An article at Strategy Page looks at the much-higher cost of modern weapons systems and compares a few modern items to their historical predecessors. An eye-opening example is the comparison of a battleship to a modern US Navy destroyer:

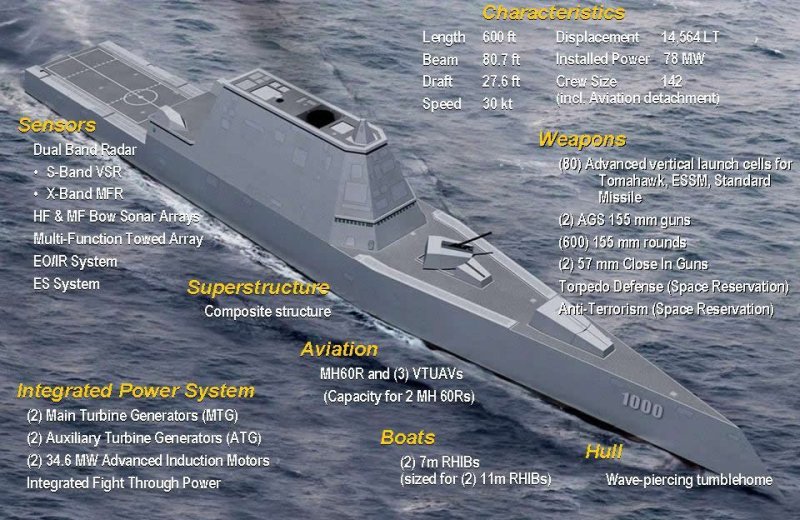

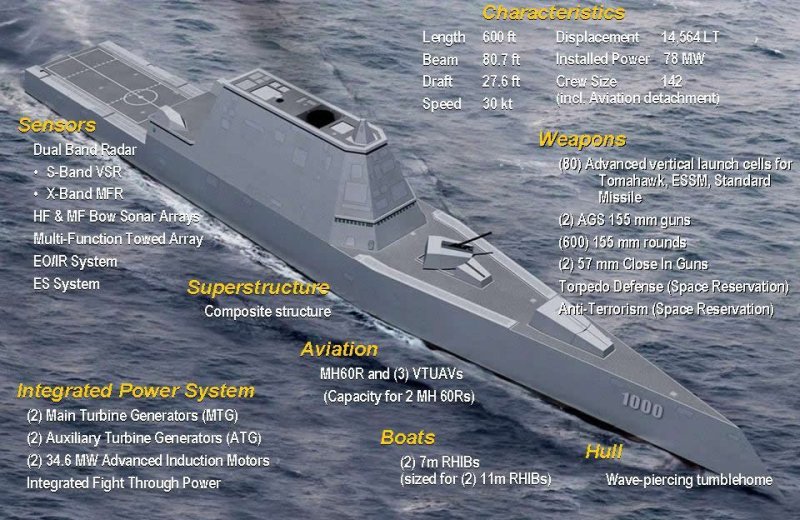

A new U.S. destroyer design, the DDG-1000, displaces 14,000 tons, is 193.5 meters (600 feet) long and 25.5 meters (79 feet) wide. A crew of 150 sailors operates a variety of weapons, including two 155mm guns, two 40mm automatic cannon for close in defense, 80 Vertical Launch Tubes (containing either anti-ship, cruise or anti-aircraft missiles), six torpedo tubes, a helicopter and three helicopter UAVs. The DDG-1000 was to cost $2 billion each, but it has been cut back to just three ships, which drives the cost up to $6 billion each.

A century ago, a Mississippi class battleship displaced 14,400 tons, was 123.2 meters (382 feet) long and 24.8 meters (77 feet) wide. Adjusted for inflation, it cost $150 million. A crew of 800 operated a variety of weapons, including four 12 inch (300mm), eight 8 inch (200mm), eight 7 inch (177mm), twelve 3 inch (76mm), twelve 47mm and four 37mm guns, plus four 7.62mm machine-guns. There were also four torpedo tubes. The Mississippi had a top speed of 31 kilometers an hour, versus 54 for DDG-1000. But the Mississippi had one thing DDG-1000 lacked, armor. Along the side there was a belt of 226mm (9 inch) armor and the main turrets had 300mm (12 inch) thick armor. The Mississippi had radio, but the DDG-1000 has radio, GPS, sonar, radar and electronic warfare equipment.

Each of the three DDG-1000’s being built cost 40 times more than the two Mississippi class battleships. Is the DDG-1000 40 times more effective? The DDG-1000 would make quick work of the Mississippi, spotting the slower battleship by radar or helicopter, and dispatching her with a few missiles. The Mississippi’s 12 inch guns had a maximum range of 18 kilometers, versus 130 kilometers for the Harpoon anti-ship missile. There has always been some debate if modern anti-ship missiles could really take down a battleship, what with all that armor and plenty of sailors for damage control work. The USS Mississippi ended its career in the Greek navy, and was sunk by German aircraft in 1941. Many battleships have been sunk, usually by bombs and torpedoes delivered by aircraft.

Although the last two American World War II era battleships were only sold off six years ago, battleship advocates keep coming with ways to revive these massive (45,000 ton) armored ships. The boldest proposals had most of the World War II era mechanical equipment and replaced with gas turbine engines and modern generators and electronics. This would reduce crew size from 2,700 to 600. But what really killed the battleship was the smart bomb, especially the GPS guided ones. The 16 inch battleship guns could not match this accuracy, unless a GPS guided shell were developed (a major cost). What really killed the battleship was massive innovation.

The DDG-1000 is still “pre” whatever the next dominant type of warship will be. But it’s ironic that a hundred years later, the descendent of the 14,000 ton Mississippi is a 14,000 ton surface ship that has more firepower, a longer reach and the ability to see targets hundreds of kilometers away, and is called a destroyer. And what kind of destroyers escorted the Mississippi? They were ships of under a thousand tons displacement, with crews of about a hundred sailors. Armed with a few 3 inch guns and some torpedoes, no one at the time expected them to evolve into a 14,000 ton warship.

USS Mississippi (BB-23), from the Wikipedia entry

Artist’s conception of the DDG-1000 class lead ship USS Zumwalt. Full-size image at Defence Industry Daily.