go to war and wage it to win. Jimmy Carter, a ditherer who belatedly dispatched the helicopters to Iran only to have them crash in the desert and sit by as cocky mullahs poked the corpses of US servicemen on TV, embodied the “leader of the free world” as a smiling eunuch. Why in 1983 should the toothless arthritic British lion prove any more formidable?

And, even when Mrs Thatcher won her victory, the civilizational cringe of the west was so strong that all the experts immediately urged her to throw it away and reward the Argentine junta for its aggression. “We were prepared to negotiate before” she responded, “but not now. We have lost a lot of blood, and it’s the best blood.” Or as a British sergeant said of the Falklands: “If they’re worth fighting for, then they must be worth keeping.”

Mrs Thatcher thought Britain was worth fighting for, at a time when everyone else assumed decline was inevitable. Some years ago, I found myself standing next to her at dusk in the window of a country house in England’s East Midlands, not far from where she grew up. We stared through the lead diamond mullions at a perfect scene of ancient rural tranquility — lawns, the “ha-ha” (an English horticultural innovation), and the fields and hedgerows beyond, looking much as it would have done half a millennium earlier. Mrs T asked me about my corner of New Hampshire (90 per cent wooded and semi-wilderness) and then said that what she loved about the English countryside was that man had improved on nature: “England’s green and pleasant land” looked better because the English had been there. For anyone with a sense of history’s sweep, the strike-ridden socialist basket case of the British Seventies was not an economic downturn but a stain on national honor.

A generation on, the Thatcher era seems more and more like a magnificent but temporary interlude in a great nation’s bizarre, remorseless self-dissolution. She was right and they were wrong, and because of that they will never forgive her. “I have been waiting for that witch to die for 30 years,” said Julian Styles, 58, who was laid off from his factory job in 1984, when he was 29. “Tonight is party time. I am drinking one drink for every year I’ve been out of work.” And when they call last orders and the final chorus of “Ding Dong! The Witch Is Dead” dies away, who then will he blame?

During the Falklands War, the Prime Minister quoted Shakespeare, from the closing words of King John:

And we shall shock them: naught shall make us rue,

If England to itself do rest but true.For eleven tumultuous years, Margaret Thatcher did shock them. But the deep corrosion of a nation is hard to reverse: England to itself rests anything but true.

Mark Steyn, “The Uncowardly Lioness”, SteynOnline.com, 2019-05-05.